The headline 105 years ago read, “Dead, dying litter Hammond Street.”

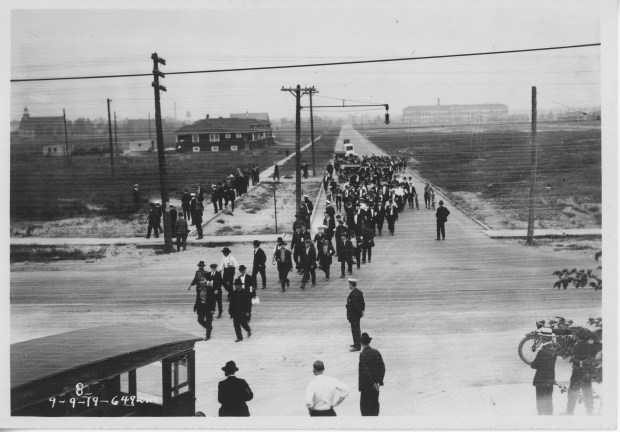

On Sept. 9, 1919, four men were killed and 64 were injured after police and security guards fired shots into a striking crowd where Columbia Avenue and Highland Street intersect in Hammond.

The article published the same day of the shooting described a scene where the bodies of the injured and deceased lay on Highland Street and “dotted” the open prairie to the north.

Wawrzyniec Dubeck was a 32-year-old automobile builder; Stefan Krawczek was a 38-year-old laborer with six children; Jerzy Rozka was a 50-year-old worker and Stanislaw Skis; was a 34-year-old blacksmith. They lived with their wives and families in the company houses that lined the area, some still standing.

On Sept. 14, floral wreaths were laid down on a new granite memorial dedicated to the four men and the historic event of the Standard Steel Company Strike, outside of the Ophelia Steen Center at 5927 Columbia Ave.

“Now these four men can rest in peace, so we can rest in peace,” said Terry Steagall, a retired employee of Inland Steel Company. “This makes younger generations know of what happened, what these people stood for. And that struggle goes on, which is why we need to fight economic injustice. We don’t want to go back.”

The dedication ceremony included historians from the Hammond Historical Society, local union members and region leaders like U.S. Rep. Frank Mrvan Jr., former U.S. Rep. Pete Visclosky and State Rep. Carolyn Jackson. John Wachala and David Detmer played historical union songs.

Mrvan said the Hammond strike was one of many across the nation that fought for workers’ rights during that time.

“It took from 1919 to 1938 to have the Wagner Act, a federal law that allowed individuals to picket and be able to strike for what they believe in,” Mrvan said. “So many individuals gave their lives — almost a total of 50 to 60 during those strikes.”

Loretta Tyler, United Steelworkers District 7 assistant director, said she grew up in Hammond and never knew the history of her neighborhood until she learned of the Standard Steel Car Company.

“Those in power have always pitted us against each other,” Tyler said. “They rely on prejudices, jealousness and ignorance to control working people. Even though the strike did not completely achieve the results the workers looked for, it showed that unity and solidarity is our strongest weapon against greed.”

In the aftermath of the shooting at the strike, Indiana Governor J.P. Goodrich commended the officers, stating “Force is the only way to obtain law enforcement under the circumstances.”

Newspapers of the time painted a picture of outside radicals and immigrant agitators, with headlines such as: “Hundreds of rioting aliens attack police this A.M.,” and “Officers defied by alien strikers.” At the time, many of the immigrants who worked and populated the East Hammond area were from Russia, Poland, Germany, Slavic countries and other parts of Europe.

