Socrates, of all the philosophers in the history of mankind, was probably the biggest pain in the ass. He believed argument itself was the core to understanding anyone, including himself. He didn’t want to convince you. He didn’t want you to agree to disagree with him. He didn’t want you to agree at all — for therein held one’s freedom. On his deathbed, with a solid conviction about what to expect from the afterlife, he urged friends to argue against the existence of an afterlife.

He lived, and died, to argue.

The man had become so annoying that an Athenian court, having decided he was damaging the morality of Grecian youth, sentenced Socrates to death by self-poisoning.

The man was exasperating.

For a brief time, though, Agnes Callard gave him a run for his money.

Somewhat intentionally.

She had spent most of her childhood not being understood and had found Socrates the key to explaining herself and the way she thought about life. So, long before becoming an associate philosophy professor at University of Chicago, before becoming among the most popular teachers on campus, as well as the subject of a 2023 New Yorker profile (partly centered around how she lived in the same home with both her second husband and her first husband), many years ago, fresh out of high school, Callard gently accosted strangers in line outside the Art Institute of Chicago. She asked them the unanswerable.

She sidled up and asked if they were interested in having a philosophical conversation, and when they replied, Uh… yeah, sure, she peppered them with questions, things that no one could reasonably answer, like What is the meaning of life? And What is art?

It didn’t go well.

For one thing, she wasn’t a philosophy major, she just wanted to understand Socrates better. She had studied ancient Greek, she took Greek history classes. “But there was something more I wanted,” she says now, at 49. “And that was to be Socrates. Not to figure him out. To inhabit him, fill his shoes.” To be possessed by the spirit of the Greek philosopher. She was taken by the way Socrates lived “on the edge of himself,” always eager to turn his beliefs and approach to life upside down after a convincing argument.

She went to the stone steps of the Art Institute, the most classically ancient-seeming space she could think of. She felt good about it. When she asked strangers to have a philosophical argument, no one turned her down. The problem was the arguing part:

“I would ask, oh, ‘What is art?’ And they would say you can’t define art. I would say ‘But you defined it well enough to want to see it here today.’ I was trying to challenge them.”

They weren’t ready to be challenged, I said.

“Yes but is anyone ever ready!” Callard said with a fervor that gives you a hint of her younger self. “The people I accosted had at least heard of philosophy and Socrates — more people have heard of Socrates and philosophy now than they did (when he was alive). It should be easy for me to do this! But no, people found me inscrutable. Was I pushing a religion on them? Was I trying to sell them something? I have a very literal-minded personality and I didn’t understand why this wasn’t working, and the more I tried to challenge them, the more they seemed almost uncomfortable and afraid of me.”

If there’s an origin story to Agnes Callard, that’s as good a place as any to start. Her superpowers as a philosopher sprung out of the frustration at getting her thoughts and herself across to people who would care less about philosophy. She began university life as an academic philosopher, writing for academics, but after she was named the philosophy department’s director of undergraduate studies, she became a public philosopher. She began thinking harder about ways that philosophy should be inserted into everyday life. She decided philosophy had to matter to students in Hyde Park who didn’t take philosophy. She started the ongoing “Night Hawks” series of late-night philosophical debates, among the most popular regular activities on campus.

