Daunted by child care costs, Kamaria Noble initially wasn’t certain she’d be able to graduate high school following the birth of her son. At best, the Auburn Gresham teen had hoped to find an alternative school she could attend part time, in order to work.

Instead, Noble’s research led her to Chicago Public Schools’ Simpson Academy for Young Women, a Near West Side school devoted to pregnant and parenting students that she and classmates credit with helping them to thrive amid the challenge of attending high school as new moms.

After graduating from Simpson this spring, Noble will be headed to the University of IllinoisChicago in the fall to study education. “When I was pregnant before I came to Simpson, I didn’t know if I was going to be able to do it … and now I feel proud of myself for getting to this point and I feel grateful,” she said.

Federal law protects pregnant and parenting public school students’ right to remain at their existing schools. But, students who spoke to the Tribune said they felt stigmatized at their former high schools and opted to transfer to Simpson.

A 2018 study conducted by the organization Child Trends found that nationally, almost half of women in their 20s who gave birth in their teens dropped out of school. At Simpson Academy, the dropout rate in the 2017-18 school year was 26% and has declined every year since, with the exception of 2021-22. Just 11% of pregnant or parenting students left Simpson during the 2022-23 school year, the most recent for which CPS data is available.

That’s not for lack of trying, according to experts who note that having a child tends to compel teen moms to strive hard to finish school. A 2023 Journal of Higher Education Policy and Leadership Studies report found their efforts are often “foiled” by the lack of child care and supportive environment that students said Simpson provides.

Along with the demands of work and child care, social stigma often influences young moms’ decisions to drop out, the authors note.

Teen pregnancies hit a record low in 2023 according to data from the National Center for Health Statistics. But “disparaging” attitudes toward teen moms abound, according to psychiatrist and researcher on adolescent pregnancy, Jean Wittenberg.

“Around the world, there is stigma against these young women … and hurdles that we create for them, because of how we see them,” he said, noting research on young moms often debunks “inaccurate and damaging beliefs” about them.

Noble said judgment was among her initial concerns upon becoming pregnant while attending Simeon Career Academy. After seeing pregnant students before her ostracized, she said she opted to hide her pregnancy. Noble gave birth over a winter break and then transferred to Simpson. But she wasn’t able to sidestep what Wittenberg calls his biggest concern: Negative reactions to teen moms that he said pervade health care.

“Sometimes I felt kind of forced into things. I would ask questions, but it wasn’t clear, wasn’t thorough,” Noble said of health care providers’ responses. After learning about the disproportionately high maternal mortality rate among Black women, she said the experience — and Simpson’s contrasting culture — have stuck with her.

“Once you become a teen mom, you don’t receive that much love. You don’t receive that much care or attention – people just kind of push you to the side – and at Simpson it’s the total opposite,” said Noble.

‘There’s never an opportunity to fail’

Aide Ortiz Bahena said she was in the process of dropping out of Kelly High School upon learning about Simpson.

During a high-risk pregnancy, Ortiz Bahena said she wasn’t allowed to use the school elevator. “I would get really dizzy, so I stopped attending and that was worrying me,” she said. But after the birth of her son, Ortiz Bahena was more anxious about leaving him in daycare than taking a break from school. She’d returned to Kelly only to submit dropout paperwork when a counselor told her about Simpson. Educators at Simpson allowed her to periodically look in on her son at the onsite day care, so that she could become more comfortable focusing on her studies.

She plans to pursue a nursing degree at Malcolm X College in the fall. “I feel happy that I’m finally done with high school, but sad that I’m leaving Simpson,” Ortiz Bahena said. “This is my safe space.”

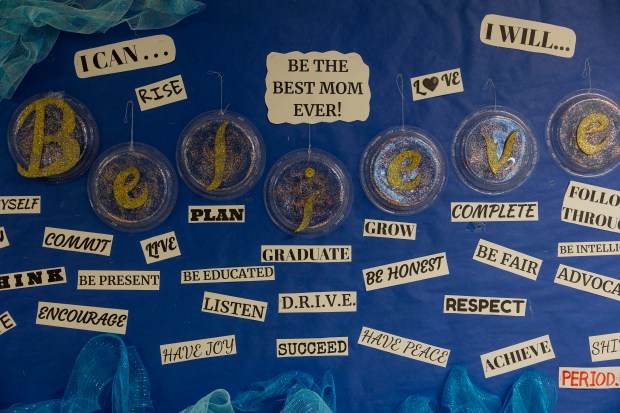

School days at Simpson are designed to ensure student success, said Principal Sherita Carter-King. “We’re really trying to catch them, make sure that there’s never an opportunity to fail,” said Carter-King. She said a block of time every other week is devoted to academic intervention, which entails working one-on-one with students in subjects in which they’re struggling.

