Draining the Kankakee Marsh came after decades of controversy and a spectacular failed attempt. Controversy over the effects continues today.

Michael Dobberstein, of Schererville, wrote the book on the history of the marsh that once drew sportsmen from around the world. His book, “Changing Landscapes in Indiana,” is set to come out in early 2026 from Purdue University Press.

“It might be definitive, but so far it’s the only one,” the retired Purdue University Northwest English professor said Tuesday, April 8, at a Kankakee Valley Historical Society event in Kouts.

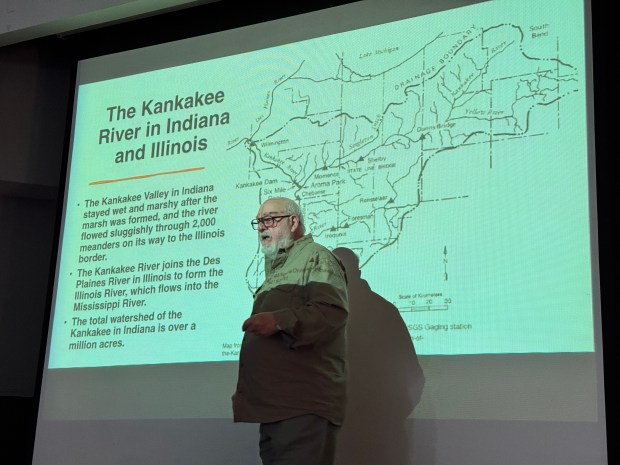

The Kankakee Marsh was created after the last ice age, around 13,000 years ago. The receding glacier left sandy soil along a laconic Kankakee River. Between St. Joseph County and the Illinois state line, there were some 2,000 meanders, he said. Paddling the river to Illinois from South Bend would have been a 250-mile trip 150 years ago, but after the river was straightened, it’s now about 80 miles.

As long as the Kankakee Marsh existed, people have lived in the area. Artifacts found at archaeological digs back up that assertion.

But in the early 1800s, the push to drain the swamp took hold. Rather than remaining a hunter’s paradise, many people wanted to turn it into farmland.

“That muck soil was really great at growing corn,” Dobberstein said. “In fact, that muck soil was some of the best in the country.”

In 1850, the federal government added fertilizer to this debate by passing the Swamp Land Act, giving swamps to the states. “Indiana took possession of over a million acres of wetland, just like that,” Dobberstein said. The Kankakee Marsh alone was 400,000 acres.

In 1855, the Indiana General Assembly rejected a bill to drain the swamp, but it became a model for all future plans, Dobberstein said.

A new drainage law was adopted in 1869, with only one dissenting vote, but residents hated the idea of a private company, Kankakee Valley Draining Co., putting a lien on their property to pay for the dredging. “If you didn’t pay it, they seize your land,” Dobberstein said.

A large outcry ensued, with over 2,000 lawsuits filed to fight the law, jamming Northwest Indiana courts. The law was repealed in 1872.

An 1875 law put control of draining the marsh into the hands of landowners, county commissioners and county courts. No private company would be able to seize private property to pay for the work.

Then came the 1883 plan to have the state help pay for draining the swamp. It was ambitious, yet misguided. Understanding it requires a short geology lesson.

In Indiana, the river bed was sandy. But starting in Momence, Illinois, the river bed is bedrock. Limestone.

The thinking at the time was that removing some of that limestone along a four-mile stretch in Illinois would drain the swamp, much like removing a limestone logjam.

“Can I really talk about this with a straight face?” Dobberstein wondered. “What are you going to do? Invade Illinois and blow it all up?”

After legal disputes over whether Indiana could take action in Illinois, Indiana finally gained access to the land on the condition that it go seven feet deep in shaving that four-mile stretch of limestone.

In 1893, workmen laid dynamite charges and started blowing them up. “It took them from August to December to do that,” an effort that cost Indiana $65,000 – the equivalent of roughly $2.3 million today, Dobberstein said.

Estimates at the time said about 2 feet of that rock layer was blasted away. A 1931 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report doubted even that much was removed. The effort was a flop.

In 1897, the Indiana Legislature washed its hands of the whole affair. “They spent $65,000 for some boondoggle of a thing” in Illinois but didn’t cause any actual drainage of the marsh. Additional work to drain the swamp would drain the state’s treasury.

Then came the Kankakee Valley Improvement Co., which proposed to drain the marsh using a government assessment on property along the route. “People fought it bitterly,” Dobberstein said, but after four years of legal battles, the company finally began its work. It took one year to dredge 10 miles, beginning in the South Bend area and working its way southwest toward Illinois.

“That big old shovel could scoop up 1,000 cubic yards of soil a day,” he said, as the company used equipment invented to create the Suez Canal.

“They did a really terrible job. They didn’t know what they were doing,” Dobberstein said. Sand piled up downstream, restricting the flow of the Yellow River into the Kankakee. So with water upstream now rushing downstream, flooding was occurring. That prompted landowners downstream to acquiesce to dredging and further channelization of the river.

By the time it was all done, the total cost was $1.2 million. “In 1923, $1.2 million was real money,” Dobberstein said. Today, that would be about $22.4 million.

What they got for that $3 per acre was some really productive farmland.

But they also got flooding problems.

“You can take some of the water out of the marsh, but you can never take the marshiness out of the marsh,” he said.

In 1927, a major flood occurred, the same year as the Mississippi River overflowed its banks.

“Guess who they want to fix this monumental problem? The government,” Dobberstein said.

In 1976, the estimated cost to partially restore the marsh to address flooding and other concerns was $124 million. Indiana balked, and neither Illinois nor landowners wanted it.

The Kankakee River Basin Commission was created in 1977, but it had no budget and no clear mission, Dobberstein said.

“The flood of 2018 brought some changes,” he said. The Indiana Legislature created the Kankakee River Basin and Yellow River Basin Development Commission to address the bureaucratic logjam. That commission created a 40-year plan, funded with money from landowners in each of the member counties in the watershed, and began work on alleviating flooding.

“This is not only much more modest, it’s more affordable,” Dobberstein said.

“You’re not going to fix it ever,” he said, but it’s improving.

Doug Ross is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.