President Donald Trump’s executive actions to attack diversity, equity and inclusion don’t have the force of law, University of South Carolina law professor Kevin Brown emphasized, so it’s been shocking to see the speed at which universities, nonprofits and even the business community have moved to end DEI initiatives.

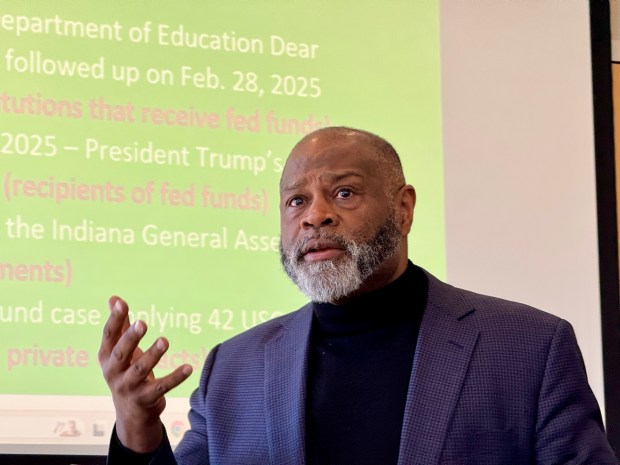

Brown spoke to a packed room at the Urban League of Northwest Indiana’s Diversity and Inclusion Symposium Thursday at Valparaiso University.

“We in the legal academy as well as the American Bar Association have really been stunned by the things that President Trump has done,” Brown said. “He is not a king. We do not have a king; we have a president. And if you were doing something that was legal before Jan. 20, the president can’t come and execute an executive order to make it illegal on Jan. 21.

“We’ve never really faced a president who has denied the rule of law to the extent that we’ve seen over the last six weeks,” he said.

Courts are slowly adjusting to executive orders, striking them down, Brown said.

“Simply put, the president can’t change the law. The president’s job is to enforce the law. Congress, the legislature, is the one that changes the law,” he said.

Brown offered a brief history of DEI initiatives and offered his opinion on major attacks as part of his threat assessment.

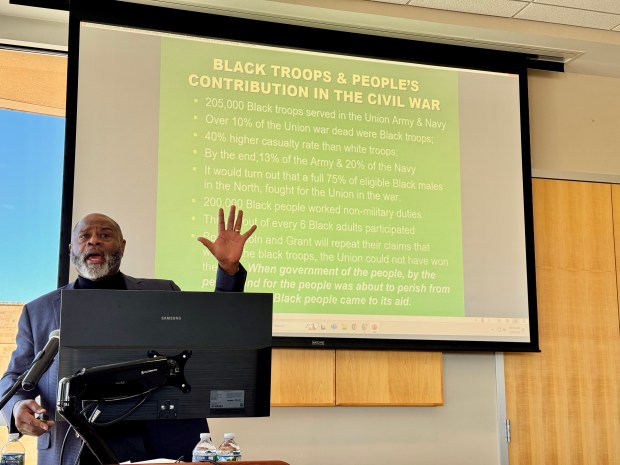

In the Civil War, the contribution of Black troops is overlooked, he said. There were 205,000 Black troops in the Union Army and Navy. More than 10% of the Union war dead were Black troops, with a casualty rate 40% higher than that of white troops.

About 75% of eligible Black men in the north fought for the Union, he added.

After the war, Congress passed a series of measures, including the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution, aimed at giving Blacks the same rights as whites.

Those actions are now being used in litigation aimed at bolstering white people’s claims that they deserve the same treatment as Blacks and other minorities and challenging Birthright citizenship.

A pivotal moment in attacks against DEI was the 1978 Regents of the University of California v. Bakke case. Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.’s opinion said race should be allowed among multiple factors in determining college admissions, but only to achieve the educational benefits from a diverse student body.

