Check under the couch cushions and dig through your coat pockets because the era of America’s one-cent coin, colloquially known as the penny, is coming to a close.

The Treasury Department recently confirmed production of the penny will end next year, almost 240 years after the first U.S. pennies were minted. Few are decrying the move, perhaps a sign of its long overdue retirement.

It turns out that pennies are more expensive to mint than they’re actually worth, and there have been calls for their demise going back decades.

The saying “a penny for your thoughts,” which traces its origins to the 16th century — if adjusted for inflation from 1909 when the first modern American penny was minted — would be closer to two quarters, although no one is paying that kind of money for thoughts these days.

The penny is not the first coin to go to the great piggy bank in the sky. Among the discontinued is the half-cent coin, which ended production in 1857, and the two- and three-cent coins were stopped in 1873 and 1889, respectively. There was even a 20-cent coin, although it was only produced from 1875 to 1878.

While there aren’t many penny defenders calling for its continuation, there’s still some nostalgia for the diminutive coin. Dan Smith, president of the Wauconda Township historical society, recalled collecting pennies during the summers of his childhood. They were the easiest, or more accurately cheapest, coins to collect for a young boy, he said.

Smith talked about his summers in the late ’50s and early ’60s, riding his bike to the bank, buying $50 worth of pennies and taking them home in a big bag.

“I could barely steer my bike holding the stupid thing,” he said.

He’d go through the thousands of coins, pulling out the ones he wanted for his collection, replacing them with less-interesting pennies and returning the bag to the bank.

Back then, Smith said, you could still find “Indian head” pennies, which had been produced from 1858 to 1909 and featured Lady Liberty in a Native American headdress. Several of the Depression-era coins were also very rare, as was a variation of the 1960 penny with a small “6” that was later redesigned to avoid confusion with a zero.

“You could buy these little folders, and they would have a little slot for each year,” he said. “The 1960 small-date penny, somewhere in this room, I probably have a roll of those.”

But the rarest of all was the 1909-S VDB Abraham Lincoln penny, the first year the president’s face appeared on the one-cent coin. “S” was for San Francisco, where it was minted, and “VDB” were the initials of the designer, Victor David Brenner. This specific design, with Brenner’s initials on the back, was only produced for a few days, and relatively few of these pennies were minted.

Purchasing power

Carola Frydman, a professor of finance at Northwestern University, said the whole point of money is to more easily facilitate transactions, something the penny has increasingly failed to do.

“Civilizations before that were something close to barter, and that makes transactions really difficult,” Frydman said.

At one point, even salt was used as currency. Gold, silver and other metal coins were used because their material was considered intrinsically valuable. But while metal coins were more convenient than bartering, they were limited by the ability to mine precious metals.

“So, through time, we came to trust our government to issue ‘fiat money,’” Frydman said. “These are pieces of paper that don’t really have any intrinsic value on their own, but we trust the U.S. government in keeping the value of these pieces of paper.”

Coins are a “remnant of that long history,” she said. Today, most people use credit and debit cards or digital wallets, and physical cash in general is experiencing a decline in use. Coins, and pennies especially, are bulky and can be “annoying.” And, as inflation reduces their purchasing power, certain denominations of coins become more and more pointless to carry around.

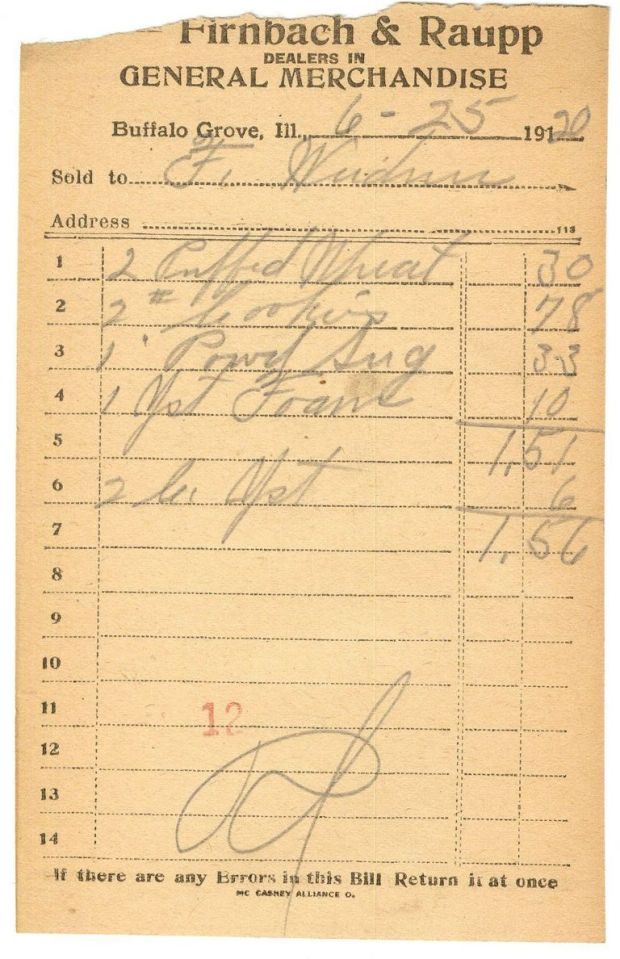

A receipt in the collection of the Raupp Museum in Buffalo Grove shows just how far the penny has fallen. On June 25, 1920, someone bought two packages of yeast from the general store, Firnbach & Raupp, for 6 cents.

Debbie Fandrei, the museum’s curator, said local farmers could even pay with eggs. It was “a reminder that how we pay for things continues to change … even how we value some things continues to change.”

‘A certain nostalgia’

Fandrei, who often works with young children at the museum, noted how even as times change and objects disappear from use, language can remain the same.

“Even the first, second and third graders I work with get what ‘a penny for your thoughts’ means, even if they’ve never had to count out pennies,” she said. “It’s kind of fascinating how something will stay in the language, even after the physical thing itself has left.”

But the penny will likely go the way of other items that were once ubiquitous in American life, as Fandrei has seen in her line of work. She recalled a presentation showing an elementary class an old camera. When the kids asked how it worked, Fandrei explained by putting film into the camera.

“Twenty-six faces turned to me and said, ‘What’s film?’” Fandrei said. “And I thought … ‘Wow I feel old.’”

Another example was bottle caps. Few of the children knew how to use a bottle opener, since they are used to screw-off caps. These were minor instances, she said, but still gave her pause.

“Nothing is the end of the world or anything,” Fandrei said. “But … you stop for a moment when you have to explain something that used to not really be a thing you had to think about.”

Although he still uses coins regularly, Smith wasn’t particularly torn up by the news of the penny’s upcoming demise. Billions have been minted every year, meaning they’ll be around “somewhere” for a long time, from old coin jars to piggy banks, he said.

“I’ve been thinking for years that it should go away,” Smith said. “I probably regret when they stopped making the half-dollar more than I care about the penny.”

It’s a sentiment many today share. The penny can become “just an annoyance” in the modern era, Smith said. But he still picks up every penny he sees on the ground.

“It’s the coin collector in me,” Smit said. “It might be valuable. It never is, but it might be. There’s a certain nostalgia about it.”