With more than five decades under its belt, Judas Priest is old enough to know the unwritten rules that make a memorable concert tick. That wisdom benefited everyone Wednesday at a packed Rosemont Theatre, where the band didn’t attempt to break down stylistic barriers or mount glitzy displays designed to go viral on social media. Sometimes, or especially in the ever-changing pop-culture landscape, nothing beats a classic.

With little left to prove except its contemporary relevance 55 years after forming in Britain, the group stuck to its hallmark techniques and zeroed in on what mattered: the music, and its iron-clad bond with the heavy-metal community. While many artists spout what the crowd wants to hear, then repeat the same banter in every city, Judas Priest spent scant time on talk and devoted its nearly non-stop 105-minute set to the proverbial walk.

In sound and vision, words and attitude, the quintet embodied the liberating release and unifying spirit of second-wave metal. For Judas Priest, that meant leaning into the sheer power of its craft, the outsider mentality of its lyrics and the occasional theatricality sparked by the pairing. The straightforward, hammer-down approach came across as both unapologetic and vintage — not to mention endangered in a modern era prone to solo stars and pricey, one-upmanship productions.

Led by vocalist Rob Halford, the band forged a thrilling assault that projected a defiant toughness that could withstand or defeat the challenges outlined in many of its narratives. Rugged, resilient and rebellious, the songs’ temperaments traced a direct line to the band’s origins in the industrial wastelands of Birmingham, England. As did the well-controlled aural cacophony that evoked all manner of steel manufacturing: pounded anvils, loud stamping machines and fire-stoked furnaces included.

Those parallels further assumed a visual form during “You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’,” a declarative anthem accompanied by black-and-white historical footage of workers laboring at a factory. And they adopted loaded meaning amid the back-and-forth sway of “Breaking the Law,” with Halford screeching “you don’t know what it’s like” akin to a desperate dreamer intent on doing anything to escape their soul-crushing circumstances.

Misfits, outsiders and blue-collar types standing throughout the venue understood exactly what he meant. Then again, Judas Priest has been speaking to and for those individuals since Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin were at their mid-’70s peak. Seldom concerned with mainstream trappings, Judas Priest’s dalliance with commercial fame in the ‘80s happened on its own terms.

Though the band never broke up — a feat that places it in rare company with the Rolling Stones and other select lifers — Halford’s exit in the early ‘90s triggered the start of a forgettable period that alienated everyone but diehards. The singer’s 2004 return led to a second-act renaissance that long ago surpassed the merit, longevity and productivity associated with most reunions.

Released in early March, the band’s 19th album, “Invisible Shield,” extends a run of strong studio LPs marred only by the conceptual “Nostradamus” (2008). It follows the group’s 2022 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; a pandemic-delayed 50th anniversary trek; and a bare-all Halford autobiography (“Confess”). Ironically, those positive developments owe to the type of lineup changes that often spell the end of bands.

In 2011, longtime member K.K. Downing suddenly quit over internal disagreements. In 2018, fellow guitarist Glenn Tipton, retired from live performance after the burden of dealing with Parkinson’s disease grew too difficult to bear. In their shoes stepped the relatively unknown Richie Faulkner and producer-musician Andy Sneap, respectively.

While purists may chafe at the replacements, each instrumentalist held up their end of the bargain from flanked positions on Wednesday. Rather than simply replicate passages, Faulkner and Sneap played with expressive license. The six-string fireworks that packed the spaces between the verses and chorus — pinched harmonics, squealing tritones, traded solos, doubled-up leads — erupted with a sharpness that matched the jaggedness of the main riffs.

While the latest recruits lacked the tight chemistry of their predecessors, Judas Priest’s rhythm section hurt for nothing. Bassist Ian Hill, the band’s longest-tenured member, stood in the shadows and operated as a silent lynchpin. Picking up on the resultant vibrations, he ensured the arrangements — even those that aimed at the jugular (the blitzing “Panic Attack,” the deep cut “Saints in Hell”) — remained tethered to a discernible groove. Hill’s partner, drummer Scott Travis, went another level beyond.

Entering his 35th year in the group, Travis put on a clinic. His combination of balance, solidity, timekeeping, force and steadiness bestowed Judas Priest with unshakable foundations and punchy dynamics. Travis’ four limbs navigated his double-bass kit with virtuosic ease. Cool and restrained, he avoided unnecessary flash such as splashy fills or busy cymbal crashes.

At times, the sustained crack of Travis’ drums resembled that of holes being bored into thick sheet metal. During a cover of Fleetwood Mac’s “The Green Manalishi (With the Two Prong Crown),” the rumbling percussive transformed into a fleet of approaching steamrollers.

