Once hailed as Gary’s “showplace” and still the pride of its Black residents, the legacy of Means Manor and its developer Andrew Means won’t be forgotten.

Means became one of the most successful Black developers in the nation at a time when segregation divided neighborhoods and left Black families unable to buy homes.

The Alabama-born Means, who studied at the Tuskegee Institute under mentor Booker T. Washington, came to Gary with wife Katie and brother Geter Means in 1919 as part of the Great Migration. They founded the construction business with $90, in a tar paper shack on Broadway in 1922.

His crowning achievement is Means Manor, a Midtown subdivision of sturdy brick bungalows and mid-century modern ranch homes not far from Roosevelt High School, Gary’s designated school for Blacks. The brothers lived in their own ranch homes in the subdivision.

This month, the National Park Service approved an application placing the groundbreaking Midtown neighborhood of sturdy brick bungalows on the National Register of Historic Places.

“I’m very excited, happy and relieved it’s finally happening,” said Yejide Ekunkonye, who led the effort to gain the historic recognition. “It’s wonderful to bring more awareness to Mr. Means’ body of work and contributions to the city of Gary and to preserve his legacy.”

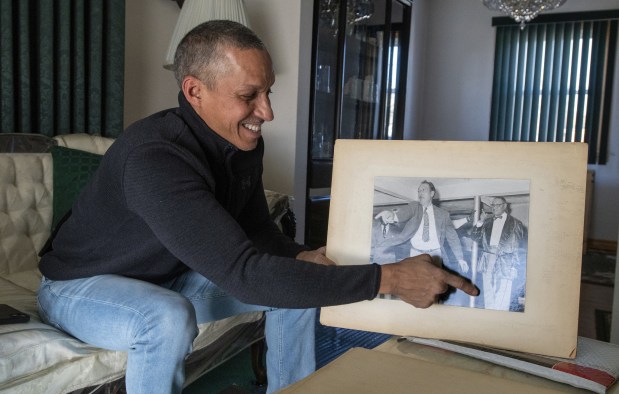

Everett McDonald points to his grandfather Andrew Means in an undated photo in Gary, Indiana Monday, November 21, 2022. McDonald’s grandfather, Andrew Means joined his brother Geter in founding the Means Brothers, at one time one of the largest Black-owned real estate development companies in the Midwest. (Andy Lavalley for the Post-Tribune)

Ekunkonye, whose grandparents lived in a Means Manor bungalow, rallied support to honor Andrew Means and launched a sayyestomeans.org website for former residents to share their memories and to enlist support in cleaning up vacant homes in the subdivision in partnership with Indiana Landmarks.

Blake Swihart, Northwest field director for Indiana Landmarks, said the National Register acceptance is an honorary designation and doesn’t impact how residents can upgrade their properties.

“It’s really a significant recognition to have one of few Black-owned and Black-designed neighborhoods maybe in the state,” said Swihart. “It’s a big deal.”

Means, who died in 1973 at age 80, built homes for Black families who lived in ramshackle housing in Gary’s segregated clusters. Means went a step further, though, issuing promissory notes to Black families denied loans from the Federal Housing Authority

With that trust, families took pride in their homes and the subdivision flourished.

Means’ new subdivision quickly became the preferred spot for middle-class Blacks in Gary. Priced between $12,000 to $75,000, Means plotted the homes on large, landscaped lots including driveways, sidewalks and winding tree-lined streets.

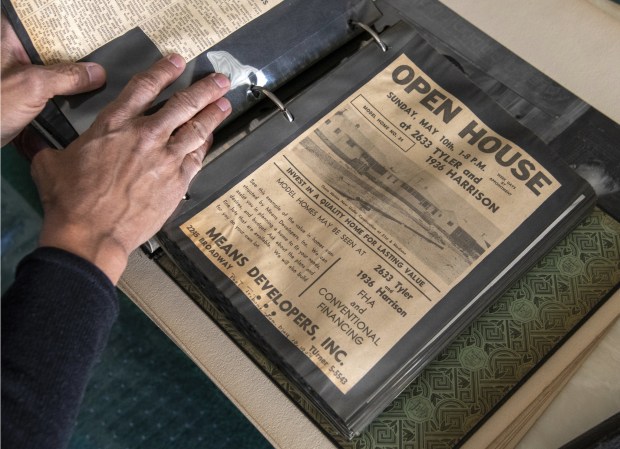

Everett McDonald looks over old news clips about Means Brothers Developers in Gary, Indiana Monday, November 21, 2022. The nearby home of Geter Means is on the Indiana Landmarks 10 Most Endangered list. (Andy Lavalley for the Post-Tribune)

By the 1950s, Means Brothers Construction ran two corporations, which netted more than $1 million.

Andrew and Katie Means became early civil rights pioneers in the city, as Andrew Means rose in civic stature, serving on the Gary Chamber of Commerce and several nonprofit boards. He attended a White House reception with the Kennedy family in 1963 and led a trade mission to Spain in 1965.

As segregation lingered, the couple placed their house on the Green Book, a travel guide for Blacks who were shunned by hotels for lodging. They hosted several traveling entertainers, including Josephine Baker.

His family estimated Means built about 2,000 homes and rental units in Gary. In 1962, he built the limestone gothic-revival-inspired First Baptist Church at 626 W. 21st Ave., just east of his own home.

In the future, organizers plan to erect a plaque memorializing the National Register honor, said Ekunkonye.

Geter Means’ house, built in 1954, is now at the center of an ongoing local conservation effort after it fell into disrepair. Indiana Landmarks purchased the home last year and later sold it to the Gary East Side Community Development Corp., a group that works to address workforce and housing needs.

“It’s a significant honor for Andrew and brother Geter and the neighborhood itself,” Swihart said of the new designation. “It represents great recognition of the neighborhood and what it meant to Gary at the time.”

Carole Carlson is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.