You know who’s never had a big solo museum show in his own hometown?

Strange as this sounds: Theaster Gates, the renowned, longtime Chicago artist, sculptor, community developer, collector, painter and all-around renaissance man.

That’s why, beginning Sept. 23, the Smart Museum of Art (5550 S. Greenwood Ave.) at the University of Chicago in Hyde Park will open a landmark mid-career retrospective of Gates’ far-flung art practices, using most of the museum’s space, drawing on his paintings, pottery, films, installations and reclamation projects. “Theaster Gates: Unto Thee,” set to run through Feb. 22, 2026, will be the first large-scale attempt by a Chicago institution to place a traditional museum framework around a local artist best known for 20 years of non-traditional, not-always-gallery-obvious works. How, after all, can a gallery develop a retrospective of an artist whose acclaim often derives from the transformation of South Side communities?

Depending on the critic, Gates, 51, a professor of visual art at the University of Chicago, is a land artist. Or he occupies the social practice niche of the arts world. Or he’s an essayist revisiting little-known histories using salvaged materials. Or he’s just an ambitious archivist. ArtReview called Gates a “poster boy for socially engaged art.” England’s Tate Liverpool museum described him as no less than “one of the world’s most influential living artists.” Yet he’s not often shown in Chicago.

He began as a potter and has since created hundreds of installations, paintings and sculptures, but Gates is still best known for remaking a series of bungalows in the Dorchester neighborhood into sort-of living artworks, employing the reclaimed materials from those buildings and making room for local artists. He’s bought up the entire stock of a fading record store. He’s acted as preservationist for the last remnants of Johnson Publishing (the Chicago home of Ebony and Jet magazines). In 2015, he reopened a 1923 savings and loan as the Stony Island Arts Bank, a combination exhibition space, library, archive and home to the Rebuild Foundation, his group focused on using arts and culture to revitalize disinvested Chicago spaces.

In a quiet spot on Stony Island Avenue, beside the bank, is the gazebo in which 12-year-old Tamir Rice was killed by Cleveland police in 2014. Gates reclaimed that, too.

How, in other words, does a museum do justice to that inside gallery walls?

The Smart’s answer is by mingling Gates’ creations with his reclaimed projects, then expanding the exhibition into a number of the places developed by Gates, many of which are only blocks away from the institution. “A traditional museum show keeps most of its programming inside the museum,” said Smart Director Vanja Malloy. “But the experience of some of the places Theaster invested in is really only captured by going there.” Programming will sprawl to Stony Island and beyond; the opening reception will happen simultaneously at the Smart and Gates’ other spaces.

This is not, of course, Gates’ first substantial exhibition. Far from it. The Museum of Contemporary Art, in 2013, hosted a large installation by Gates of repurposed pews from Bond Chapel at the University of Chicago. He’s had major showings at the Venice Biennale, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and countless international galleries. A 2007 solo show at the Hyde Park Art Center focused on dozens of Gates’ clay plates.

“Unto Thee,” though, will showcase new paintings, sculptures and films, beside such reclamation works as Bond’s church pews, a chunk of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel, the personal library of University of Chicago Slavic language professor Robert Bird. Part of Gates’ practice has been repurposing artifacts and collections cast off by the university.

“People talk about the art world like it’s a monolith,” Gates said, “and maybe Chicago institutions just had a specific sense of who was important at various moments. Plus, I am from Chicago but my studies were in Iowa, at Harvard, in South Africa. And I didn’t go to art school. I was without a (museum) cohort in Chicago. People early in my career would ask what was there to buy? It was a badge of honor I led with ideas, though since those days, I’ve had a significant practice making objects. It just played out elsewhere. When I came home, I feel more like a nonprofit leader.”

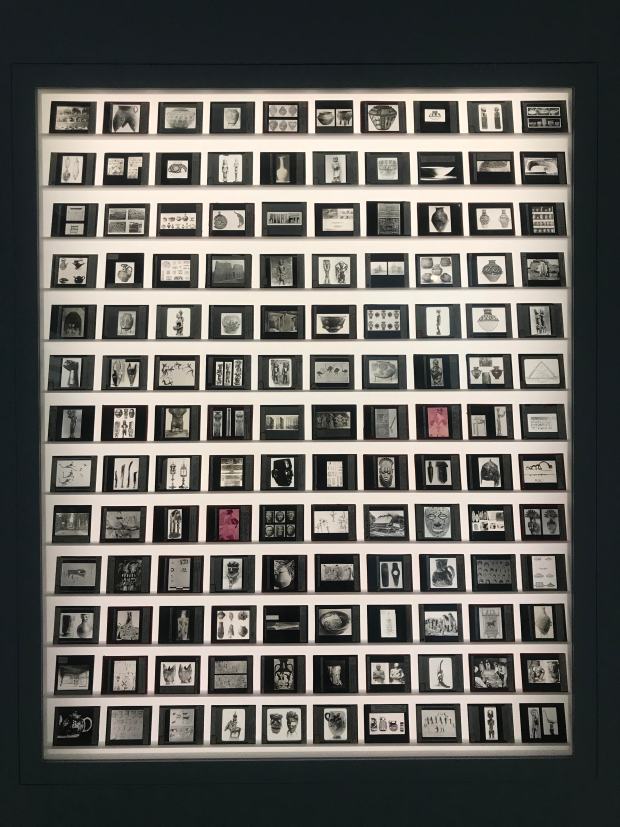

Indeed, if there’s a theme in Gates’ work, it’s the stories and echoes heard from objects and materials those objects are made from. The exhibition will feature, for instance, glass slides Gates recovered from the art history department. Of 60,000 slides, only 50 were of African art; those were also marked “primitive.” For the lobby of the Smart, Gates is creating a new installation using more than 350 African masks he recently acquired. Some are masterful works, but others are tourist trinkets, and when he bought the collection, both disposable and important were mixed together.

“I grew up in a situation where my mom and dad pointed towards happiness whenever they were broke,” he said. “We would go to Mississippi in the summer and it wasn’t a question of do we repair our old barn or get a new one. A new one wasn’t an option. See, when obsolescence is not an option, you look more closely at what you have. My parents were hoarders, they just understood there is more life in a thing than most of us attribute. My practice is partly the demonstration of appreciating the things you have.”

The retrospective, co-curated by Malloy and curator Galina Mardilovich, is the first exhibition that Malloy, a rising star in the museum scene, developed for the Smart after becoming director in 2022. Next year, she’s leading the first Midwest exhibition of the Japanese collective teamLab, known for its immersive, science-based installations. Malloy, whose doctorate in art history considered the ways modern science influenced modern art, imagines “the next chapter for the Smart going beyond Humanities. How do we partner with physics? Computer science? Chemistry?” She also anticipates a renewed commitment from the Smart, now in its 50th year, to local artists.

“I got to know Theaster when I was approached for this job,” she said. “Until then I hadn’t really appreciated the depth to which Chicago influenced his work or how he influenced the city. I asked him if he ever had a big solo museum show. When he said no, that sounded like a lost opportunity. I’m saying this as an outsider who only moved to the city two and half years ago, but perhaps Chicago didn’t appreciate what it had?”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com