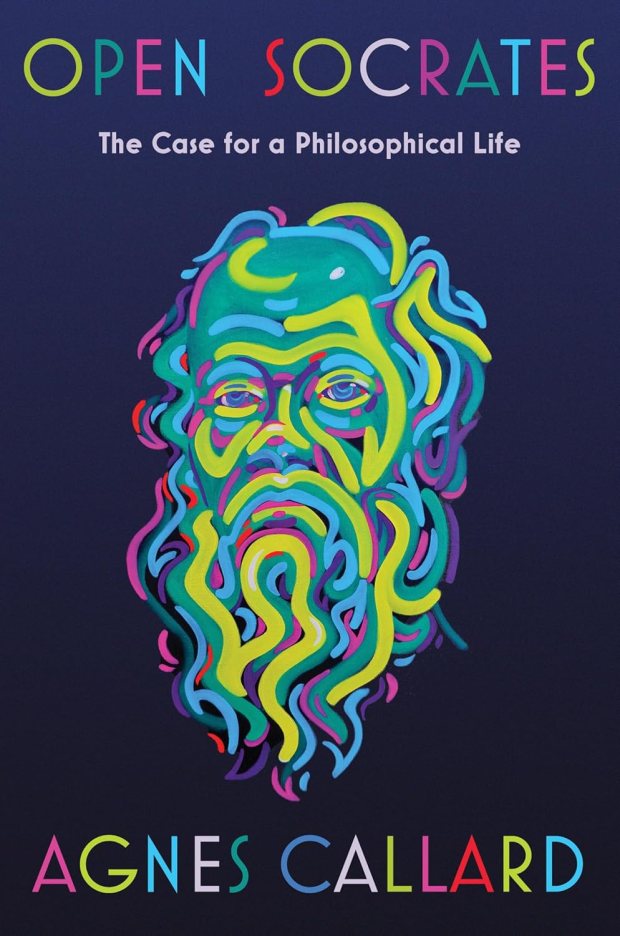

She wrote for publications such as the New Yorker, New York Times and Atlantic about morals and philosophy, as well as anger and ambition and marriage. Her new book, “Open Socrates: The Case for a Philosophical Life,” is her most direct act of public philosophy yet — a self-improvement narrative centered on Socrates’ insistence that we live a more interesting life through the hard work of facing ideas we’re not comfortable with. It presents, in a way, an intellectual roadmap for four more years of a Trump presidency. For most of us, she argues, Socrates is a watered-down “sauce” poured over simplistic affirmations about staying open-minded and fearing the unexamined life (not worth living, Socrates said). His true relevance to 2025 would be that the only thing he knows is the fact of his own ignorance. He was never big into zero-sum arguments.

His famed Socratic Method, Callard writes, only works when you argue with someone “who has taken on a role distinct from yours.” Anything else tends to be performative.

Then, because Callard is nothing if not provocative, she used her employer, University of Chicago, as an example of performative commitment to freedom. She brings up the school’s much-discussed statement that free speech extends to all subjects, insisting this “principle can neither now nor at any future time be called into question.” Freedom to question, Callard replied with a smirk, apparently “extends to all subjects but one.”

None of this, of course, is easy or quickly understood.

Callard gets that. She seems to regard her everyday life as an extension of the struggle to get across big ideas in an approachable way. In graduate school at the University of Chicago, a fellow student once took her aside to say the class thought of her as a kind of crazy lady that nobody understood. “So I feel like since then I have gradually pulled myself up by the bootstraps of intelligibility to make myself more coherent to people.”

The second you step into her office you wonder if she’s overcompensating.

The room resembles the set of an aggressively cheerful children’s TV show. Colors and patterns explode in every corner. The door is covered in a Warhol-like repetition of Socrates faces; the blackboard is framed with more busts of Socrates. “Refute and Be Refuted” is scrawled in large block letters on the ceiling above an alcove. There’s a tree made of yarn. Lego castles climb walls. Keith Haring’s cartoon person dances along a wall. Callard enters wearing bright pink tights and a black dress covered in unicorns that, in a different decade, might have done double duty as a black-light poster.

When I attended one of her classes, she wore a striped dress and striped leggings that looked like a lesson in friendly clashing. She was teaching Descartes. It was the second class of the semester and she wrote in a corner of the blackboard: “Nothing is certain.”

A moment later, she scribbled: “Except this claim.”

She told her students, all freshmen, she was so excited to introduce them to Descartes. She bounced on the balls of her feet as she spoke, and when she spoke, she had a slightly vowely drawl suggesting she grew up on a surfboard in Southern California; when she talks on podcasts, listeners leave comments that she doesn’t sound like a professor or philosopher. The truth is she grew up in Hungary and then Lower Manhattan.

