Brian K. Mitchell is an educator. As the director of research and interpretation at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, he is knowledgable about the gravitas of history and the responsibility carried by recorders of history.

So it’s not unusual to see him on the road borrowing and returning artifacts from places like Geneva and St. Charles, or at gatherings like one in Jacksonville, Illinois, in February that brought together stakeholders to talk about the creation of a Freedom Corridor — an initiative that aims to connect the history of freedom seekers in Illinois with the sites that hold their history.

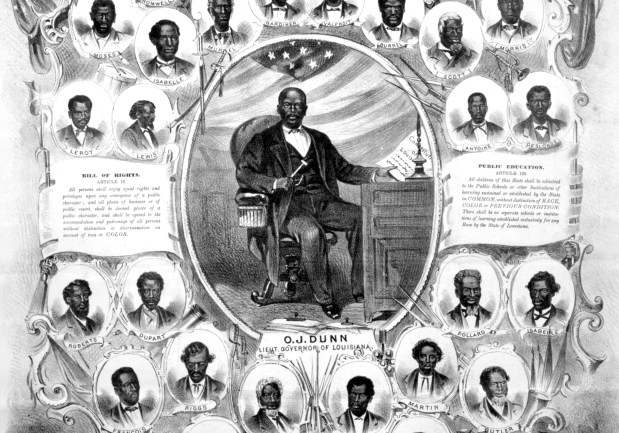

Mitchell is a font of information on Black history, so it’s not surprising that he himself is connected to history. Mitchell is a descendant of Oscar James Dunn, the first elected Black lieutenant governor in Louisiana and the United States. Dunn was elected in 1868 and eventually served as acting governor for 39 days during his tenure, which lasted until 1871.

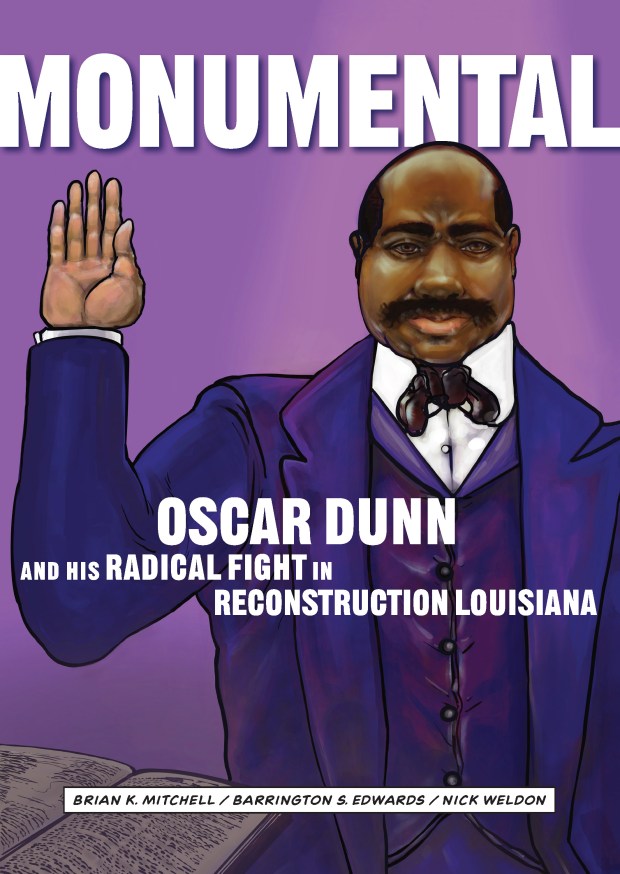

Dunn’s life is the focus of Mitchell’s book, “Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana,” a graphic novel. Mitchell learned of Dunn’s story when he was 8 years old from the oral history that his great-grandmother passed down to him while he was living with relatives in New Orleans, after leaving Chicago.

Mitchell said his curiosity led him to write his doctoral dissertation on Dunn. Years of research culminated in the book, which was published in 2021.