Rising junior Ashley Zapata recently transferred to Simpson from Little Village High School, where her grades fell as chronic nausea arose. She said she remains “shocked” seeing teachers work with students on an individual basis — and grant them pregnancy and breastfeeding-related accommodations outright. “I wouldn’t get that support at my other school,” she said. “They try to make students feel more comfortable,” Zapata said of Simpson educators.

But not so comfortable that they fall asleep, said Carter-King, noting that sleep deprivation is a challenge parents of newborns face regardless of age. She said she’s seen students transfer to Simpson and, despite pushing themselves to do well, doze off in class. “We try to build some strategies in place — go take a walk, grab some water, take a 5 minute break, come back — and then in the classroom, build in activities that don’t allow for sleep. Movement, some media, small chunks of things versus a long lecture,” she said.

Rising senior Shaniyah Conley said she participates in class like never before, thanks to Simpson’s calm environment. “There was just fights every day at school. I had to get away from that,” she said of transferring from Julian High School. “At this school, I’m actually doing my work. I’m actually listening, asking for help, asking any questions necessary. I have a voice here … everyone has a voice here. Nobody is mistreated. No fighting. No bad drama. It’s all good vibes here,” Conley said.

Her 2-year-old daughter doesn’t always share Conley’s enthusiasm. “She doesn’t like waking up in the mornings. But her mood changes when we get to school,” Conley said.

‘Everybody needs help’

Multiple students noted how they’ve grown in caring for their children.

“Sometimes it is hard handling a baby. But after you get to know them, it gets easier. The love that you share with them — it’s a lot,” said rising junior Rosario Catinac, whose son is a year and a half. One thing she said he’s taught her: “Even though sometimes you feel like you can’t handle a situation, you can learn how to handle it.”

Catinac said she’s grateful for her mom’s support while in school but aims not to need it in the future. “What I envision for myself is having a career, having a stable job for me and him, so we don’t have to ask for help from anyone,” she said.

That’s a common trait among Simpson students, said Noble, one of the recent graduates. “A lot of teen moms, and sometimes myself, don’t like to ask for help. Because people will just say, ‘You should have never had the baby if you couldn’t take care of it by yourself, if you need help.’” She continued, “But everybody needs help no matter how old you are. You have a child, you’re going to need help.”

The support extended to teen moms — or not — is pivotal to mother and child, said Wittenberg, the psychiatrist and researcher. Teen moms tend to come from disadvantaged backgrounds and over the long term, do better than their peers, he said. “They turn their lives around as a result of having babies. … But they don’t end up doing as well as they could and some moms fail because of stigma, who might otherwise have succeeded if they had been supported,” Wittenberg said.

“Because the kids have to go through these tough times in the first years of their lives, they don’t do as well as they might do in the future,” he added.

He said he’s flummoxed when thinking about solutions. “How do you make people look at other people and see them as people with potential and dignity and deserving of respect and with something to contribute,” Wittenberg said.

For their part, recent Simpson graduates Noble and Ortiz Bahena aim to create for others the type of maternity and labor experiences they wish they’d had.

“I would love to help young moms,” said Ortiz Bahena, who hopes to specialize in postpartum care as a nurse. “Sometimes when they go to the hospital, people just ignore them and think that they don’t have a say because they’re teenagers.”

In addition to becoming an early childhood education teacher in Chicago Public Schools — as part of the district’s Teach Chicago Tomorrow pipeline program — Noble aims to become a doula, or birthing assistant. “I want to be a person that can advocate for my clients so that they never feel like they’re going into something blind, or they’re doing something that they don’t really want to do or don’t really understand,” she said.

In the meanwhile, she and other students encourage teen moms to keep their dreams alive. “Don’t think your kid is holding you back from achieving your goals. If anything, see it as a motivation, for your kid, to be able to achieve even more,” Ortiz Bahena said.