By any objective measure, it was the single most impactful police shooting in Chicago in more than 40 years, and perhaps ever.

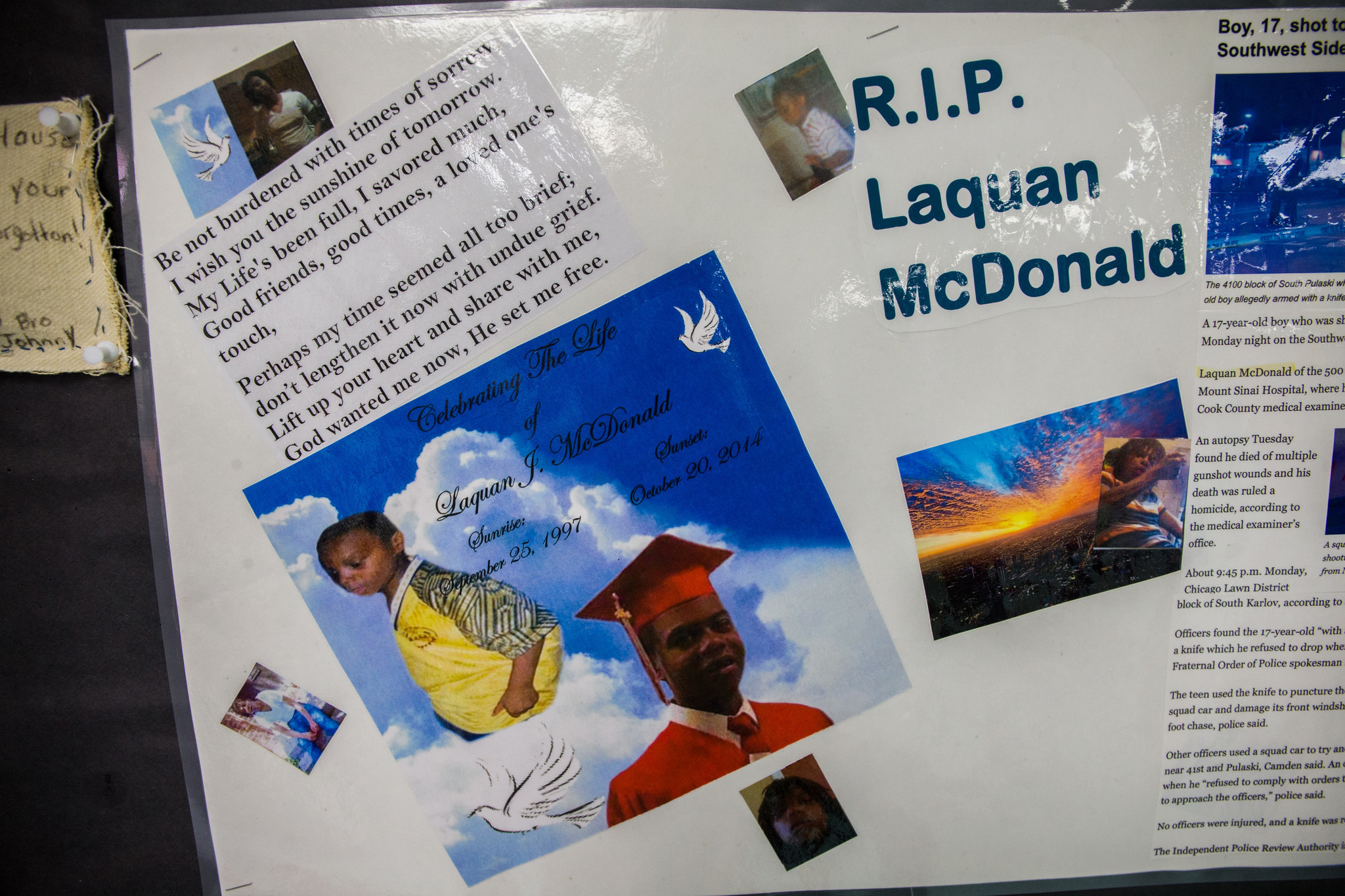

Ten years ago, on Oct. 20, 2014, a Chicago Police officer fired 16 bullets into 17-year-old Laquan McDonald. Chicago has not been the same since.

