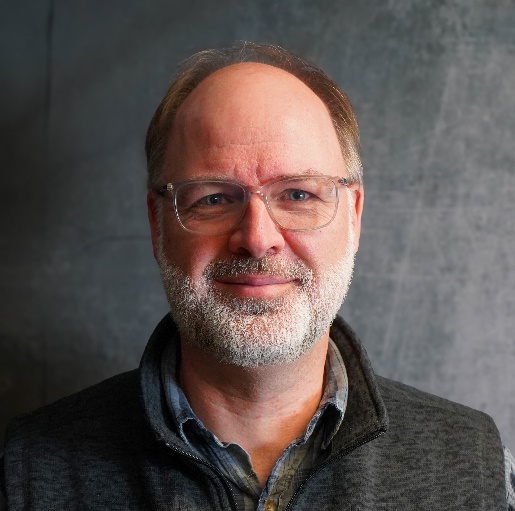

When Jason Taylor steps into his role as superintendent of Indiana Dunes National Park this spring, he will bring with him wide experience working in natural areas and with diverse people.

It also will be his introduction to the Indiana dunes region.

“I’m looking forward to getting on the ground there – hearing, sensing, and all the things you can’t do when you drive through,” he said in a phone interview.

His appointment as the park’s superintendent was announced by the National Park Service’s regional office on Friday. The previous superintendent, Paul Labovitz, retired last summer after a nine-year tenure.

Taylor, who just turned 50, plans to begin working remotely as superintendent in April and to move to the region in May with his wife and two children.

His professional work experience — with the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and an international organization — has been in Montana, Alaska, the Arctic and Massachusetts.

But his roots are in Michigan.

He was born in Flint, grew up in a town near there, and earned his college degrees in the state – his bachelor’s in biology at the University of Michigan-Flint, and his graduate degrees, including a doctorate, at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Taylor’s only contact with Northwest Indiana so far has been in driving through on his way between Michigan and Chicago.

His graduate work in Michigan focused on interactions between humans and the environment, particularly in land-use policies.

That’s a subject he sees as particularly relevant to the Indiana dunes and Northwest Indiana, where unique natural areas sit near heavy industrial sites as well as homes.

Indiana Dunes National Park, he said, is one of the most biologically diverse national parks, and he was happy to learn that the dunes region played a role in the development of ecological science in the early 20th century.

He was glad to hear, too, about development of the Indigenous Cultural Trail outside the Indiana Dunes Visitor Center, commemorating the original Miami and Potawatomi residents of the region.

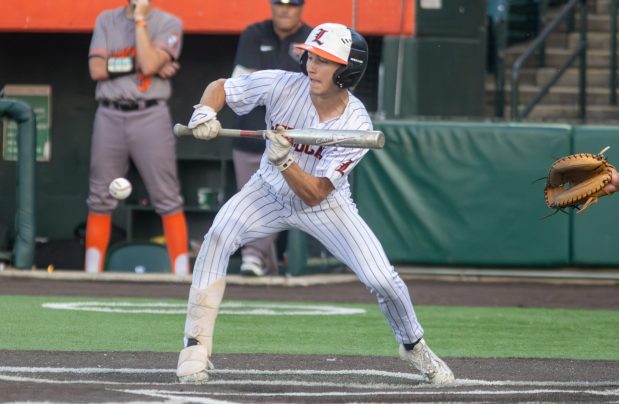

Pokagon Band of Potawatomi citizen Skyler Alsup performs a Great Lakes-style dance during a celebration of the completion of the first portion of the Indigenous Cultural Trail at the Indiana Dunes Visitor Center on Wednesday, Sept. 27, 2023.

The day before his appointment as Indiana Dunes National Park superintendent was announced to the public, he met remotely with representatives of local organizations that work with the park.

“That shows me that the partners care a lot,” he said. “I’m really excited to be part of the community, and to see how we can work together.”

A landscape ecologist, Taylor has worked for nearly four years at the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute, on the University of Montana campus in Missoula, Montana.

Previously, he worked for the National Park Service from 2016 to 2020 in Alaska, first as the regional chief for natural resources at the Alaska Regional Office in Anchorage, and then for about a year as superintendent of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park in Skagway.

His other National Park Service experience was from 2013 to 2015 as chief of natural resource management and science at Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts.

Between those two National Park Service stints, he spent six years with Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, coordinating biodiversity monitoring programs with the eight nations and the indigenous peoples of the Arctic region.

He visited every country in that group except Russia, and valued his experience “working with people who think differently than I do.”

The work there, Taylor said, was “kind of like a mini-United Nations.”

He sees that experience as valuable in working with the diversity of groups in Northwest Indiana.

Tim Zorn is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.