“I read newspapers from all over the country,” Mitchell said. “I followed what was going on in New Orleans in regard to race, day by day. I read (Freemason) records that connected him to the Masonic Lodge and talked about his participation as being the leader of Prince Hall Masons for the state of Louisiana. I looked at records of the legislature. I looked at city council records. I looked at church records that connected him to the AME Church that was in the city. It was an exhaustive amount of primary source work, looking at these firsthand documents that were created during the period, and things that were done immediately following his death by people who had known him.

“I found far more than I imagined would be out there, because the breadth of what we knew about him before the dissertation was 24 pages on his life. So, this idea that you could publish something 300 to 350 pages to cover this life of his, who at that point people thought of as sort of an obscure individual, was seen as unlikely even by Black scholars at the time.”

Brian K. Mitchell is the director of research and interpretation at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield. He is the lead author of the book, “Monumental: Oscar Dunn and His Radical Fight in Reconstruction Louisiana.” Mitchell is a descendant of Dunn. (Camille Guess-Mitchell)

Dunn was enslaved with his mother and sister until his stepfather bought their freedom; he was a guitar player, a plasterer and an advocate for civil rights, fair pay, integrated public schools and universal male suffrage. Dunn started a co-op bakery where freed men would pool their resources for bread, with plans to reinvest bakery profits to use in other trades for the Black community, like construction and blacksmithing.

Dunn was the running mate of Henry Warmoth, an attorney from Illinois who was known for his corrupt ways. Mitchell’s book said Warmoth profited from his position, making $1 million during his term as governor, on an $8,000 annual salary. Warmoth was quoted in a Chicago Tribune article saying, “I don’t pretend to be honest. I only pretend to be as honest as anybody in politics. Why, damn it, everybody is demoralized down here. Corruption is the fashion.”

Dunn died in 1871 under mysterious circumstances before reaching age 50. Rumors circulated of his assassination by rivals. After his death, the Louisiana legislature elected state Sen. Pickney Benton Stewart Pinchback, another Black Republican, to replace Dunn as lieutenant governor. Pinchback was the second African American acting governor of Louisiana. Prior to Dunn’s death, Pinchback allegedly threatened Dunn about revealing scandalous information, which led to rumors about Pinchback being involved in Dunn’s demise.

“In his early political career, there’s a lot of wanting to be at the top of the heap, figuring out ways you can make money and move ahead,” Mitchell said about Pinchback. “The thing that is very different than Dunn, is Dunn seems to have been the reluctant politician. He didn’t want the position. He had just gotten married. He wanted to be at home with his family and run his business.”

Mitchell said it was Dunn’s wife, Ellen, who motivated him to become lieutenant governor. “His wife is urging him to do it. So in many ways, her commitment is as strong as his, if not stronger than his — this idea that we have to do what’s right,” he said.

Dunn eventually met with President Ulysses S. Grant at the White House during his tenure. Grant disliked Warmoth and favored Dunn so much that it was reported Dunn was being considered as a possible running mate for Grant in the 1872 election, according to “Monumental.”

“There’s a larger importance to these graphic histories,” Mitchell said. “Even though histories are coming out and … are well documented, well researched, a lot of adults have put their fingers in their ears and just ignored it. But if there’s going to be change, I believe very much in what Dunn did. The reason he wanted to integrate schools is he believed that it’s hard to change adults’ minds, but if we have children growing up experiencing each other, we can erode racism in this country. There’s difficult stories that need to be told.”

The Tribune talked with Mitchell about Dunn’s life during Reconstruction and the importance of graphic histories. The following conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: In doing this graphic history, were your thoughts that the information shouldn’t just be for academia, it should be for young folks too?

A: I had considered doing a graphic history, but I didn’t think this was going to be the one that I did. The thing that changed my mind was a phone call I received when I was teaching. … It was a young man and his father and the young man had read the Dunn text, and I was like, “Why would you be reading a dissertation?” He was in a gifted program at his school and the dissertation was assigned to him as reading. I was like, “Nah, he didn’t really read this.”