It was those 16 shots that forced an overt acknowledgment of longstanding, foundational problems within the Chicago Police Department — a “pattern or practice” of civil rights abuses and “the code of silence” — and led to wholesale changes within Chicago’s political and criminal justice power structure.

The shooting prompted an investigation into CPD by the Department of Justice. McDonald’s death effectively ushered in a new era of reform as it prompted a lawsuit against the city by the Illinois Attorney General’s Office, which led to the ongoing federal consent decree — a set of sweeping reform mandates that, a federal monitor has found, the CPD has so far struggled to comply with.

Frank Chapman, the executive director of the Chicago Alliance Against Racist Political Repression, had been fighting police brutality against Black Chicagoans for years before McDonald’s death. To Chapman, McDonald’s death “blew the lid off” the police brutality issue and became a touchstone moment.

“This struck me as a real, heinous crime, similar to what happened to Emmett Till,” in part sparking the Civil Rights Movement, he said. “16 shots. (McDonald) was out of commission after the first two shots.”

But the change many have pushed for in the decade afterward has not come quickly.

More than five years after the consent decree was entered, the city has reached compliance with 7% of its requirements, according to a court filing submitted last week by the independent monitoring team led by former federal prosecutor Maggie Hickey. Even with delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, that slow pace, Hickey said, flies in the face of the “guiding principles” that the reforms seek to demonstrate.

“The Parties negotiated ‘Guiding Principles’ that ‘provide the Court, the monitor, and the public with the context for . . . substantive requirements of [the Consent Decree] and the overall goals for each section,’” the independent monitoring team wrote last week. “These paragraphs provide significant insight into the intended outcomes of the Consent Decree and are essentially the “spirit” of the Consent Decree. With only 7% of paragraphs in Full compliance, however, it is not likely that either of the Parties would argue that these principles have been sufficiently demonstrated. The City will have to significantly increase its rate of compliance to reach full and effective compliance within eight years — a goal that was extended from five years due to COVID-19.”

Shooting rocked City Hall

The fallout from the shooting reverberated through Chicago’s halls of power.

Thirteen months after the shooting and just days after the shooting video was released, former Mayor Rahm Emanuel jettisoned his CPD superintendent, Garry McCarthy. Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez was beaten in the next primary election by Kim Foxx, herself now a lame-duck top prosecutor.

The now-former cop who killed McDonald, Jason Van Dyke, was the first CPD officer to face a murder charge for an on-duty shooting, and he spent three years in prison before his release in 2022.

Sensing his political vulnerability, former mayor Rahm Emanuel chose to not seek reelection. That bombshell opened the door for Lori Lightfoot and, now, Brandon Johnson.

Oct. 20, 2014

Van Dyke, then a 36-year-old patrol officer and 13-year CPD veteran, started his shift at 9 p.m. that day. He was assigned as a relief officer and was not working with his usual partner that night. Shortly after the shift began, the two drove to a 7-11 near 59th and Pulaski to get coffee. A few minutes later, the first call came in: someone was breaking into vehicles near 41st and Kildare, just west of Pulaski.

“I have a parking lot for trucks,” the 911 caller said. “I have a guy right here that is (stealing) the radios.”

McDonald had PCP in his system and was armed with a knife. As more officers responded, McDonald made his way to Pulaski, a busy north-south thoroughfare. The first officers gave McDonald distance, though he slashed the tire of a police vehicle and stabbed at its windshield as the cops tried to keep him on Pulaski. A Taser was requested, but not soon enough.

The teen was troubled. A ward of the state, his address was listed in West Humboldt Park, about five miles north of where the shooting occurred.

The city’s former corporation counsel, Stephen Patton, later told aldermen that McDonald had an “extensive juvenile record.” However, McDonald had recently enrolled at Sullivan Alternate School for troubled youth where he’d shown progress.

Van Dyke and his partner arrived near 41st and Pulaski just before 10 p.m., and Van Dyke fired the fateful 16 shots within seconds of exiting the squad car. McDonald was taken to Mt. Sinai Hospital where he was pronounced dead less than an hour later.

