After last Sunday’s rescue of two swimmers struggling at Porter Beach, the National Park Service is weighing whether to install more life rings at other beaches.

Indiana Dunes National Park spokesperson Bruce Rowe said life rings in weatherproof cases were placed at Porter Beach and Portage Lakefront and Riverwalk last year.

A new law taking effect July 1 requires the life rings to be located at entrances to public beaches along the Lake Michigan shoreline. State Sen. Rodney Pol, D-Chesterton, authored the legislation. Last year, the bill easily sailed through the Senate but was blocked in the House. This year, he was able to get it past the House and signed into law.

Pol is very familiar with Porter Beach. “I grew up out on that beach,” he said.

“I always hear about those drownings, and it was always a serious concern of mine,” Pol said.

During Pol’s first Senate session, Beverly Shores resident Carmen Hernandez approached him about getting life rings on Indiana’s Lake Michigan beaches. Illinois had just required them.

Hernandez’s sister nearly drowned, but her boyfriend wasn’t as lucky. Since then, the sister has become a huge advocate of beach safety and a volunteer with the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project.

Pol’s sister-in-law pushed him to try again this year to get the legislation passed. She’s a Portage police officer and dive team member.

“She had called me June 6 or 7 last year called and said, ‘I got a question. Where the hell are those life rings?’” Pol recounted. “I had to explain there was not enough support from the chair and some of the folks that were skeptical of it. Even though it passed with flying colors out of the Senate, that’s just the process. Sometimes things die and you don’t really get much of an explanation.

“She said, ‘You need to get your ***** back down there and get that bill passed.’ I asked why, and she said, ‘I just about drowned out in the lake looking for a young boy that unfortunately passed away.”

The boy’s grandfather didn’t have a cell phone with him, so he went to his house to call 911. “When my sister-in-law heard the call, she went straight to the beach. That’s where she found the grandfather. She just stripped down and got in the water.”

The water was cold and choppy. She started struggling right away, and she’s a very strong swimmer, Pol said. She found a little shoe floating in the water and ended up finding the boy up against the rocks.

“She was pretty pissed that we didn’t get that bill passed, so I had my marching orders after that,” Pol said. “It’s not just for the visitors but also our public safety officials out there as well.”

‘My son would be here today’

Pol estimates the total cost of installing the life rings in weatherproof cases at $100,000, with a cost of up to $1,000 for each life ring.

That pales in comparison to the $500,000 cost of a 24-hour search-and-rescue operation, he said. That kind of operation involves “getting a boat in the water and a bird in the air” to search for the body.

That’s just the financial equation. There’s also the value of saving lives, which is priceless.

Sharon Kenning knows this well. Her son, Tom Kenning, drowned while saving a girl at Porter Beach two years ago.

“I wish that life rings were there two years ago so my son would be here today,” she said.

Dave Benjamin, executive director of Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project, let Sharon know about the rescue last Sunday, telling her, “Tom saved two more lives.”

Tom’s death was an impetus for Pol’s legislation. Sharon recounted that tragedy from two years ago. “Honestly, had there been a life ring on that beach where there is one today, right across from where he drowned, he would be here today,” Sharon said. “He was literally inches from being able to grab that girl’s hand, and he kept inching out to try and get to her.”

“He’s standing waist-high on a sandbar, but he reached out far enough that he got sucked in and it cost him his life,” she said. Had that ring been available then, he could have used it, but there was nothing.

“My husband ran to the state park lifeguard chair looking for a life ring and there was nothing there and the lifeguards weren’t out because the beach was closed. But there was no red flag saying the beach was closed, so people were going in the water. The lifeguards were in the pavilion and they came running after my husband alerted them, but it was too late,” Sharon said.

“We want all of our public buildings to have fire extinguishers and AEDs and sprinkler systems in case there’s a fire or someone has a heart attack,” she said. “We invite people to our public beaches as part of tourism, and their guard is down because it’s beautiful and they want to have fun. What happens when something goes wrong? There’s nothing – nothing – to assist and we can’t wait for someone to come; it happens too fast.”