So you begin to ask questions: What part of the dissertation did you like? What didn’t you like? Who were your favorite characters? And he went on to sit down for about an hour and just talk to me about what he liked and what he didn’t like and the questions he walked away from the book with. At the end of the call, I asked him, “How can I get other people your age interested?” And he asked, did I like comics growing up? I said, yeah, I loved comics growing up. And he said, “Wouldn’t it be awesome if you could do this as a comic?” I walked away from that conversation with that idea.

Q: Was the book title a result of Dunn’s monumental feat as being the first Black person in that environment or was it more coinciding with the Confederate monuments movement in America, in taking those down?

A: Initially I was going to call it “Giving Roots to the Rootless.” This idea of having a past grounds people, and they can aspire by looking at these heroes in the past. If you have no past, you’re like a plant with no roots. But there was so much going on around monuments at the time that we thought it important that we make this connection between the past and present and then as things began to escalate, we saw that the country became more polarized. We can point to instances during Reconstruction history where similar things had happened. This was one way for us to tell people, “This has happened in our nation before.”

Q: How do you talk about the book to audiences?

A: If a class is reading the book, I’ll Zoom into the class, and talk about the book. … I’ll Zoom into libraries if libraries are doing programming about the book. I’ve done probably a couple hundred of them. The (publication) press was also awesome. They were able to set aside a lot of time to promote the book and establish a foundation to support getting the book for communities or classrooms that really traditionally couldn’t afford the book.

Q: Have you gotten pushback from the book-banning masses?

A: This was a hard one for them. He was a Republican, so it’s the Republican Party, and they for years have touted him as being in their party. So what are they going to do now? Are they going to turn around now and say, “No, we only liked some Republicans in the past.” No, it hasn’t gotten the kind of pushback that other books have. In fact, it was widely embraced in academia.

Q: How do you get people to take their fingers out of their ears to accept and retain this history?

A: I taught a class on urban history. And we talked about race in the cities. And after the class, a lot of the kids who were suburban and had grown up in these white flight suburbs said we had no idea any of this stuff happened. This is the first time we heard about any of this stuff from this context. …

These things aren’t being readily taught, particularly in schools in the South. So what replaces that is whatever their parents tell them. Why do all the Black people live in the city? They all wanted to live together. And that’s not the reality of what happened. It doesn’t take into account postwar GI bills and the way the realty industry had manipulated it such that Blacks couldn’t go to suburbs. It doesn’t talk about the moving of Black communities, the removal of Black communities through some clearance and sanitation laws.

Q: Where are we with the production of a monument for Dunn? Does he at least have a street named after him?

A: When I was growing up, the only way you saw something of Dunn was if you went to St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, and you knew where his tomb was. In the ’90s, they put a plaque on his tomb and they repaired it and did whitewashing; it was beautiful. I went to that ceremony; it was attended heavily by the Masons. I was able to engage the Masonic lodges again and several of the state senators are members of the Masonic Lodge and put forward a measure to create a bust for Dunn so that money’s already been allocated. There will be a bust of Dunn that will be in the state’s capitol. Overlooking Jackson Square in the French Quarter, there is Washington Artillery Park, renamed in honor of Oscar Dunn. I’m waiting for that park’s dedication ceremony and for them to put a plaque there in honor of Dunn.

Q: Are you going to dive into the life of Dunn’s wife, Ellen Dunn-Burch, who worked for the U.S. Mint?

A: The head countress. I did a short article for “64 Parishes” that covers the positions she had, her rise to power. Such little is known. I’ve been finding little letters that she wrote to President (Rutherford B.) Hayes after the election of 1876, saying, “Look, they’re destroying the Black community in the South right now and you have to step in and do something.” You don’t really think of the first women or these African American women as writing a president. She becomes an early female advocate for the African American community.