Earlier this week, a small wooden cross was nailed to a tree across the street from the Burger King at 41st and Pulaski. Someone tied a bouquet of pink fabric flowers to the trunk just beneath the cross.

Van Dyke maintained that McDonald put him in fear of his life, despite no other officers firing. The accompanying reports filled out and submitted after the shooting supported Van Dyke’s version of events.

The shooting was a relative blip on the radar for local or national media. Pat Camden, the former spokesman for the Fraternal Order of Police, told reporters that McDonald lunged at officers with the knife, a claim later disproven by the dashcam video.

“They killed my baby”

Rev. Martin Hunter, McDonald’s great uncle, is pastor of Grace Memorial Missionary Baptist Church in Lawndale.

He recalled sitting in his office with McDonald’s mother, Tina Hunter, just after McDonald was killed. He remembered Hunter sat in the chair across from the desk as they tried to understand what had happened.

“We were trying to sort it out, because this was absolutely unbelievable,” he said. “(Hunter) came here and she said, ‘Listen, they killed my baby.’”

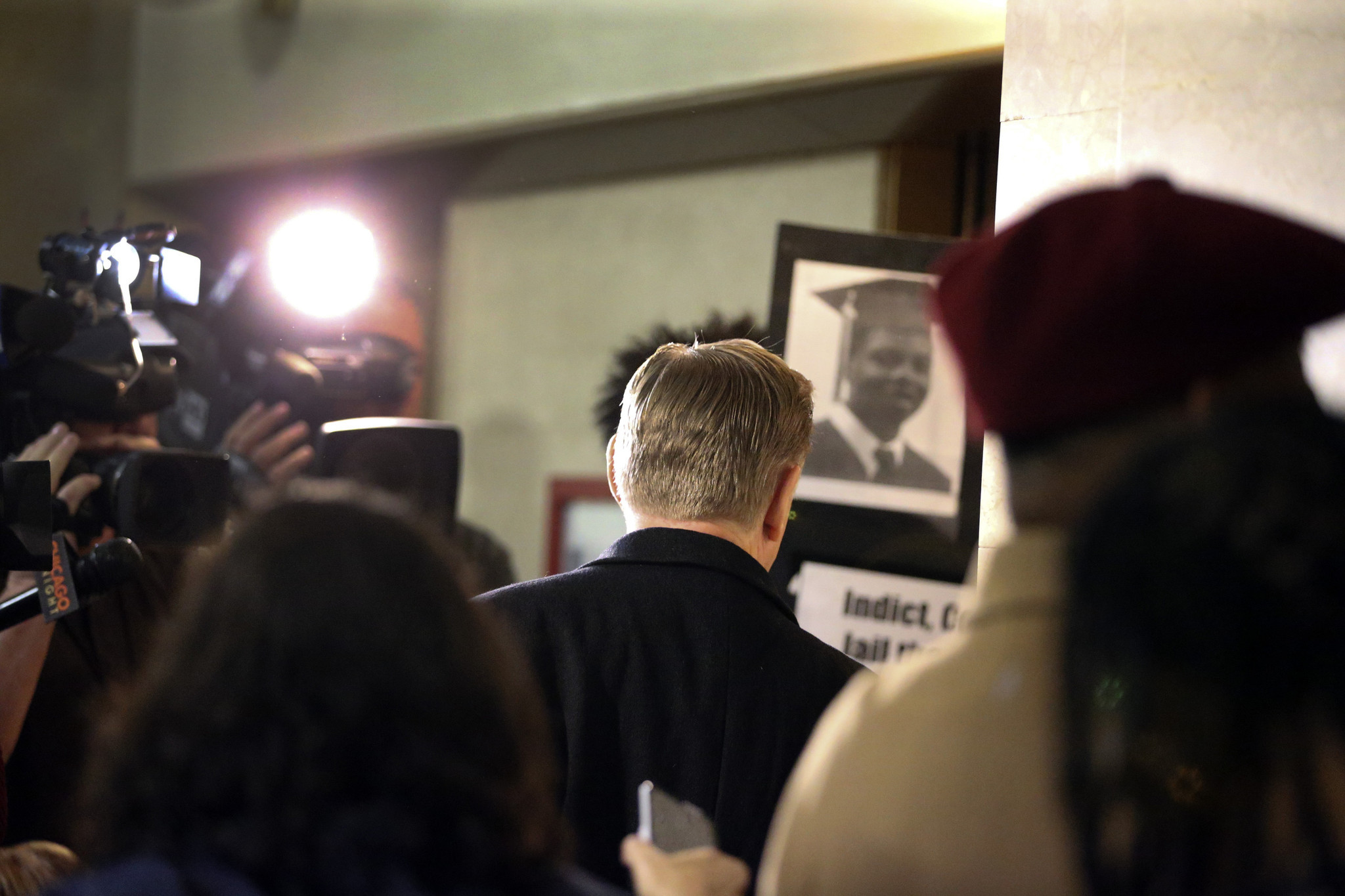

Hunter was the spokesperson for the teen’s family throughout the yearslong legal maelstrom that followed his death. His most vivid memory of the period before the videotape of the shooting was released was pushing back against “a media machine that began to villainize Laquan McDonald.”

“It felt like a war,” he said. “You were fighting a war, and you were defending yourself against an army that was bigger and more well financed than you.”

After the tape was released, Hunter said, one of his clearest memories was asking media outlets to stop playing it so much.

“How would you like to see your son die on TV every day?” he asked.

Hunter, who now has the Chicago Sun-Times front page from Van Dyke’s conviction framed in his office, said the legislative changes were “adequate as a first step.”

“It’s the first step to a million miles,” he said. “I’m happy that we are on our way now. I’m not happy that we’re there.”

Oversight, transparency & legacy

It was not until after McDonald’s death that the city and CPD move to outfit all patrol officers with bodyworn cameras. In cases of police shootings, it’s now policy for the Civilian Office of Police Accountability to release video and other documentation within weeks — a far cry from the pre-McDonald era.

COPA itself was a byproduct of the shooting, as the agency assumed the duties of the Independent Police Review Authority after the McDonald video was released in 2015.

