Anyone who has recently waited for a Red Line train can tell you about discontent with the CTA. Safety and consistency are so bad that the situation has led people to swap their CTA cards for car keys.

The CTA’s woes have political rivals Ald. Andre Vasquez, 40th, and Ald. Brendan Reilly, 42nd, agreeing on removing Dorval Carter Jr. as leader of the CTA.

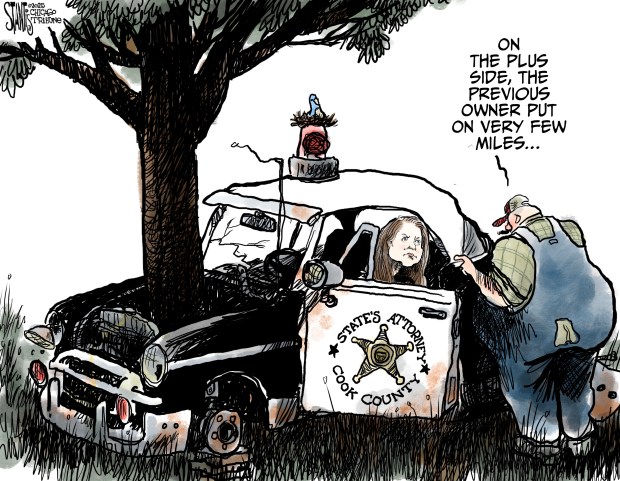

Mayor Brandon Johnson’s response? Appoint another political insider to the CTA board with no transit expertise. But problems facing the CTA are bigger than one person or agency. Filling Chicago’s business vacancies and recovering ridership are the best steps forward.

Chicago lags other major cities in trying to recover its pre-pandemic ridership. The CTA’s new dynamic scheduling lacks meaningful, consistent trains. Under Carter, the CTA saw a decade-high crime wave, numerous operator vacancies and a rise in “ghost trains” that suddenly disappear from the CTA’s online tracker. Worse, it faces a $577 million budget shortfall by 2026.

Illinois lawmakers are seemingly taking the problem into their own hands by introducing legislation to consolidate Chicago’s transit agencies, including the CTA, Metra and Pace, based on a recommendation from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

Combined, the Chicago transit agencies face a $730 million deficit. If consolidation moves forward, the city could save $200 million to $250 million a year, after upfront costs.

But CMAP’s proposal includes a $1.5 billion funding request for transit and at least $400 million annually in complementary capital investments — recommending new fees on drivers and expanding the sales tax to pay for it.

New fees might include a “congestion” or transit tax in Chicago — a fee on drivers passing through high-congestion areas of the city. Vasquez has previously supported this type of tax, and the Chicago City Council Office of Financial Analysis has already recommended it.

Consolidation is flashy, but this proposal may cost the city more than it saves. Ultimately, transit funding isn’t the problem; it’s spending.

The 2024 CTA budget is already the largest ever, as was Metra’s. Instead of finding ways to make the city more affordable and attractive to new residents and businesses, the city wants to continue spending as if nothing has changed. At the rate the city is spending, even after consolidation, Chicago’s public transportation will likely have to raise rates, cut services or get new tax revenue from the city to offset the growing deficit.

All of these “solutions” ultimately punish Chicagoans, especially low-income residents, and existing riders. Everyday Chicagoans feel the pinch from higher transportation fares, fines and fees far more than a guy making more than $375,000 to lead the CTA into a hole.

Consolidation could help cut administrative fat such as Carter’s — who has one of the highest salaries among public leaders in the city — but the state needs to think about its transit problem as an extension of Chicago’s record-high office vacancies. Chicago’s high taxes are driving out residents and businesses, derailing hopes of recovery. If the city doesn’t lower the cost of doing business in the Loop, public transit may never get back on track.

The city can start by exploring ways to ease Chicago’s high commercial property tax. Effective property tax rates need to come down to put us in line with even the most heavily taxed large cities.

Lowering property taxes will encourage businesses to do their part too. With soaring rent costs, businesses can’t afford to bring employees into the office. When remote and hybrid jobs exist, no one wants to pay to commute. Businesses need to stay competitive. Offering transit stipends is becoming increasingly popular as a low-cost benefit that incentivizes workers. Because it’s often minimum-wage earners and shift workers who don’t have the means to work remotely, transit stipends would alleviate a financial burden.

An analysis by the Illinois Policy Institute shows that if the CTA recovers pre-pandemic ridership by 2026, that would bring farebox revenue to $544 million and eliminate $163.6 million worth of its projected deficit. However, based on current recovery rates, the agency won’t meet the ridership goal until 2030. Slashing the commercial property tax rate to fill office vacancies would cut this recovery time — the longer it takes to recover riders, the more the deficit will grow.

The city doesn’t need to tax its residents and workers to fix Chicago’s public transit problems. Instead, cutting city taxes to attract businesses offers a path to safer, more reliable and affordable public transit.

Micky Horstman is the communications associate for the Illinois Policy Institute and a contributor to Young Voices.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.