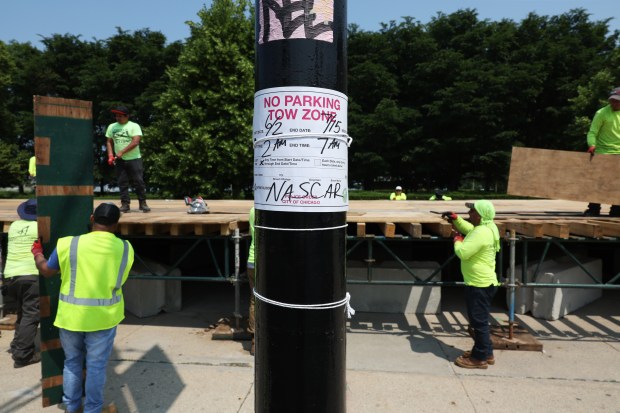

For NASCAR’s Chicago Street Race, closing roads throughout Grant Park so professional drivers can speed past fans has its costs for residents — police overtime, street fixes, lost park access.

Add to that the cost of shutting down on-street parking.

Parking spot closures tied to the race cost Chicago $348,306 in 2023 and another $273,665 in 2024, a Tribune records request revealed.

The over $600,000 in so-called “true up” costs covered by the city and owed to the parking meter system’s private owner further complicates the cost-benefit analysis of the race as the city and racing authority weigh its long-term future.

And it gives Chicagoans yet another tangible reason to detest the city’s lease of its on-street parking to a private entity, a much-loathed 2008 deal that penalizes the city for taking metered spaces out of commission for things like street festivals, construction, or, in this case, a giant downtown race put on by a hugely popular stock car authority.

The cost gives downtown Ald. Brian Hopkins, 2nd, pause even though he thinks the race is gaining support.

“Slowly they are winning hearts and minds,” Hopkins said. “But they have not won mine because of these outstanding questions.”

But despite the parking toll, NASCAR says its Chicago race is still a good deal for the city.

The event has generated $4 million in city and county amusement tax revenue over two years and over $1 million to the Chicago Park District, NASCAR spokesperson Jake DiGregorio said. He said it has also brought in $108.9 million in local economic impact and effectively provided the city with rosy advertising worth $23.6 million through race broadcasts.

Hopkins said he has doubts about the race’s real economic impact and believes it is still not profitable for the city.

NASCAR sweetened the pot this year with a $2 million payment to the city “to ensure that the event continues to be mutually beneficial,” DiGregorio said. At the time, city leaders said the “better deal” would help the city cover the over $3.5 million in police overtime and construction costs it racked up for the first race.

NASCAR and the city have not included the costs to Chicago Parking Meters in their public discussions of those payments. And Chicagoans loathe additional money going toward the parking conglomerate like they loathe May snowstorms and 20-minute Blue Line waits.

The city, not NASCAR, pays the cost, a Department of Finance spokesperson confirmed.

The news about the race parking costs comes just days after the Tribune reported an April arbitrator panel decision determining the city could owe over $100 million to the parking meter company for violating its contract. If it wants to avoid paying in cash, the city might need to turn over even more on-street parking to the company after a final court decision.

Some race costs were sharply cut this year as NASCAR hosted the event for the second time. Shortened set-up and teardown times led to six fewer days of street closures, an improvement reflected in the 2024 race’s nearly $75,000 cheaper cost for closed parking. Certain construction costs, like engineering fees, were exclusive to the first race.

A more thorough accounting of the race’s economic impact for local businesses is expected to come later this fall.

NASCAR and Chicago agreed to a three-year contract to hold the early July street race, again one of the season’s most-watched runs for the racing authority. The contract allows the city or NASCAR to cancel the event six months before the race, though neither has suggested it is considering doing so next year. Signs around the 12-turn, 2.2-mile racetrack in July advertised the 2025 race, though NASCAR has not yet released its schedule for next year.

Pushback against the race toned down this summer as fewer road and park closures affected Loop residents. Several downtown aldermen called last fall for the race to occur on a different date to free up Grant Park over the Independence Day weekend.

The proposal did not lead to change. Moving the race would clash with the contractual obligation for the event to occur in the first weekend of July.

The race agreement includes a two-year option for NASCAR and Chicago to agree to host the race again in 2026 and 2027. But after two race weekends both marked by exciting races ultimately dampened by torrential downpours, its future could be in part shaped by next summer’s third attempt.

Both the city and NASCAR declined to answer questions about possible upcoming races.

Hopkins said Thursday he had previously tried to learn the true-up costs associated with the race, but did not receive answers. He remains undecided on whether the street race should get a Lollapalooza-style, long-term contract, he said.

The $2 million payment added last year is “a step in the right direction,” though any future deal needs to be better for Chicagoans, he said. More and more people seem to be enjoying the race, he added.

“They have earned the opportunity to try to prove themselves,” Hopkins said. “Clearly they are putting their time and effort into making their case that NASCAR should be part of Chicago summer into the future.”

Grant Park’s most famous tenant, the Lollapalooza music festival, provides “substantial funds” to the city, he said.

“I can’t say that with NASCAR. And as long as I can’t say that, I can’t support an agreement with them,” Hopkins said.

jsheridan@chicagotribune.com