Pregnancy loss can be difficult enough, but women who have been through it say society often doesn’t want to hear about it.

It wasn’t always like that, said Rebecca Little, who co-wrote “I’m Sorry for your Loss,” with Colleen Long during a recent talk sponsored by the Palos-Orland League of Women Voters.

Long, who covers the White House, law enforcement and legal affairs for the Associated Press, was in town on assignment. Little is a freelance writer who has written for the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Parent, and was a contributing editor for Chicago Magazine.

The two women were childhood friends in Flossmoor and attended Infant Jesus of Prague School and then Homewood-Flossmoor High School.

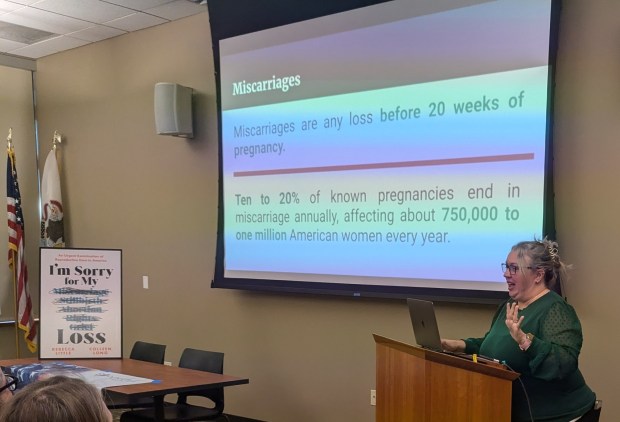

Their book is about reproductive care through the ages, though a focus is pregnancy loss, specifically losing a fetus before 20 weeks, and abortion, and how politics have affected both.

They both lost a pregnancy late term, giving them a first-hand look at what women experience. The authors say more than a million people lose a pregnancy each year.

“Society really fixates on abortion and the perfect pregnancy and ignores everything in the middle,” said Little, saying that attitude “laid the groundwork to overturn Roe v. Wade.”

She said the statistics on miscarriage, chemical pregnancy loss and still birth are probably higher, but said there is a lack of data

“You must grieve, but privately. ….You can be sad but wrap it up,” she explained. “Why are we like this?

In Colonial times, miscarriage was looked at differently, she said.

“Miscarriages were often welcomed as a reprieve (between having babies),” Little said. “Abortion was commonly attempted before 20 weeks.”

In 1748, Benjamin Franklin even added a recipe for at-home abortion in a British math book, she said.

Up until the mid-19th century, healing was mainly a female thing and childbirth was done at home, she said. Then in 1857, Dr. Horatio Storer “led a crusade against abortion and contraception.”

“A lot of these doctors were religious … anti-feminist,” said Little.

Black women were also used in gynecological research/surgery without anesthesia, she said.

“The entire field of gynecology is based on cruel and racist experimentation on enslaved women,” Little said. “The notion that Black women didn’t feel pain is still a problem today.”

Women had an average of seven children in 1800, which dropped to an average of 3.56 in 1900 as society changed from farming to working outside the home, Little said. After World War II, she said maternal mortality plummeted with the onset of antibiotics and blood transfusions.

Then in 1960 with the onset of the pill, Little said women could control their pregnancies.

“For the first time, she can have sex and doesn’t have to get pregnant,” Little said.

With the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, abortion was “free from government intrusion, Little said. But attitudes changed after Ronald Reagan’s presidency to become more anti-abortion.

“Since then politics has increasingly focused on the fetus, which led to where we are today,” Little said.

Ilene Yohay, an endocrinologist in the audience, said she was struck by the changes in medical care.

“Midwives knew to wash their hands,” said Yohay, who lives in Flossmoor. “Before, doctors … would go from the autopsy room to the delivery room.”

She said a British surgeon, Dr. Joseph Lister, realized doctors needed to wash their hands and made the connection between dirty hands and disease. Lister also started the use of antiseptics in surgery, Yohay said.

Jim Deiters, a former biology teacher and one of the few men in the audience, said he was glad he came, calling the talk “a true understanding of what happened.” He said he was struck by the risks of abortion that wasn’t done by a professional.

“It’s kind of scary,” he said.

Victoria Cerenich, director of the league, said she was impressed by the book’s writing style and how the authors directly addressed the readers.

“I think we’ve got a crisis approaching us on women’s health care,” Cerenich said. “It’s always been difficult for women to get the attention to their specific needs.”

Little said she and Long could have used a book like theirs when they lost their pregnancies.

“We figured if we had these questions, other people probably did, too,” Little said. “So we set out to answer them ourselves.”

Janice Neumann is a freelance reporter for the Daily Southtown.