COPA chief administrator Andrea Kersten said “transparency is the lasting legacy of the lessons that we learned from Laquan’s murder.”

“The very existence of this level of public discourse means that the public has access to more information than they had before,” Kersten said. “And yes, that leads to divergent viewpoints. Yes, that can lead to differing opinions, but at the end of the day we are tasked with making this information public because we as a city learned hard lessons about what happens when this very information is not made public.”

Kwame Raoul was sworn in as Illinois Attorney General in 2019, years after the shooting but in the infancy of the consent decree.

Raoul pointed to the frequent turnover at the top of CPD as a reason for the sluggish consent decree progress, though he’s encouraged by CPD superintendent Larry Snelling’s first year leading the department.

“I do believe that there’s current leadership in place within CPD that appreciates the value of the consent decree as a tool of improving the police department, improving their training, improving their policies and approach to policing that will engender better public trust,” Raoul said.

Chapman also attributed the eventual passage of the Empowering Communities for Public Safety ordinance, which created the city’s first-ever civilian police oversight body, in part to the organizing that erupted in response to McDonald’s murder. But, he added, there was more to do.

“We still don’t have accountability in Chicago like we need to have,” he said.

Attorney Dan Herbert represented Van Dyke in his criminal trial. The two men don’t speak often aside from holiday season well-wishes, but Herbert said Van Dyke has focused on maintaining his family since his release from prison in 2022.

“I think they’re just going along and just trying to make ends meet and raise their kids and working as hard as they can and keeping a low profile,” Herbert said of Van Dyke and his family.

A former CPD officer himself, Herbert said the effects of the McDonald shooting on the local criminal justice apparatus have been “enormous.”

“The police department, not just in Chicago but nationally, they have fundamentally changed the way they operate and the type of officer that they look for, really as a result of that case,” Herbert said. “It’s become a less aggressive, proactive police department in Chicago. The individuals that are being selected to join the police department in Chicago are very different. They’re being selected because they are less aggressive and less intimidating.”