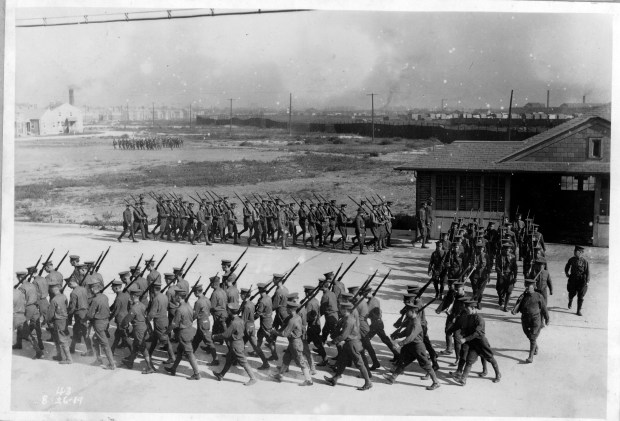

In reality, historians said the strike was the boiling point of a long, tense stand-off between the Standard Steel Car Company and those who labored for it. Hundreds of people of more than 20 nationalities were a part of the strike, advocating for an eight-hour work day, safer working conditions, adequate living conditions, recognition as a union and a raise from 42 cents to 52 cents.

According to historical accounts, tensions among strikers and authorities rose on the day of the shooting, in which police and company guards worked to disband the group of strikers who were trying to stop strike-breakers from entering the building.

Many people were interviewed in the subsequent investigation, in which a company guard said the shots began immediately after he used his shotgun’s butt end to strike a pistol out of another man’s grasp. About 100 shots were fired at the crowd, reports said.

The project to create a memorial began with the book “Strike!” by Patricia Goreman. It inspired Ruth Mores, of the Hammond Historical Society, to seek out the resting sites of the four men who were killed.

They were buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in Calumet City without headstones in the “pauper section” along the cemetery’s edge. However, when Burnham Avenue was widened in 1940, they were relocated. When she tried to track down their final resting place, nobody knew.

“I even went as high as the highest Catholic priest who was in charge of the Chicago area cemeteries, and he could still not find documentation on where they had been moved to,” Mores said.

“He said, ‘Remember in the 1940’s, handwritten cards were used to identify locations of graves.’ But this was 2019 when we were searching for them, and he still could not give us answers. So the Hammond Historical Society decided to put a monument to the four men in Indiana where they lost their lives, at Highland and Columbia.”

The United Steelworkers and the late Tom Conway, a United Steelworkers leader, donated much of the funds that made the monument possible.

Tom Novak, president of the Hammond Historical Society, said the organization is still fundraising to do further landscaping, historical markers and more at the site.

“It took over a century to get this physical reminder, this granite stone, that they deserve,” Novak said. “…These men didn’t exist in a vacuum 105 years ago. We must understand the context of the time to understand how things reached a crescendo of violence and senseless deaths.”

The plant and much of the century-old buildings still stand today north of 165th Street, at an industrial site now known as Jupiter Aluminum, Novak said.

“The men who worked at Standard Steel Car Company worked in hard conditions within the plant itself,” Novak said.

“Outside of it, the company tenement housing did not have hot water and drinking water was often gotten from hydrants outside. Nine to 12 hour days were standard, and often double shifts and working late into the night would be required if ordered, which sometimes amounted to dozens of train cars a day.”

He asked the crowd at the ceremony, “Would you today put up with working 50 to 60 hours a week with no overtime pay? Would you put up with unnecessarily dangerous working conditions?… And this one I thought was interesting: Would you put up with your manager demanding you share part of your paycheck so he can save up to buy a car for himself?”

The “No’s” resounded loudly.

“These are the kinds of things that were happening at Standard Steel Car Company. So thank these men today for why you don’t have to ponder these questions in 2024,” Novak said.

In her speech, Jackson paralleled the struggles of the past to those of today, citing a current decline of union power in Indiana.

“Fast-forward to today as we see echoes of those same struggles,” Jackson said. “The high cost of living remains a challenge for many, with wages that have failed to keep pace with the prices of many of our essential goods and services. Real wage growth has been stagnant while workers’ productivity has skyrocketed. And yet our workers are being asked to do more and more for less and less.”

Anna Ortiz is a freelance reporter for the Post-Tribune.