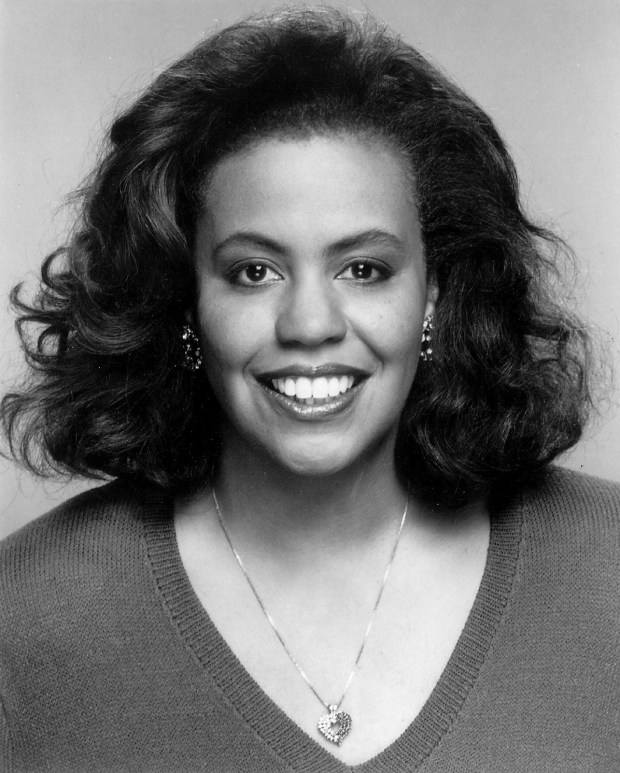

Renee Ferguson spent more than 25 years as a reporter on two Chicago television stations, and she made history as the first Black woman to work as an investigative reporter on TV in Chicago.

During her career, Ferguson, who also cofounded the Chicago chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists, established herself as one of Chicago’s premier investigative reporters, winning seven Chicago Emmy awards plus an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award for investigative reporting.

“Renee had this incredible ability to convince the powers that be in the newsroom to give her these really interesting assignments,” said former WBBM-Channel 2 director of community affairs Monroe Anderson, a longtime friend. “She knew how to work things out. She was really talented. And she was a good reporter.”

Ferguson, 75, died Friday while in home hospice care, said WMAQ-Channel 5 news anchor and reporter Marion Brooks, a close friend. She had been a longtime Chicago resident.

An Oklahoma native, Ferguson graduated in 1967 from Douglass High School in Oklahoma City. She then earned a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Indiana University in 1971.

“Renee and I were the only two Black students in the journalism department at Indiana University (at that time),” Anderson recalled.

After college, Ferguson worked as a writer for the Indianapolis Star before taking a job at a TV station, WLWI-TV, in Indianapolis in 1972. She spent five years at the station, which in 1976 took on the call letters WTHR-TV, and worked alongside a young, wisecracking weather forecaster named David Letterman, who would go on to national fame.

In 1977, Ferguson joined WBBM-Channel 2 as a reporter. While at the station, she drew national headlines for an investigative piece she reported that debunked the highly acclaimed Westside Preparatory School founder and teacher Marva Collins. By the late 1970s, Collins had become nationally recognized for her work, and Ferguson’s report threw cold water on that national praise, accusing the educator of lacking the background and temperament to teach and also alleging that Collins had not gotten the results she had said she was getting, and that she had used high-pressure techniques to collect tuition payments.

While at CBS 2, Ferguson also began hosting the public affairs talk show “Common Ground” in 1981.

“Renee always thought of herself as the voice of the voiceless,” said retired WMAQ-Channel 5 vice president of news and station manager Frank Whittaker, who first worked with Ferguson at Channel 2. “She would take on stories that nobody else would take on because she believed in what people were telling her and what she believed was the truth and she was going to be their voice.”

In 1983, Ferguson left Channel 2 to become an Atlanta-based network correspondent for CBS News.

WMAQ-Channel 5 hired Ferguson as an investigative reporter in 1987, bringing her back to Chicago.

“She really was so authentic and people trusted her and she had this uncanny ability to create a space that made people really open up to her. She had that sort of Oprah-esque vibe where people would just share with her,” Brooks said. “She also had great instincts — she knew when to follow the trail.”

One of Ferguson’s early reports was “Project Africa,” which was the product of an idea Ferguson had with a Near West Side elementary school principal in which they would bring nine children from Chicago’s toughest streets to Africa for two weeks.

The project required students wanting to take the trip to commit themselves to extra attendance both before and after school to study French, photography and West African culture.

“We did play tourist some of the time when we were in the cities, but by far the most moving times were when we visited the villages,” Ferguson told the Tribune’s Rick Kogan in 1989. “The native kids greeted the Chicago kids as if they were visiting royalty. It was an extremely special time for all the children. And I could see the Chicago kids getting more and more relaxed. They started out kind of shy, but as the trip progressed they began to feel surer of themselves. This is the sort of experience that will change them forever.”

In 1993, Ferguson visited strife-torn South Africa while on a prestigious William Benton Foundation Fellowship through the University of Chicago. She returned to NBC 5 afterward and covered the landmark 1994 elections in South Africa for the station. Later work included reports on strip searches of Black women at O’Hare International Airport, which in 1999 won Ferguson and her producer, Sarah Stolper, the Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award for investigative reporting.

“That was amazing work,” Brooks said.

In 1996, a young Chicago man, Tyrone Hood, was convicted of murder and armed robbery in the 1993 slaying of an Illinois Institute of Technology basketball star. Hood insisted that he had nothing to do with it, and Ferguson concluded that Hood was innocent and that another man had been the murderer.

Ferguson reported numerous stories about the case, all with Whittaker’s support. She continued that advocacy even after retiring, and eventually then-Gov. Pat Quinn commuted Hood’s lengthy prison sentence.

“Her work was able to get him out of prison,” Whittaker said. “She just really believed in helping when people reached out, and she had a true soul for it. It was ingrained in her.”

In the early 2000s, one of Ferguson’s investigative interns at Channel 5 was a Harvard University undergraduate named Pete Buttigieg. During Buttigieg’s internship, Ferguson and her husband housed the future U.S. Transportation Secretary and South Bend, Ind. mayor in their home.

“She was very proud that she was a mentor to Mayor Pete,” Anderson said.

Ferguson later was awarded a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University in 2007.

Ferguson retired from NBC 5 in 2008 and soon began working as a spokeswoman for former U.S. Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun during Moseley-Braun’s unsuccessful 2011 bid to become Chicago mayor. She later served as a press secretary for U.S. Rep. Bobby Rush.

Ferguson’s husband of 34 years, Ken Smikle, died in 2018. She is survived by a son, Jason Smikle.

Services are pending.

Goldsborough is a freelance reporter.