Since her high school biology class when she had to trace a drop of blood through the body, Ida Urbano has been “fascinated by the heart.” So she’s spent the last four decades helping people stay healthy by scanning theirs.

“After I graduated, I became an EKG tech,” she said. “I just fell in love with the heart and knew that was where God wanted me, so I (eventually) went to school for ultrasound.”

As part of a work program in high school, Urbano, 62, attended classes in the morning and went to a hospital nearby to learn clinical tasks. When she transitioned to ultrasound, she attended Medical Careers Institute in Chicago. “They didn’t have it at the colleges – that’s how long ago it was,” she said, adding that she was certified in about six months because she was already in the field.

The Crestwood resident worked at St. Francis/MetroSouth Medical Center in Blue Island for years until it closed in 2019, and she went to work for a cardiologist with Duly. Her hours got cut, so she came to Palos Community Hospital during the pandemic about five years ago, before its sale to Northwestern Medicine.

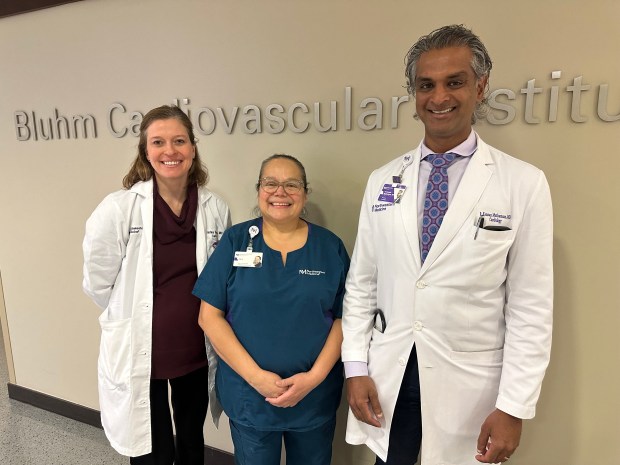

Urbano, one of about 15 sonographers at the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Northwestern Medicine Palos Hospital in Palos Heights, typically performs six or seven echocardiograms, or echos, each day depending on the patients. “The more abnormalities you find, the more pictures you have to take and the longer it takes,” she said, adding that an average scan lasts about 45 minutes to an hour, which includes her report.

If a sonographer finds something worrisome, the doctor gets a phone call right away. “If it was something serious, we wouldn’t let the patient go anywhere!” she exclaimed.

Urbano said staff have monthly meetings each month with a cardiologist about specific topics and go through what’s expected. “That keeps everyone on the same page. We’re all learning together and have to follow protocol,” she shared. “These doctors are brilliant. We are continuously learning.”

Technology has evolved during her time as a sonographer. “It’s so amazing what we can see now that we couldn’t see back then,” she said, especially the 3D images with transesophageal echoes, done through the esophagus to get close to the heart. “The doctor does it, but the tech is the one who does all the measurements,” Urbano explained. “They use it a lot when they’re doing surgery to put new valves in.”

At a recent meeting, Urbano learned that the hospital is starting to look into artificial intelligence. “I always said AI couldn’t take over my job, but they’re working on it. The tech gets the main picture and the machine has the capability of rotating the image,” she said.

Urbano said she’s getting close to retirement, but she’s not sure that will happen anytime soon, even though it’s a fairly demanding physical job. “We have positions that are called ‘flex,’ where you can come in when they need you. I love it so much I don’t think I could be away from it totally.”

Having someone with Urbano’s experience is invaluable, said Dr. Kristine Quinn Degesys, Echocardiography Lab director for the institute. “Not only does she have this long experience where she knows how to speak with patients to have to get the images, but she’s seen the technology change and adapt, and she’s had to change and adapt with it, which is a skill within itself.”

The scans Urbano does are important. “It’s one of the primary tools we use to take a look at the function of the heart and the structure of the heart,” Degesys explained. “If there’s any concern about someone’s heart-pumping function or structure, this is the best way to take a look.”

The cardiologist enjoys working with Urbano. “She’s upbeat, positive, always has a good demeanor,” she said. “In regard to her professional work, which is very inquisitive, she’s a perfectionist with images. She takes her work very seriously and takes pride in her work.”

In fact, Urbano’s thoroughness was key to helping diagnose a patient last year with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a heart disease with few symptoms, after she had passed out.

“Ida took those pictures and brought it to the physician’s attention, and now the patient is on the right track to be treated for this,” Degesys said. “She’s doing great work every day, very important work.”

Dr. R. Kannan Mutharasan, medical director of the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute at Palos, called sonographers “the eyes of the cardiologist,” a helpful resource for the 15,000 scans done across the hospital’s three sites in the south region.

“They are the ones who take pictures of the heart and in so doing help show where disease might be or what’s healthy. Beyond that, I think it’s that personal touch. It’s a relatively intimate procedure,” he explained. “A lot of it is making the patient comfortable. Placing the probe right against the rib cage, it can be uncomfortable.”

Mutharasan also pointed to the collaboration between doctors and sonographers. “It’s a true partnership. It’s not ‘I’m the doctor and you’re the tech.’ It’s really a constant back and forth. It’s someone whose insights you truly value. It makes all the difference in how we care for patients,” he said.

“I think someone like Ida has a sixth sense,” he said. “Echos, colonoscopies are things where you really want to take your time and look for disease. … Ida might catch something in the corner of her eye and think ‘I want to take a better look.’ It’s like being a detective. If you think of the echo probe as a flashlight, you’re shining that to see what might be wrong. But it’s not light – it’s sound, which leads to the unbelievable pictures we get.”

Although sonographers don’t divulge to the patient what might be seen in a scan, they can try to ease anxiety or alert the physician more quickly. “When someone like Ida says ‘Doc, take a look at this,’ we really pay attention,” he said.

Urbano believes there’s a greater purpose at work in her life, and in her vocation. “I‘m a woman of faith, and it’s the Holy Spirit in me that makes me love patients and care about them,” she said, adding that she offers to pray for patients.

“What people see is the love of Jesus Christ that lives in me, and I know I belong here because this is a place of sickness, it’s a place of hopelessness. We’re dealing with patients who have cancer who have to come in for a serial echos, to check the effects of chemicals on their heart,” she said. “You should see their faces – they just light up. It’s where God wants me to be and to give them hope. God uses all of us – I am the hands and feet of God.”

Melinda Moore is a freelance writer for the Daily Southtown.