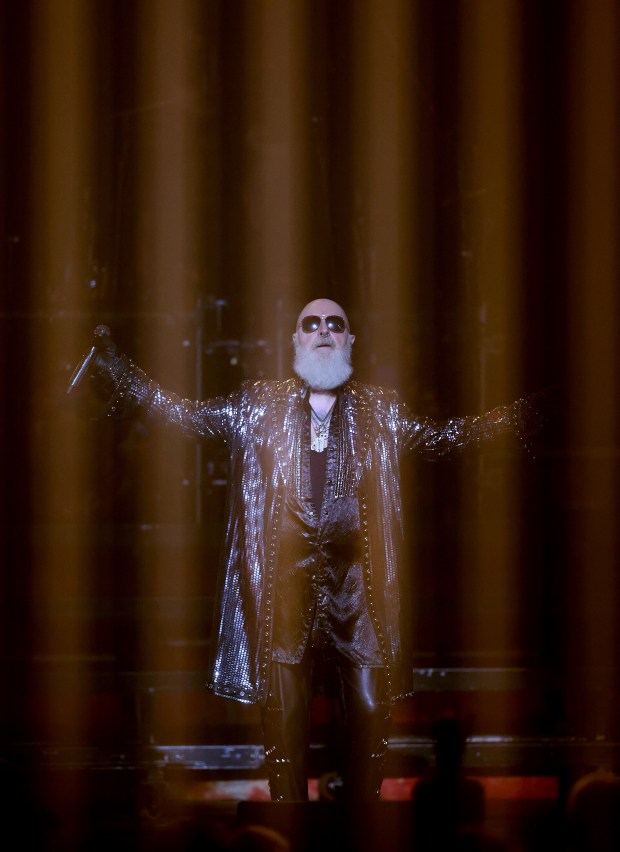

If Travis’ rolling thunder served as the rails on which the band rode, Halford’s multi-octave deliveries functioned as the high-speed train barreling down on tormentors and detractors. Unsurprisingly, the 72-year-old vocalist — who, with his big, fluffy white beard and shaved head could’ve passed for a character who walked right out of a Herman Melville novel — no longer possesses the near-infinite range of his glory days.

Yes, Halford hit shrieking highs and glass-shattering notes. But he limited their frequency and length, and received obvious assistance from reverb, echoes and loops. No matter. Few singers manage to cover as much territory. Fewer still strike a more commanding on-stage presence than the nicknamed Metal God, whose constant caged-lion pacing, demonstrative body language and cheerleading of his colleagues and crowd all ranked second to his impressive wardrobe.

Clad in black leather pants, boots and gloves, and cycling through an array of waist- and knee-length leather jackets dripping with studs, chains and tassels, Halford exemplified the heavy-metal biker demeanor Judas Priest practically invented. In addition to complementing the look of his mates, his clothing — which also included a floor-length denim battle vest that would’ve been ridiculous on anyone else — mirrored the fortitude and grit of the material.

Rotating through the roles of necromancer (the eerie “Love Bites”), exorcist (the vicious “Devil’s Child”) and pursuant (the sleek “Turbo Lover”) with resolute authority, the singer later found the fountain of youth while chronicling the triumphs of a heroic cyborg. Reaching upper-frequency extremes from a crouched stance, Halford and company’s unyielding rendition of “Painkiller” renewed the case for the song’s standing as the greatest metal composition of the past three-plus decades.

After that kind of exertion, who could blame the singer for sitting for a spell? Returning to the stage on a Harley-Davidson, riding crop in hand, Halford straddled the bike during the first half of “Hell Bent for Leather” before throwing one leg over the side and dismounting.

Just as expected. Judas Priest executed the signature move countless times in the past. Yet akin to the band’s unwavering commitment to blending heaviness with melody, some traditions never grow old.

Bob Gendron is a freelance critic.

Setlist from the Rosemont Theatre May 1:

“Panic Attack”

“You’ve Got Another Thing Comin’”

“Rapid Fire”

“Breaking the Law”

“Lightning Strike”

“Love Bites”

“Devil’s Child”

“Saints in Hell”

“Crown of Horns”

“Sinner”

“Turbo Lover”

“Invincible Shield”

“Victim of Changes”

“The Green Manalishi (With the Two Prong Crown)” (Fleetwood Mac cover)

“Painkiller”

Encore

“Electric Eye”

“Hell Bent for Leather”

“Living After Midnight”