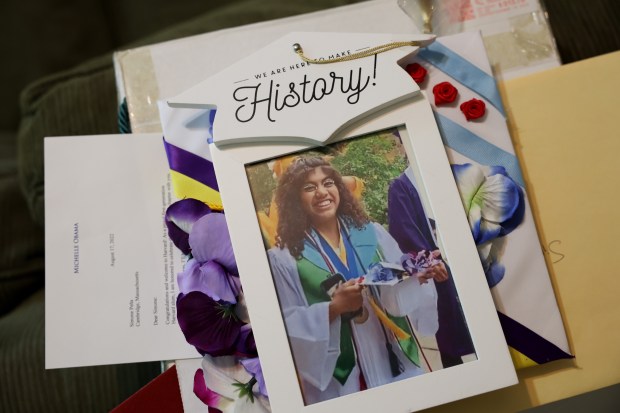

Simone Peña found out she had been accepted to Harvard with a full scholarship after school one day while she was getting ready to go clean houses with her parents, as she did most evenings and weekends. She recalled staring at the computer screen for a few minutes, unable to move or speak until her mother went to hug her.

“I got in,” she whispered to her mother. The three cried, celebrating a moment they never dreamed would be theirs. Then, they set out for their evening job, the family’s livelihood.

Amidst the mundane tasks of their cleaning routine, there was an undercurrent of triumph — a silent acknowledgment of the extraordinary journey they had undertaken together from Mexico to Chicago four years prior, when they decided to immigrate to the U.S., running away from cartel violence in their native town.

Now a rising junior at Harvard, Peña still returns home every school break to clean houses with her parents because she is repeatedly denied internships and other programs due to her immigration status. Even if she graduates with the highest honors from Harvard, as she did from Carl Schurz High School, she may never become the lawyer she wishes to be without the possibility of getting a job permit.

“I worry that my degree won’t be worth it,” Peña said.

Peña’s struggle casts a spotlight on the harsh realities faced by young undocumented immigrants in the United States and their parents. Without a job permit, her future and career dreams are threatened by bureaucratic red tape and political gridlock. Yet, amidst the uncertainty, advocates say her story serves as a beacon of hope for many, illuminating the urgent need for comprehensive immigration reform beyond temporary relief programs for recent asylum-seekers.

On June 7, Peña spoke among political and business leaders who gathered to champion the recent state resolution that calls for action from the White House to give work permits to longtime undocumented workers and more recent migrants alike. The group, once again, urged President Joe Biden to use his executive power to provide immigration reform, harshly criticizing his recent move to instead limit asylum claims at the U.S-Mexico border.

There, behind a podium and before dozens of people, she shared her story publicly for the first time. The sounds of clapping hands resonated through the room that cheered her on.

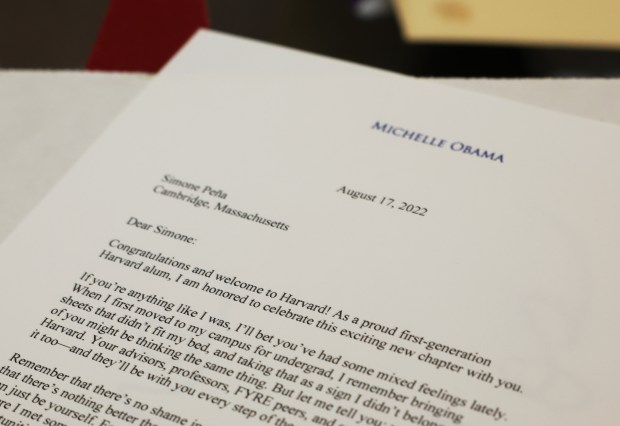

Though Peña had shared her immigration status with some of her mentors in high school, she mostly kept it a secret out of fear of jeopardizing her family’s safety, judgment and internalized shame, she said. But as she began to navigate life at Harvard, she faced roadblocks that led her to understand that she needed to make peace with her reality to empower her, rather than define her.

“I’m done living in the shadows. People like my parents and I deserve acknowledgment in this country. We deserve a chance to work legally in a country that we’re already contributing to,” she said.

Over the last two years, she has been turned away from campus jobs, fellowships, internships and other programs at Harvard because of her undocumented status. After every ‘no,’ she seeks her mother’s arms for comfort. When the two were thousands of miles away from each other, they would make do with a phone call.

“I tell her that God is bigger than us and that every ‘no’ will lead her to ‘yes.’ I tell her not to lose faith,” said her mother, Beatriz Hernández. “After all, she already made it this far.”

But “rejection is hard,” Peña said. “I’m young and I know I have time to figure it out. But what about my parents? My main concern is taking care of them.”