“My last words to my son were, ‘Don’t do it. You’re not a good enough swimmer.’ He thought he could go out waist-deep and actually reach her. He wasn’t swimming out to her; he thought he could reach her, and he went just a little too far. He got hit by a big wave, and that was the last we saw of him.”

Sharon, her husband, Tom’s 9-year-old daughter, his niece and nephew witnessed all of this, she said.

“It just seems like a no-brainer. Why aren’t we putting life rings on piers and public beaches that we’re inviting people to come to?”

Sunday’s rescue ‘went really well’

Porter Police Chief Todd Allen said a life ring had been placed at Porter Beach earlier, but it went missing. He suspects a winter storm may have taken it. The replacement is in a weatherproof case.

Last Sunday’s rescue “went really well,” he said. A police department Facebook post tells the dramatic story.

That evening, police were made aware of a possible drowning at Porter Beach. Lt. J. Holaway immediately noticed a life ring missing from its post. Beachgoers told him it was being used to rescue juveniles and directed him to them.

Friends said they saw a girl struggling in the water. Visitors banded together and pulled her to shore. While doing so, they saw another girl struggling in the water further west. While a boy ran to the life ring, one of the good Samaritans yelled for someone to call the police. The boy then ran back to the scene and handed the life ring to a man who swam toward the struggling swimmer.

The girl was about 50 yards from shore. While Holaway remained on the beach to direct additional emergency personnel, he saw the girl go underwater and resurface. Her rescuer tossed the life ring to her and pulled her to shore.

The girls were reunited with their parents and ultimately refused further treatment.

The life ring was purchased by the Porter Fire Department and installed by the Porter Street Department on May 24. This is the first time the life ring has been used since being installed.

Allen and Porter Fire Chief Jay Craig praised the beachgoers for their heroism and quick action.

Craig said even though the new law doesn’t go into effect until July 1, the town was proactive and installed a life ring last year.

“With Lake Michigan here, it’s a constant battle,” Allen said.

Donations helped pay for the life ring already installed and are encouraged for additional life rings, he said.

Pol hopes Homeland Security grants will be available for them as well.

He remembers swimming in Lake Michigan when he was younger. “The bigger the waves, the more fun they were. There were definitely some times where you get out there and you’d be just terrified. All of a sudden, you started feeling your feet pull from underneath you and you get freaked out because you go underwater and you don’t know what’s up and what’s down because you’ve been thrown around so much,” he said.

Beachgoers aware of safety

Beth Bentley, of Portsmouth, Ohio, was at Porter Beach on Wednesday with her children. The lake was calm. “They all know how to swim really well,” but she warned them to stay close just in case.

Katie Djuric, of Munster, was at Porter Beach with her kids as well. “I nearly drowned in Lake Michigan,” she said, during a cardiac event. “I don’t remember any of it, but my mom can tell you it was pretty scary.”

She’s cautious with her sons Luka, 10, and Novak, 7. “Hey guys, too far,” she yelled to them.

“I don’t let them get past the first sandbar,” she said, and if there are waves, they have to wear a flotation device like a life jacket.

“We haven’t had an incident. I try to keep them out of it.”

Toni Trombo, of Morrison, Illinois, is a newbie. “Actually, this is the first time I’ve ever been to the Great Lakes,” she said.

She knows firsthand about rip currents, however.

“In North Carolina, I got actually pulled in a rip tide, so I actually had to swim parallel to the shore,” she said. That was about 12 years ago.

“It had a lasting effect. I’ll be honest. I’m a strong swimmer, but I had trouble in that rip tide,” Trombo said.

Sara Firestone, of Porter, lives near the beach. “Always respect the lake,” she warned. “I’ve always known my boundaries and my limits.”

Her children, ages 3 and 2, have taken infant swimming lessons.

