She came to Orland Township to shake things up. She succeeded, establishing a legacy that has influenced thousands of south suburban kids.

Yet Dorothy Davis Turner was virtually unknown until late last year, when a small group of students at Andrew High School in Tinley Park and their teacher began a crusade to lift the name of a pioneering educator from the shadows of history.

Now the heart of stereotypical suburbia, an area packed with bustling malls and upscale subdivisions crisscrossed by busy arterial roads, Orland Park doesn’t much resemble itself from more than a hundred years ago, when small communities had sprouted along rail lines radiating from Chicago.

The region was decidedly rural in the 1910s, and most residents went about the business of farming. The bulk of their children were expected to be in that business too, once they got old enough. For one thing, there weren’t many other options for children beyond eighth grade.

Enter Dorothy Davis Turner, a 1917 graduate of the University of Chicago, who “was given the task of bringing secondary education to this area,” said Sheila Furey Sullivan, an English teacher at Andrew.

Before starting her second teaching stint in the district after taking some time off to raise her family, Sullivan learned about Turner’s role as the founder of what would become Orland Park-based Consolidated High School District 230 Turner was mentioned on the district’s website, but Sullivan wanted to learn more. She brought it up in her classes over the years, but it wasn’t until last year a group of seniors in her AP literature class were inspired to dive in.

It tied in with a larger theme the class was exploring about women and society, “and the ease with which their contributions are overlooked and obscured,” Sullivan said.

The class hatched a plan to get the school’s media center renamed in Turner’s honor.

“Originally we wanted a statue, but we found out statues are really expensive,” Sullivan said. “We didn’t have $80,000.”

Renaming the area once called the school’s library would be doable. But it wouldn’t be easy.

“We had to go through a lot of hoops to get that sign up,” Sullivan said. The group met with the superintendent, principal and board members and drafted plans and rationales for the renaming. “It felt like a lot for what really is just a sign.”

But the recognition represented by the sign was worth the work, she said. Her students felt the same, and continued working on the project well past their graduation last May.

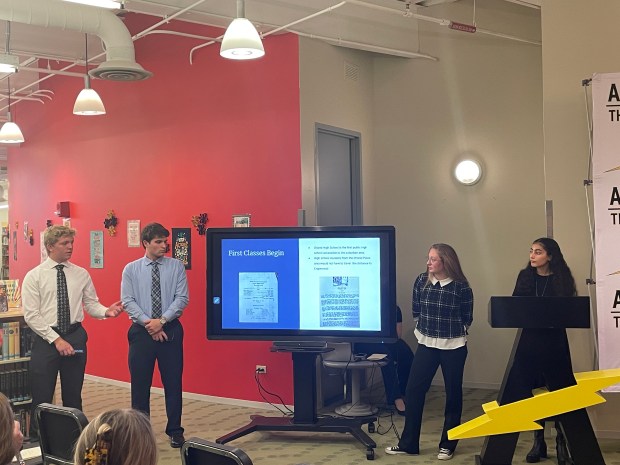

In November, the students reunited at Andrew for a ceremony unveiling the newly dubbed Dorothy Davis Turner Media Center.

Turner’s contributions went well beyond simply opening a high school.

“She faced lots of obstacles because it was such a rural area,” said Serena Naji, one of Sullivan’s 2023 literature students. “A lot of the residents were farmers and business owners, so they didn’t like to have their kids having to travel to go to school when they could be helping out with the farm. She also didn’t have a lot of resources and had to gather what she could.”

Among the documents the group unearthed was an undated account of the first year of Orland High School written by George H. Agate.

“During the summer of 1920, I remember something being said about a high school to be established in Orland,” Agate wrote. “This was uncertain because on the day after Labor Day, I entered Englewood High School” in Chicago.

By early October, he was among seven girls and six boys from Orland and Palos townships and Will County who gathered on the second floor of the one-and-a-half story Orland Park Village Hall.

“I became a student in the first class and was relieved to know Latin would not be taught,” Agate wrote.

To accommodate the new students, “two standard pit privies” were built out of pine boards outside. But students who sat on one side of the classroom’s long wooden table “had to bend a bit to get to their chairs because of the roof.”

Turner, then known as Miss Davis, was founder, principal and teacher, instructing the class in English, algebra, history and science. She also took students on field trips to Chicago and offered life lessons related to recent world events.

“We got some inkling of the devastation of war when she talked about her brother, a shell-shocked veteran of World War I,” Agate recalled.

For Sullivan and her students, the project helped paint a picture of a devoted educator who went out of her way to ensure kids had the opportunity to go to school.

“It sounds like she came from a comfortable background, too,” Sullivan said. “She didn’t necessarily have to do it, but it sounds like it was her belief system that it was the right thing to do.

She was convinced it was the right idea, the right thing that children should have access to secondary education. She knew she would face the dissenting opinions of the inhabitants of this area. It seemed like she had to be extremely determined, and had to do so with little resources.”

Beyond just having knowledge and the ability to impart it to her charges, she was able to connect with people young and old, Sullivan said.

“She was warm enough that the students connected with her and felt cared for by her,” Sullivan said. “She had all the skills — she politicked with the community to get the school going.”

As they learned more, Turner’s dedication and resolve became an inspiration to the researchers.

“(Turner) was quoted in an article that only she and the first 13 students would ever know how difficult their first year was,” Naji said. “She said there was a lot of criticism and prejudice toward their mission, but they continued on.”

Orland High School moved the following year to slightly better digs in a room inside the town’s bank. In 1922, the students finally had their own building, right after those initial students had graduated from the two-year program. The building is now part of Orland Park Elementary School on 143rd Street at the south end of Southwest Highway.

Turner spent about five years getting a high school off the ground in the Orland area before moving on to other educational pursuits. She eventually moved to Evanston, where she was a school board member for years.

Orland High School continued to grow through the 1930s and ’40s, when a gym was added in a Works Progress Administration project. Meanwhile, Orland Park retained its rural nature.

“There was poverty, racism and we had a town drunk,” a 1948 Orland High graduate told a Tribune reporter covering a 1994 reunion at the school.

It closed in 1954, replaced in the rapidly growing southwest suburbs by Carl Sandburg, A.A. Stagg and Victor Andrew high schools.

Though it’s in Tinley Park, Andrew’s media center is a fitting place to honor Davis, Naji said, because “it was the last school in our district to be founded and serves as kind of the pinnacle of her work.”

“It offers an understanding of how far we’ve come since 1920. Andrew stands as a sign of that dedication that she showed,” Naji said.

Now a freshman at University of Illinois in Champaign, Naji came back to Tinley Park for the renaming ceremony, which also was attended by Turner’s granddaughter and great-granddaughter, who traveled from out of state.

It’s a place that “embodies Turner’s values, and the way she educated,” Naji said.

It also is a place that showcased one small change from 124 years ago — the media center was where Naji had her senior year Latin class.

The ceremony in November was the “culmination of a year of effort,” Naji said. “It’s something I’m really proud of. It took a lot of work to get there, but it was a proud moment to do it in front of Dorothy Davis Turner’s descendants and our own families. It felt like we had done something meaningful.”

In a district where all the schools are named for men, the woman who started everything now has her name displayed large.

“It was important to me to make sure her story was told,” Sullivan said. “There are lots of times people do things that aren’t acknowledged — especially women. Mrs. Davis Turner is the embodiment of that. As an educator I’m proud of the tradition she established and we try to keep going.”

Landmarks is a weekly column by Paul Eisenberg exploring the people, places and things that have left an indelible mark on the Southland. He can be reached at peisenberg@tribpub.com.