Immediate aftermath

Within days of the shooting, members of the CPD command staff — including then-Deputy Chief Eddie Johnson, the CPD’s future superintendent — viewed the footage. In sworn testimony, a lieutenant who was present for the viewing said “There was never no question whether the shooting was justified.”

“Everyone agreed that Officer Van Dyke used the force necessary to eliminate the threat, and that’s pretty much it,” Lt. Osvaldo Valdez said in an interview with the city’s Office of Inspector General.

Van Dyke told investigators, “I think he’s going to try and take my life away from me.”

On Oct. 30, CPD Supt. Garry McCarthy stripped Van Dyke of his police powers and he was placed on desk duty.

Journalist Jamie Kalven soon filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office, seeking a copy of McDonald’s autopsy. In February 2015, Kalven authored a story for Slate that disclosed McDonald was shot 16 times and that the gunfire was captured on a CPD dashcam.

Two months later, in April 2015, the city council convened to approve a proposed $5 million settlement with McDonald’s family. The vote — approved without debate and before McDonald’s family filed any lawsuit — came about a week after Emanuel defeated mayoral challenger Jesus “Chuy” Garcia in a rare runoff election.

Attorneys for McDonald’s family initially demanded $16 million — $1 million per bullet. Before the vote, Patton, the city’s corporation counsel, told alders that federal and state investigators had launched criminal investigations into the shooting.

The settlement was approved, but dashcam video remained under wraps.

The next month, in May, journalist Brandon Smith filed a Freedom of Information Act request with CPD for a copy of the footage. After three extensions, CPD denied Smith’s request in August, citing an “ongoing investigation.”

Smith filed a lawsuit in Cook County Circuit Court challenging the denial. On Thursday, Nov. 19, 2015, Circuit Court Judge Franklin Valderrama — now a federal judge in Chicago — ordered that CPD release the video by the following Tuesday, Nov. 24.

City officials braced for impact. Emanuel convened a meeting with Black pastors and youth activists, urging peaceful demonstrations.

The video’s release would come only hours after Cook County prosecutors charged Van Dyke with murder and aggravated battery, 13 months after the shooting occurred.

At 5 p.m. on Nov. 24, Emanuel, McCarthy and other officials gathered for an especially well-attended press conference at CPD headquarters. They denounced Van Dyke, insisting he did not represent the Chicago Police Department, and again urged peaceful demonstrations. McCarthy said he felt he had the mayor’s full support going forward.

“The officer in this case took a young man’s life, and he’s going to have to account for his actions,” McCarthy said. “People have a right to be angry, people have a right to protest.”

Within minutes, the video was seemingly everywhere. It was as graphic as was rumored.

(new Image()).src = ‘https://capi.connatix.com/tr/si?token=bf001317-3a06-4c2f-ae9a-2acd831943b6&cid=38d5daa3-18ac-4ee1-a905-373c67622f25’;

cnx.cmd.push(function() {

cnx({

playerId: “bf001317-3a06-4c2f-ae9a-2acd831943b6”

, mediaId: “ff50be56-e037-4bda-a278-6a4c45a49c31”

}).render(“307d34eb437240948d9214020610122b”);

});

The footage showed the white officer open fire within six seconds of exiting his police SUV on South Pulaski Road as the Black teen walked diagonally away from officers with a small knife in his hand.

With McDonald about 10 feet away, Van Dyke took a step forward and fired. McDonald spun and fell to the street, lying motionless on his side. Van Dyke took another step forward and fired again. Over the next 13 seconds, he unloaded all 16 rounds from his gun, striking McDonald in the head, chest, back and both arms and legs.

Continued fallout

Weeks of protests and marches followed with a steady chorus of calls for Emanuel and McCarthy both to resign.

On Dec. 1, 2015, less than a week after the video was released, Emanuel called McCarthy to City Hall. The superintendent, who was making a series of morning news TV appearances at the time, was fired.

“At this point and this juncture for the city, given what we’re working on, he has become an issue rather than dealing with the issue, and a distraction,” Emanuel said of the firing.