In his opinion, Powell said, “The clock of our liberties, however, cannot be turned back to 1868. It is far too late to argue that the guarantee of equal protection to all persons permits the recognition of special wards (Black people) entitled to a degree of protection greater than accorded others.”

A key outcome of the Bakke case was the new purpose of the equal protection clause was to protect the rights of individuals, not groups, Brown said.

“Justice Powell’s opinion is really the cause of the attacks on DEI today, so to a certain extent I’m saying this was baked in as early as 1978,” he said.

Brown singled out five major attacks on DEI, critical race theory, and affirmative action in the past two years.

In the 2023 Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University case, an affirmative action challenge, the Supreme Court said considering an applicant’s race as a factor for admissions is unconstitutional, overturning 60 years of legal precedent.

That ruling is relevant, Brown said, because the 1964 Civil Rights Act applied to not only governments but all recipients of federal funds.

A Feb. 14 “Dear Colleague” letter by the Department of Education purported to be an interpretation of the Harvard affirmative action decision and claimed some programs may appear neutral on their face but are, in fact, motivated by racial considerations, thus violating the law.

It was followed up by a second letter on Feb. 28 that retracted some of the claims of the original letter.

“If you actually took it that far, it would mean, of course, you couldn’t have Black student unions. You couldn’t have Black law student organizations. It would raise questions about Black studies programs. You would even have questions about historically Black colleges,” Brown said.

“Guess what else you couldn’t have? Celebrations for St. Patrick’s Day, because that’s for the Irish. You certainly couldn’t have Holocaust remembrance celebrations because that’s for a specific racial group. I think once they begin to realize this, they were like ‘OK, we don’t really mean that, so forget all that’,” he said, and that’s why the second letter was sent.

The Department of Education seemed to realize it’s prohibited by law from dealing with the content in school curricula, he said. That would violate First Amendment rights to free speech.

Anti-DEI executive orders issued Jan. 20 and Jan. 21 — Trump’s first and second days in office — were aimed at recipients of federal funds. Trump wanted to discourage DEI efforts by corporations and others.

“You can’t tell a private company what they can do with their own money so that was one of the reasons it was it was it was enjoined by the District Court,” Brown said. The other reason was that to ban DEI, it first has to be defined. Even DEI proponents have been struggling to define it, he said.

The biggest threat to DEI, Brown believes, is the Fearless Fund case. “This is the one that scares me the most,” Brown said.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866, which is now 42 USC 1981, is a very important civil rights program, but the Fearless Fund case has reinterpreted it, he said. That law says all people shall have the same rights as white people in regard to legal proceedings.

The Fearless Fund program offered $20,000 grants to black women entrepreneurs in information technology because they are so underrepresented. It was shut down in September in response to a legal challenge by the American Alliance for Equal Rights, which wanted to eliminate the restriction that recipients had to be Black women.

Under that rationale, law firms that had diversity scholarships limited to underrepresented minorities wouldn’t be allowed to restrict the qualifications to achieve the intended goal, Brown said.

Rather than advancing equality, attacks on DEI attempt to freeze the status quo for whites.

“Let me just remind you about the disparities,” Brown said. “Black family income is about 66% of nonwhite Hispanic income. Black poverty rates are about double that of white non-Hispanics.”

The unemployment rate for Black people is typically twice that of white people. For at least the last 40 to 50 years, the rate of home ownership for Blacks has been about 44% compared to 72% for whites.

Look at demographics for Americans 18 and under, and it’s clear the nation is changing. Whites in 2024 were 48.8% of that population, with Latino 25.9%, Blacks 13.8%, Asians 5.7%, and two or more races 5%.

Brown said the Supreme Court’s recent decisions pulling back from expanding DEI programs will have an effect on society.

He suggests Black students focus on entrepreneurship to be able to make more money than some of the fields they might study in college. “We’re going to see government significantly pulling back from DEI programs,” so more private organizations will need to fill in the gaps, he said.

Doug Ross is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.