To write a few words in remembrance of Jay Robert Nash seems insufficient, for this was a man for whom a few words were never enough. During his life, which ended on April 22 of lung cancer after 86 active years, he once estimated that he had written something in the neighborhood of 50 million words.

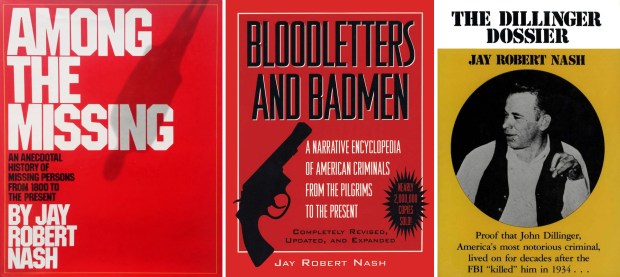

Most of those came in non-fiction books, firmly focused on crimes and killers (movies too), but he also wrote poetry and plays. Here is but a sampling of his 80-or-so book titles: “Bloodletters and Badmen”; “Darkest Hours”; “Hustlers and Con Men”; “Among the Missing”; “The Dillinger Dossier”; a multi-volume “The Motion Picture Guide”; “Encyclopedia Of Western Lawmen & Outlaws”; “Zanies: The World’s Greatest Eccentrics” and on and on.

Most of these books were created in the pre-internet age, when research was done the dusty old-fashioned way, plowing through archives and fading newspapers. Sometimes aided by a series of assistants such as Chicago researcher Jim Agnew, Nash was tireless. Late in life, he told me that his reference archives included nearly 500,000 books, three million text files and more than six million historical illustrations and photos.

Some of his books were big bestsellers and some were not. He made a lot of money. He lost a lot of money and borrowed plenty from friends. He won awards. He was always ready to file a lawsuit, as he did against CBS. He was sued by others.

As prolific as he was in print, he was equally loquacious in person, his personality and imagination cutting a story-packed path across the places where writers and journalists once gathered. Some of his stories were real, some were not but most all were unforgettable.

As writer Clarence Petersen put it in a Tribune story in 1981, “(Nash’s) most intriguing creation is himself. Pugnacious, diminutive, and dapper in the attire of a 1920s gangster, his heroic fantasies have made him a Chicago legend — especially among the patrons of his favorite saloons.”

In that same story, Roger Ebert said, “(Nash is) a legend builder. He lives in greatness, real or imagined, you never quite know. … When he’s out drinking, it’s as if Ernest Hemingway and Thomas Wolfe were at war for the possession of his soul.”

Jay Robert Nash III was born on Nov. 26, 1937 in Indianapolis, the son of Jay Robert Nast II and Jerrie Lynne (Kosur). His father was a newspaperman who went off to war and died in the Pacific in World War II. His mother, a cabaret singer in her youth, raised her son in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

After a couple of years of college at Marquette University, Nash then served with the Army Intelligence Corps of the United States Army in Paris for a couple of mid-1950s years and then attended — maybe — the University of Paris, graduating — maybe — with a bachelor’s degree in literature. It was there he said he “met” Hemingway, a writer he so admired that Papa became a frequent star in his many stories which included a wild one about how he helped bury the writer after his 1961 suicide in Ketchum, Idaho.

He started his career working for publications in Milwaukee, arriving in Chicago in about 1962 with the intention of “setting this town on fire,” as he then told my father, writer/newspaperman Herman Kogan, one of the first people he met here.

He revived for a year or so the Literary Times magazine started in the 1920s by one of his heroes, newspaperman Ben Hecht, and began wandering his way into the oases frequented by the city’s writers and journalists such as Mike Royko, Nelson Algren and Studs Terkel. Occasionally fists would fly, giving Nash a reputation as a barroom brawler. “We were all jerks,” Tribune columnist and novelist Bill Granger told Petersen. “Jay was pugnacious but, in retrospect, we were all obnoxious.”

I first met Nash through my father and a few years later, when I was old enough to frequent taverns, each of our encounters would begin with him shouting, “Kogan? Rick Kogan? You’re not half the man your father is.” But we hit it off, minus fists.

Forty-one years ago, he married a charming and smart attorney named Judy Anetsberger, now retired. “We met five years before we married,” she told me. “A lot of his so-called reputation was unfair. I have never known a smarter, kinder man nor one who worked harder.” They married in New Buffalo, Michigan, in 1983, where she had been raised and they later lived there for a while before the birth of their son. The son’s name is Jay Robert Nash IV, now 39 and a marketing executive living in North Carolina, with two-year-old Jay Robert Nash V.

“He was such a great father,” said Judy. “He loved going to baseball games with our son. It was a calmer life than the one he had known but he relished it.”

Marriage and fatherhood curtailed some of Nash’s nocturnal adventures as did the fact that some of his favorite haunts — Riccardo’s and O’Rourke’s — shuttered and some of his old pals retired, moved away or died.

Jeff Magill tended bar at the Billy Goat on Hubbard St. for three decades until retiring late in 2015. He remembers Nash fondly: “A bartender can only do so much to enliven the milieu. When Jay was in the room it was never a concern. He was self invented to such a degree that it came full circle, so unique as to secure a singular authenticity. Suffice it to say, I liked him very much.”

One person who knew Nash better and longer than most anyone is Bruce Elliott, the artist, writer, raconteur and proprietor of the venerable Old Town Alehouse, another of Nash’s favorite spots and the place he and Judy first laid eyes on one another. “Nobody in their right mind could ever accuse Jay of being boring,” he wrote in an online posting.

Though he tells me that he had not seen Nash for 20-some years, his memories remain fresh. In 2011 he wrote a series of stories about Nash on his lively blog, some of those stories making it into his own books.

Elliott and I talked earlier this week about Nash and I told him that Jay and I had been in touch last year, about his “new project” called “Secrets of the Cinema,” a series of print and radio pieces about “insider film information from and about international icons.”

We shared stories Nash had told us about his interviewing John Dillinger at an Arizona retirement home in the early 1970s and having fist fights on the streets of Paris with Hemingway. We laughed, even as we realized that we are part of a shrinking crowd of people who knew Jay Robert Nash, a fine writer, decent man and an authentic Chicago character.

rkogan@chicagotribune.com