McCarthy, later a mayoral candidate and now the chief of police in southwest suburban Willow Springs, has since characterized his firing as a political hit-job.

On Dec. 7, the United States Department of Justice announced a “pattern or practice” investigation into CPD. Two days later, Emanuel addressed the City Council with a speech that acknowledged a “code of silence” within the police department.

“The problem is sometimes referred to as the ‘Thin Blue Line.’ The problem is other times referred to as the ‘Code of Silence.’ It is this tendency to ignore; it is the tendency to deny; it is the tendency in some cases to cover-up the bad actions of a colleague or colleagues,” Emanuel said. “Permitting and protecting even the smallest acts of abuse by a tiny fraction of our officers leads to a culture where extreme acts of abuse are more likely, just like what happened to Laquan McDonald.”

The speech has remained a headache for city lawyers in the nine years since, as civil rights attorneys often cite those comments in various police misconduct lawsuits.

Moving forward

With a vacancy atop CPD after McCarthy’s ouster, the Chicago Police Board was tasked with nominating three finalists for the job to Emanuel. In the meantime, the department was led on an interim basis by John Escalante, a veteran CPD supervisor who was First Deputy Superintendent at the time.

Emanuel eventually selected Eddie Johnson — the CPD Chief of Patrol, who did not apply for the job — in March 2016. Johnson, another CPD lifer, grew up in Cabrini-Green and lived on the South Side for most of his life.

That same month, Kim Foxx, a protégé of Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle, defeated incumbent Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez in the Democratic primary.

The following year, in January 2017, the DOJ’s findings were made public.

“The Chicago Police Department (CPD) has engaged in a pattern or practice of unreasonable force – including deadly force – in violation of the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution,” the DOJ concluded after more than a year. “This pattern is largely attributable to systemic deficiencies in training and accountability, including a historical failure to train officers in de-escalation and failure to conduct meaningful investigations of uses of force.”

The shooting spawned another round of criminal charges in summer 2017. Three current and former officers who were at the scene when McDonald was shot — David March, Joseph Walsh and Thomas Gaffney — were charged with conspiracy, official misconduct and obstruction of justice connected with covering up the shooting. March was the lead detective and Walsh was Van Dyke’s partner on the night of the fatal shooting. All three were later acquitted.

In August, the Illinois Attorney General’s Office, led at the time by Lisa Madigan, filed a federal lawsuit against the city seeking a consent decree to enforce the reforms outlined in the DOJ report.

Negotiations between the city and state also sought to incorporate feedback from city residents regarding what they want in a police department. The judge overseeing the consent decree at the time — Robert M. Dow, now chief of staff to Chief Justice John Roberts — denied an effort by the Fraternal Order of Police to make the union a party in the consent decree lawsuit. Several community groups involved in the negotiations, though, previously joined the case as plaintiffs.

The parties entered a “memorandum of agreement” in March 2018. The following October, Van Dyke was found guilty of second-degree murder in McDonald’s death. Four other CPD officers, a sergeant among them, were fired from the department for covering up for Van Dyke the night of the shooting. Several high-ranking officers who were also at the scene later retired amid scrutiny.

The consent decree went into effect in early 2019, and Maggie Hickey and her monitoring team were soon selected to assess the city’s progress.

The monitoring team publishes two reports each year to grade CPD’s compliance, and the judge now overseeing the case, Rebecca Pallmeyer, holds regular status hearings that also include a lengthy public comment period.

The biannual reports are thorough and extensive, but the IMT has repeatedly noted its concerns about CPD’s progress, especially related to the police department’s policies on data retention and analysis. Those shortcomings, the IMT has said, threaten the viability of the reform efforts.

“In short, the City must improve its data systems to meet its burden of proof with the requirements of the Consent Decree,” the latest IMT assessment read. “And the Consent Decree will not end until the ‘Court finds that the City has achieved full and effective compliance with this Agreement and maintained such compliance for no less than two consecutive years.’”

“To even come close to reaching the existing eight-year expectation, the CPD will need to significantly increase its rate of Full compliance by the end of 2024.”