Vince McMahon is a monster.

Vince McMahon is a genius.

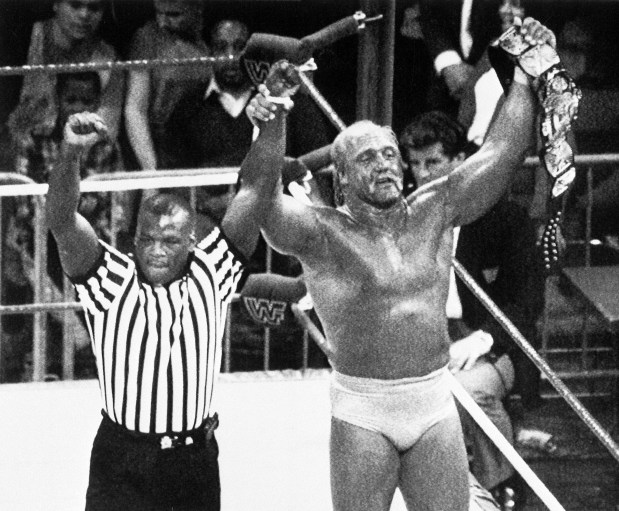

Vince McMahon is … What, you’ve never heard of him? That’s quite possible since he has spent his life and career in a realm apart from what some might consider polite society. But make no mistake. As the man who created the modern World Wrestling Entertainment and gave us a stable of sweaty stars (Hulk Hogan, real name Terry Gene Bollea), he did for wrestling what Ray Kroc did for hamburgers, turning what was a network of regional wrestling rivalries of fairly limited appeal into an arena-packing, money-printing enterprise.

He is the chatty centerpiece of a new six-part Netflix documentary series titled “Mr. McMahon,” named after the alter-ego character McMahon portrayed on-screen in the mid-’90s. Chatty that is, until he wasn’t. He was originally on board with this production, hence the many odd but interesting interviews you see. But when a former employee, Janel Grant, accused him of sex trafficking and filed a lawsuit against him, he clammed up for the filmmakers. He denied her accusations, saying the case was “replete with lies” and a “vindictive distortion of the truth.”

So, you won’t hear much about that case in the documentary, but previous allegations are discussed, as when we learn of WWE’s first female referee Rita Chatterton, who accused McMahon of rape. In this series he insists “that never happened” and it was “consensual” but we are told that he eventually withdrew his defamation lawsuit and paid her a multimillion-dollar settlement.

Legal troubles pepper the series. In another, the U.S. government (“big bullies,” McMahon says) took him to court on charges of illegal steroid distribution, a case in which he was found not guilty.

You’ll have to determine for yourself whether this is an honest portrait or, what McMahon now refers to as “misleading” or taking a “predictable path of conflating the ‘Mr. McMahon’ character with my true self, Vince.” Produced by Bill Simmons, the CEO of the sports and pop culture website The Ringer, and directed by “Tiger King” producer Chris Smith, it does a capable and often arresting job of exploring the many faces of Vince.

He was 12 years old before he met his father. Until then he lived a hardscrabble life with his mother and stepfather. He says that he suffered abuse at their hands, both physical and, as he alludes, sexual.

His ambitions were fueled when his father entered the picture. Vince McMahon Sr. was a big deal in the world of pro wrestling, but his area of clout was confined to the Northeast, part of a loose patchwork of territories kept within boundaries by a gentlemen’s agreement.

Vince wanted to wrestle but his dad said “No,” so he moved into commentating and announcing the matches. Eventually, he bought his father out, then avariciously began to move into other territories, defying other operators, stealing their wrestlers and staging events in their areas.

Those who are ardent wrestling fans will know many of these details but others, myself included, cannot help but be impressed by how shrewdly and quickly he was able to monopolize the wrestling business. He did so by creating bouts that were stories, painted in broad colorful strokes. Or, as McMahon put it, “Our business is no different than a play, a movie, books.”

Characters abound. In the 1980s, the Iran hostage crisis still fresh in minds, he fashioned battles between Hogan and a character called the Iron Sheik (real name Hossein Khosrow Ali Vaziri) to the delight of raucous and ever larger crowds.

And so did he create his answer to pro football’s Super Bowl with WrestleMania in 1985, which became an annual extravaganza. Look, there’s Aretha Franklin singing. There’s, of all people, artist Andy Warhol, yammering, “I’m speechless. It’s just so exciting, I don’t know what to say.”

We hear interviews with some of wrestling’s major stars, such as the aforementioned Hogan, The Rock, John Cena, the Undertaker and “Stone Cold” Steve Austin. We see and hear from McMahon’s family, all involved in his business: longtime wife Linda, business partner and politician, having once run for U.S Senate and named by former President Donald Trump to be the administrator of the Small Business Administration in his administration; daughter Stephanie and her husband Paul “Triple H” Levesque; son Shane, once a pro wrestler.

The series is fast-paced and peppered with scandals and betrayals, hostility and sexism (as one observer says, “We abused the hell out of women. They were like a toy for us”), a battle with Ted Turner’s rival wrestling operation and a very intriguing Bob Costas, the admired sportscaster who went from being a huge fan to almost suffering McMahon’s physical rage on TV. There are, as you can imagine, many who do not like or admire McMahon, including some passionate and tireless investigative reporters.

Given the troubles shadowing McMahon these days, this is likely to be the most honest and full portrait we will ever get. The 79-year-old billionaire has now retreated to the shadows. But there is no denying that he is an original, a self-manufactured creation only possible in the good old USA, for better and for worse.

As McMahon says: “I still haven’t quite figured out who I am.”

Clock’s ticking.

rkogan@chicagotribune.com