The family decided to leave their beloved Mexico six years ago after their patriarch, Epifanio Peña, lost his job, which caused them to lose their home. Aside from economic hardship, the cartel violence plaguing their region of Estado de Mexico spurred them on their journey north.

“It was the most difficult decision I’ve ever made, but my family’s well-being was more important,” said Epifanio Peña, a graduate of the prestigious National Autonomous University of Mexico and an accountant by profession.

Thanks to guidance from a friend who lived in Chicago, Epifanio Peña found a job in a construction company, a world away from his office job in Mexico. After a few months of working, he got an apartment for his family in the Irving Park neighborhood, where the family still lives now.

“Even though we knew it wasn’t going to be easy, I came here to work and make sure that my family was safe and that my daughters had a chance to pursue a higher education, and that’s what we’re doing, thanks to God,” Epifanio Peña said in Spanish.

Most evenings, after his full-time job as a construction worker, Epifanio Peña and his wife clean buildings and houses to make ends meet. For a few years, his wife worked as a parent mentor, tutoring students in need, but that was only until they requested a valid Social Security number, she said.

“My parents are my world. They have made so many sacrifices for me and my sister,” Peña said.

In Illinois, there are around 400,000 undocumented workers like Peña’s parents, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Most have been in the country an average of 15 years and the vast majority are Mexican immigrants and the working segment of the population contributes $1.5 billion in taxes per year.

In recent years the Biden administration has issued several programs to expedite temporary work authorization programs to recently arrived migrants, mostly from Venezuela, Cuba, Haiti and Nicaragua, in response to the sudden influx of migrants trekking to the U.S. But longtime undocumented immigrants, particularly Mexican immigrants, have been excluded even if they are fleeing similar situations, said Erendira Rendón, vice president of immigrant justice at The Resurrection Project.

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals has also been stalled, battling its legality in the courts, leaving thousands of young immigrants in limbo.

“It’s a paradox that Peña is accepted in one of the most prestigious institutions in the world, yet she could be deported any moment. Or that once she graduates, she may not ever be able to get a job,” Rendón said. “It’s absurd that people like Peña and her parents are not considered when making decisions about immigrants in this country.”

Rendón, who is a DACA recipient, began to push the ‘Work Permits For All’ campaign last year, frustrated by a system that has not provided relief for more than 11 million undocumented people in the country since the Reagan amnesty in 1986. While Rendón led the efforts to help new migrants apply for temporary protected status and expedited work permits, she felt as though her parents were being left behind.

Work Permits for All is a campaign that mobilized mixed-status families, young immigrants left out of DACA, community-based organizations, businesses and faith leaders. It called on President Biden to authorize the establishment of a parole and work authorization program for long-term immigrant workers.

The movement, now a state resolution with overwhelming bipartisan support, has pushed the immigration debate before Biden as the election approaches. On Tuesday, Biden is expected to announce a new executive action that would shield certain undocumented immigrants living in the United States from deportation and provide work permits, according to reports.

Peña is part of a population of “forgotten Dreamers,” young undocumented people who now once again live in the shadows and are discouraged from pursuing higher education because even if they do, they may never be able to work in their field legally. Her story, Rendón said, reflects the diversity and complexity of the undocumented community and it highlights the need for Biden to provide comprehensive relief and “work permits for all,” not just new arrivals or asylum-seekers from certain countries.

In Illinois, there are around 20,000 undocumented students in higher education, according to the Higher Ed Immigration Portal.

U.S. Rep. Delia Ramírez, a Democrat from Chicago, said that Simone Peña gave her a butterfly pin, an icon of migration that she took to Washington, D.C., with her and it is a constant reminder of why she is in Congress.

“In the absence of congressional action, no real work done since 1986, when parent became citizen, that we call onto President Biden to do what other presidents in 30 years have not done, which is issue, boldly, proudly, unapologetically, work permits for all,” Ramírez said during the news conference.

Peña stood bend Ramírez and several other city and state officials who vowed to make immigration a priority at the Democratic National Convention.

Though she was afraid of what could happen after sharing her story, a sense of relief took over, too, she said. She hopes to inspire her younger sister, Zianya, who is 15.

“I’m surrounded by people who make me believe that there are opportunities out there for me,” she said. This summer she will be interning with the American Business Immigration Coalition and The Resurrection Project. Her first internship since starting her college career.

Their faith, Epifanio Peña said, is what keeps him and his family strong and resilient despite the constant roadblocks of not having a Social Security number or protection from deportation.

“We are so proud of her and we are faithful that everything will be worth it,” he said.

The matriarch, Beatriz Hernández, prays every day that somehow, one day, Peña’s dreams can go beyond Harvard.