She notes that she sounds the same to everyone, regardless of who she is talking to. She doesn’t speak in different registers. She speaks to her kids the way she speaks to her students and her coworkers. Words tumble out and stack up and need a second to be spliced apart before they get replaced with a new pile of words. Her problem, she smiles, is “reconstituting the demand to be intelligible with the desire to be enthusiastic.”

More than a decade ago, she was diagnosed with autism. However, she said she is still so much “in the early stages of trying to understand it myself, it’s hard for me to say anything (about it) that isn’t me being pulled in by the gravitational force of some cliche.” Callard thinks she probably became a good teacher because “when you are teaching you tend to be very self-conscious about the question of how you are coming across.”

She’s spent a lifetime doing that.

She didn’t have many friends as a child. She read a lot of novels, “Because, what do humans do?” It was hard to feel like she was on the same page with anyone, she said. Her mother was an oncologist and her father was a lawyer, “and we left Hungary because of a lot of antisemitism and so much corruption.” They struggled in New York. She attended Orthodox Jewish schools, “which treated me and my sister as charity cases because we were the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. But we were not religious. Kids couldn’t come over since we didn’t keep kosher. My mom worried about me being indoctrinated: ‘Don’t worry how you do in religion classes — there is no God.’ The rabbi would say, ‘You are a smart girl, you need to study.’ I’d say it’s all fake, why bother?” She memorized Shel Silverstein poems because “children memorized poems in Hungary,” and when her teacher in New York asked her to write a poem, she wrote a Shel Silverstein poem. The teacher spoke to the class about plagiarism and called Callard’s mother. Her mother said they were jealous because American children are stupid. “Childhood was like that. I do the wrong thing then insist my way was just fine.”

One day in fifth grade, a popular girl sat with her at lunch and they became best friends. A year later, she asked her friend why she sat with her that day. “She told me she heard a rumor that after fifth grade, everything is reversed and the least popular kids suddenly become the most popular kids and she wanted to get in on the ground floor with me.”

Philosophy — which Callard said she initially studied via the philosophy shelf of a Barnes & Noble — presented her with a way of living, an ongoing conversation in which the challenge is being understood, maybe profoundly. To this day, with her own kids, dinner comes with a question: Should you ever lie? Would you rather fly or be invisible? Christmas dinner was served with a side of: Should you ever take revenge? Understanding, real thought, Callard said, happens best in person, socially, among people who disagree but are open to arriving at some kind of an answer.

What Socrates teaches us, she writes in “Open Socrates,” is that we only avoid ignorance by having the right kind of arguments with people who disagree — conversations in which those who are talking regard one another as equals, always pushing toward some truth.

Good luck with 2025, Socrates.

Callard has been studying how conversation works, how pauses happen, how people take turns. “Communicating without that structure is close to impossible for humans,” she said. “Yet it appears possible. Writing, for instance, is hard, it takes a long time to get good, realize what an audience might expect and so on. On social media, a bunch of people who can’t write try to communicate through writing. It’s a bunch of people walking around with eyes closed assuming when someone bumps into you, they’re evil.”

Socrates, Callard explains, believed that being understood happens when both sides of a conversation talk in good faith. “One of the things Socrates convinced me of was I don’t have opinions — I have words. I have an illusion of opinions and not until I get into conversation do I get to think about the questions.” You should not, for instance, move to Portugal, or Vermont, assuming everyone there would agree with you. Where people tend to agree is where you hear more honest conversations, revealing shades of agreement and disagreement. It’s probably true within your family.

“In a place where everyone seems to agree,” Callard said, “that’s where the real conversations might happen.” And yet Socrates, she said, thought that every argument is resolved.

It just takes more than five minutes in front of the Art Institute.

“Even among people who never agree, there can be hope,” Callard said. “When in life are you most often surprised? Conversations are when surprises most often happen. And because we can never eliminate the possibility of surprise, that means hope.”

Or as Socrates would put it, the only thing we shouldn’t do is remain as we are.

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com