A ceremony honoring steel workers who were killed while trying to organize a union sparked an idea in Terry Steagall’s mind.

The ceremony, an annual event, was at a sculpture on Chicago’s southeast side that honors the 10 workers — including five from Northwest Indiana — who were killed by Chicago police while they were marching toward the nearby Republic Steel plant on Memorial Day in 1937.

A former steelworker himself, retired now after 41 years at Inland Steel (now Cleveland-Cliffs) in East Chicago, Steagall began thinking of other workers who had been killed but didn’t have a place to honor their memory.

“I think part of my inspiration was going over to the Memorial Day ceremony for the guys who got shot at Republic Steel,” he said.

Since then, Steagall has devoted himself to memorials to workers who were killed on their jobs or while trying to form a union.

“We tend to forget the workers who died,” he said.

In recent years, he has prodded public and union officials to get a memorial for workers who died in the Cline Avenue bridge construction in East Chicago in 1982, and he has raised money for a memorial in Hammond for workers who were killed trying to organize a union in 1919.

Steagall was working in Inland Steel’s machine shop on April 15, 1982, when Indiana’s worst construction accident happened not far away.

He heard the wailing sirens as ambulances and fire trucks raced to the scene. But, in the days before cell phones, he didn’t find out until later what had happened.

Collapsing sections of the Cline Avenue bridge, under construction then, had killed 12 construction workers instantly; two more died later from injuries.

Some years later, Steagall began thinking of memorials for workers.

“Thirty-one people died in the 41 years I was there (at Inland Steel),” he said. “At safety meetings, we’d have to review those accidents.”

At one point, he thought of organizing a memorial to all the workers, including police and firefighters, who had been killed in East Chicago over the years, but now he has focused on the Cline Avenue bridge workers.

“I thought these guys were kind of forgotten about,” he said.

Earlier this month, he spoke to the East Chicago City Council about the Cline Avenue tragedy and asked for a resolution or proclamation in memory of the 14 workers who died. His request was referred to a committee.

The Lake County Board of Commissioners gave a fuller response the next week, passing a resolution by Commissioner Michael Repay honoring the memory of the Cline Avenue bridge workers who died, extending sympathies to their families and loved ones, and recognizing “the ongoing efforts to establish a permanent memorial in remembrance of this tragic event.”

Steagall said he has gotten little response so far from the construction union representatives he has approached about the proposed memorial.

But that’s not the only workers’ memorial he has worked on.

On Sept. 9, 1919, four men were killed and 62 people injured when gunfire erupted as a crowd of striking workers at Standard Steel Car Company, in Hammond, approached the company’s main gate.

The Standard Steel Car factory later became a Pullman-Standard factory, which made rail cars there until 1980. Industries still occupy much of the area where the plant stood.

The Hammond Historical Society, which printed a booklet about the strike and the workers’ deaths in 1974 and reprinted it in 2019, had been looking for a way to honor the workers. First, they thought of putting markers on the four men’s graves at a Chicago cemetery, but the cemetery had lost track of where the men had been buried.

Now, the plan is to install a memorial where the men were killed.

Steagall became interested in the project after attending a memorial event at the Ophelia Steen Center, which stands near the shooting site, on the 100th anniversary of the shooting.

Later, he raised about $5,000 from the Steelworkers Union and individuals.

“Terry has stuck with us through this whole thing,” said Ruth Mores, a former Hammond Historical Society vice president. “He stays involved until he gets the answers.”

She said the historical society plans to have a memorial, about the size of a large cemetery stone, engraved with the four workers’ names.

They plan to install it on land at Columbia Avenue and Highland Street, near the site of the shooting, on the anniversary of the 1919 shooting.

Plans for a memorial to the Cline Avenue Bridge workers also may be coming together.

Steagall has thought of a site at Block and Michigan Avenues in East Chicago, near the Cleveland-Cliffs plant and a Cline Avenue exit.

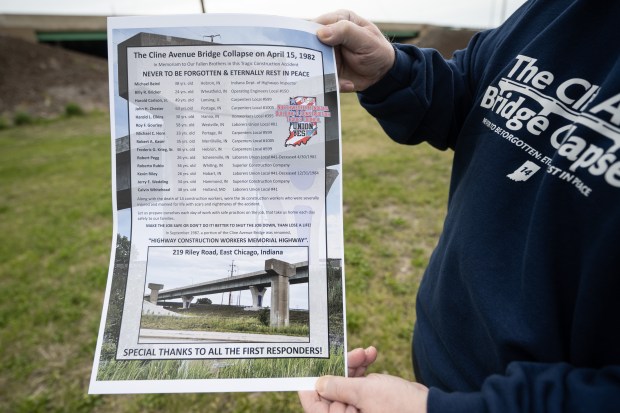

He recently placed an 11-by-17-inch poster there, bearing the names of the 14 men killed in the bridge collapse.

But another site could have a more direct connection to the tragedy.

The state’s highway department built a new Cline Avenue bridge after the 1982 disaster, but that bridge had to be closed in 2009 when deterioration set in and made it unsafe.

Most of that bridge was demolished, but a few of its piers, built to support the highway, still stand near the site of the 1982 collapse.

The state declined to build a new Cline Avenue bridge, so a private company built the current two-lane bridge, and United Bridge Partners operates it as a toll bridge.

Terry Velligan, general manager of United Bridge Partners, said he believes one of the old bridge’s piers would be a good site for the workers’ memorial.

“It’s right off Riley Road, and we own the property,” he said. “It’s accessible to traffic.

“And you’d be standing on the ground where it happened.”

Velligan, who grew up in East Chicago, said he has talked to representatives of several skilled building trades who would be interested in working on a memorial there.

“People could sit down there, and they could have remembrances every year,” he said.

Tim Zorn is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.