More than 112,000 Illinois residents have been deemed too dangerous to own guns, but the state doesn’t know if 84,000 of those people still have them, according to a new analysis by the Cook County sheriff’s department.

The number lays bare a public safety risk that authorities have warned about for years, as the state remains unable to ensure that people surrender their weapons after their firearm owner’s identification cards have been suspended.

And despite several deaths at the hands of gunmen with revoked FOID cards, the number of unchecked revokees continues to grow. Between October 2023 and March 2024, the state’s total number of noncompliant revoked gun licenses grew by more than 1,000, according to the study.

Felony indictments are the most common reason for a resident’s card to be revoked, followed by mental health concerns and domestic violence-related infractions.

“At the rate we’re going statewide, we’re never going to catch up,” Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart told the Tribune. “You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure that out. What we’re seeing is beyond frightening.”

Dart released his analysis to call attention to the revocation issue, which he says is severely underfunded and growing increasingly dire.

As of December 2023, for example, nearly 12,000 Illinois residents had lost their FOID cards after being declared “clear and present” dangers to themselves or others. More than half of those people have not accounted for their guns, according to the analysis.

“There are a lot of different views on gun ownership. I get that,” Dart said. “But I’ve never met anyone who said, ‘no, no, no. Let someone who is deemed a clear and present danger keep their guns.’”

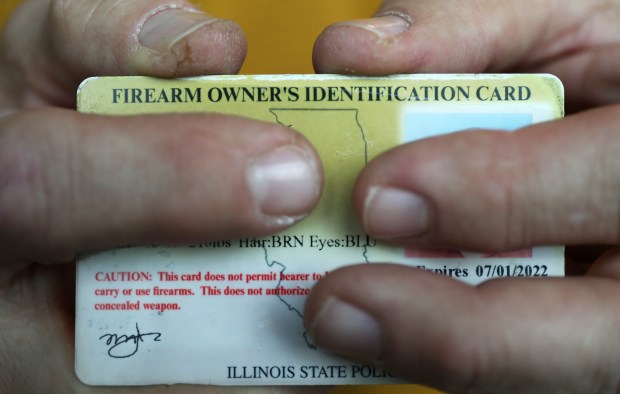

Illinois is one of 11 states that require gun owners to get a license before purchasing a firearm. The application includes a criminal background check, though the federal databases used for the standard inquiry have significant gaps in information.

The cards cost $10 and expire in 10 years, but they can be revoked for several reasons, including felony convictions or indictments, convictions involving domestic violence, becoming the subject of an order of protection or being deemed a mental health risk. People who are dishonorably discharged from the military or determined to be in the country illegally also can have their licenses rescinded.

Those who receive revocation notices must surrender their FOID cards to their local police department within 48 hours and fill out a form stating their guns have been transferred either to police or to a legal gun owner.

Most police agencies fail to act on the letters, largely because they don’t have the money to prioritize revocations and they don’t want to risk officer safety.

The broken system was exposed in 2019, when a disgruntled employee opened fire at the Henry Pratt Co. warehouse in Aurora, killing five co-workers and wounding five officers before dying in a shootout with police. The gunman, a convicted felon, had his FOID card revoked in 2014 but was never forced to relinquish the Smith & Wesson handgun he used in the shooting.

Seven months later, a Joliet man fatally shot his 18-month-old son with a .22-caliber Ruger — one of at least three handguns in his possession despite having his FOID card rescinded more than a year earlier because he had been charged with aggravated battery for brutally beating a man in a parking lot.

In the wake of the Pratt shooting, Illinois State Police made major changes to how FOID card revocation details are shared among law enforcement, taking the unprecedented step of creating a portal listing every revoked cardholder statewide.

The database, which is accessible to most police departments, includes crucial details about firearms purchasing history for each revoked cardholder and the reason for the revocation. It also states whether revoked FOID holders have turned in their cards and legally transferred their guns to someone else’s possession.

Amid public outcry, state lawmakers also allocated $2 million for revocation enforcement efforts statewide. This fiscal year, Illinois State Police awarded $1 million in grants to 16 police departments — most of them in Chicago and the surrounding suburbs — to perform compliance checks on owners of suspended FOID cards.

An Illinois State Police spokesperson told the Tribune that Dart’s office also received a grant for $703,805 in 2023, but it failed to spend the whole award. About $325,000 went unclaimed, the state agency said.

It received a smaller amount this year because the Chicago Police Department received revocation enforcement money for the first time, thereby reducing the amount given to Cook County. Still, Dart’s office received award $333,293, but nearly $80,000 of it remains unclaimed.

In 2019, a Tribune analysis found that about 7 of every 10 revoked FOID cardholders failed to account for their firearms. The statistic has remained unchanged in the past five years, despite the additional funding and renewed commitment.

Dart — who has had a revocation enforcement team in place since 2013 — argues $2 million is not nearly enough, as evidenced by the growing backlog. He is asking lawmakers to earmark between $10 million to $20 million to address the problem.

“The $2 million allocated after the (Pratt) shooting doesn’t go very far,” Dart said. “I don’t think people understand the issue. I don’t think they understand the magnitude of it.”

The Illinois State Police, however, questions why Dart would ask for more money when he has not fully used the grants awarded to him.

“We would be happy to work together to identify additional funding if the county was able to demonstrate that they needed additional funding,” spokeswoman Melaney Arnold said.

The Illinois State Rifle Association also did not return calls seeking comment. The organization has supported revocation enforcement in the past, but has staunchly opposed raising FOID fees to pay for it.

Dart said his revocation team has cleared its backlog in the communities under its jurisdiction, which includes unincorporated areas and Ford Heights. However, the overall number of revoked FOID holders who have not complied with orders to relinquish their permits and transfer any weapons in their possession continues to grow in Cook County, according to the sheriff’s analysis.

Between April 1, 2022, and December 30, 2023, the list of noncompliant revocations in Cook grew by an average of 147 every month, the report found.

As of December 2023, more than 1,300 Cook County residents lost their FOID cards after being declared “clear and present” dangers to themselves or others. Nearly 45% of those people have not accounted for their guns, according to the sheriff’s analysis.

“It is absolutely depressing,” Dart said. “Because, once again, we have identified the issue, have unanimous agreement that guns in the wrong people’s hands are a bad thing and we’re not taking them away. And you know, five years after those horrible incidents we’re worse off than we were before.”