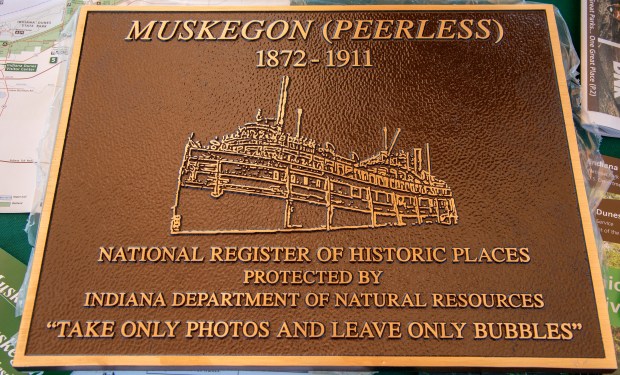

Indiana’s two shipwreck nature preserves have a lot in common. The Muskegon and the J.D. Marshall sank just a day apart.

The Muskegon’s site, about 1,000 feet north of Indiana Dunes National Park’s Mount Baldy, was officially dedicated Thursday afternoon during a program at the Old Lighthouse Museum in Michigan City as Indiana’s second shipwreck nature preserve in the Indiana waters of Lake Michigan.

Dignitaries had hoped to take a boat there but could only get close enough to see the site from a distance because the waves on Lake Michigan were three to five feet.

The Muskegon was destroyed by fire on Oct. 26, 1910, while docked at what is now Millennium Plaza, the site of the Old Lighthouse Museum and the former Smith Brothers cough drop factory.

The burned hulk sat moored at the site until the sand dredging equipment from the Muskegon was moved onto the J.D. Marshall, a sister ship owned by the same company.

Michigan City officials had the Muskegon removed from the pier and sunk offshore.

The very next day, on June 11, 1911, the J.D. Marshall was sunk near Indiana Dunes State Park in a storm. Four lives were lost in that shipwreck.

Charles Beeker, director of the Indiana University Center of Underwater Science, is one of the world’s top experts on historic shipwrecks. “This shipwreck’s been underwater since 1911, and being in freshwater there’s a lot of integrity left,” he said of the Muskegon.

Both the J.D. Marshall and the Muskegon sit in about 30 feet of water, making them easily accessible. “It’s a fantastic dive for beginning divers,” he said. “People want to see something that’s safe.”

At the Muskegon site, divers will be able to see ballrooms, the dining area and more. “It was the ship of the line for many, many years,” having been launched as the Peerless in 1872 as a passenger freighter, Beeker said. “It was one of the finest ships of its time.”

The Peerless was renamed the Muskegon at some point as the ship underwent a series of iterations, going from a grand passenger ship to a freighter to a timber ship to a sand dredge.

“The industrial revolution coincided with our settling around the Great Lakes, so you have this sail-to-steam transition,” said Sam Haskell, dive instructor and assistant director of the Center for Underwater Science. “From 1870 to 1950, technology progressed so fast that these boats just shifted in purpose. You have this Great Lakes passenger freighter that then became a gambling boat, then became a lumber trucker, that then became a sandsucker.”

“As both technology and the industries themselves that supplied the Midwest and the United States changed, the ships changed too. You see everything from sailing ships that they put steam engines on, steamships that they stripped stuff and just became barges that they towed,” Haskell said.

Sarah Muckerheide, of Greenfield, Indiana, is an IU student who participated in the Muskegon project. She’s hoping to earn her PhD in archaeology.

“I’ve been to both the Muskegon and the Marshall. It’s so exciting to see that antique steam power” and the giant boilers, she said.

“You can tell it’s been kind of mangled by the fire,” she said.

“The Great Lakes have such great preservation, even in shallow waters,” Muckerheide said. An estimated 50 shipwrecks have occurred in Indiana’s Lake Michigan waters, with 14 of them identified so far.

Divers have a long history of grabbing loose items. The designation as shipwreck nature preserves should stop that practice at the Muskegon and J.D. Marshall sites, she hopes.

Haskell said his team created slates for divers to use that have extensive information about the shipwrecks they’re visiting. The team installed a mooring system so boats could tie up without dropping an anchor and disturbing the site.

Indiana Department of Natural Resources Director Dan Bortner said he is excited to see the second shipwreck nature preserve dedicated. Bortner was one of Beeker’s students, calling the venerated professor “IU’s own Indiana Jones, I guess you can say.”

“Indiana is home to more than 300 nature preserves that protect our state’s natural places,” Bortner said, just two of them in Lake Michigan. “It will be protected for your lifetime, your children’s lifetime, and for generations of Hoosiers to come.”

Doug Ross is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.