Flip, float, follow

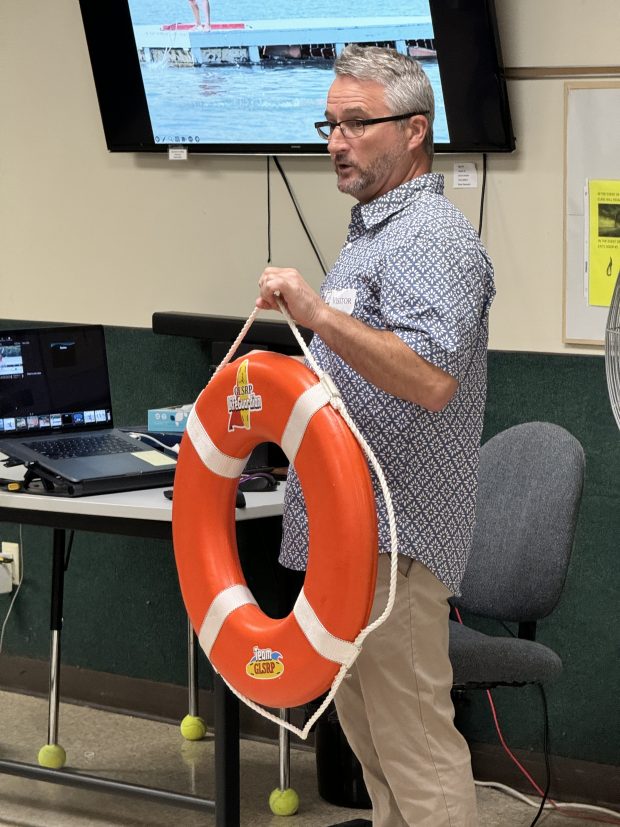

Benjamin, with the Great Lakes Rescue Project, spoke to the Kiwanis-sponsored Aktion Club at Opportunity Enterprises on Thursday.

“We now teach babies how to float before they learn to swim,” he said. “Floating is the most important water skill you can have.”

The OE clients knew what to do if their clothes catch fire – stop, drop and roll. That’s drilled into children. Fire drills are common at schools. So are tornado and active shooter drills. Some schools in Illinois and Indiana even do earthquake drills.

“There hasn’t been a fatal earthquake in my lifetime, but earthquake drills get more priority than water safety,” he said.

“Nobody plays in fire, but everyone knows a fire strategy like stop, drop and roll,” he said.

Millions of people play in the water, but do they know the water safety mantra? It’s flip, float, follow.

His organization promotes water safety and tracks drownings in the Great Lakes. Since 2010, there have been 1,268 drownings in the Great Lakes. In Lake Michigan alone this year, there have been 10 drownings.

The statistics are useful in knowing who’s more likely to drown. Benjamin said 80% of drowning victims are male. They’re more likely to take risks and to overestimate their abilities, he said.

Beachgoers should look for flags at the beach. Green means be careful even though waves are small. Yellow means be cautious because waves are higher. Red means stay out of the water.

Know the wind, too. A wind that blows toward the lake can quickly push you further from shore, especially if you’re on a floating object.

“Swimmers should stay with friends,” he said. That’s especially important because unless what you see in movies, drowning doesn’t involve a lot of arms waving and yelling for help. “Drowning is exhausting, and a person is gasping for air,” Benjamin said, so they can’t yell.

A person in the water, actively drowning, typically has their head tilted back, he said. “They need something that floats immediately. We need to toss them something that floats.”

Benjamin wants would-be rescuers to remember this advice: Reach, throw, don’t go.

He showed a video of surfers rescuing a swimmer in Grand Haven, Michigan. “These surfers, they know how to surf the waves, study the waves, they know how to use waves to their advantage.” The wet suit helps them float to the surface, too.

Benjamin spent an hour surfing at Portage Lakefront and Riverwalk Thursday afternoon before his speaking engagement at Opportunity Enterprises in Valparaiso.

Thirteen years ago, he said, he had a bad wipeout while surfing. “The waves pushed me to the bottom, and I immediately panicked,” Benjamin said. He was 40 years old.

“Knowing how to swim is just knowing how to swim,” he said. It isn’t knowing how to survive.

Flip onto your back, float to save your energy, follow directions from your rescuers.

Flip, float, follow.

Doug Ross is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.