In a time of ferocious partisanship, Americans can be grateful to see Republicans and Democrats agreeing on something important: the scandalous abuse of the president’s pardon power.

Alas, the two parties disagree on which pardons deserve condemnation — with Republicans furious at Joe Biden for giving his son a free pass and Democrats outraged by Donald Trump’s past and potential clemency. But maybe their anger will open some eyes to the perennial danger of vesting such unchecked authority in one person.

Biden’s decision, breaking a staunch pre-election promise, brings to mind what Lily Tomlin said: “No matter how cynical you get, it is impossible to keep up.” Pardons breed cynicism in the same way that corpses breed maggots.

We generally revere the framers of the Constitution as incomparably wise. But they were capable of major blunders.

I refer not to their refusal to treat women and Blacks as full citizens, which was a deliberate choice, not an inadvertent error.

They made such a mess of the presidential election process that an amendment was needed just 16 years after the Constitution came into effect.

They included no provision to replace the vice president after a president dies. They left a lot of vital questions unanswered, such as whether Congress’ exclusive power to declare war includes the exclusive power to start wars.

But giving the president the right to nullify any federal conviction or punishment turns out to be equally short-sighted. It’s a vestige of monarchy that has turned out to be about as trustworthy as rule by divine right.

Hunter Biden’s escape is a conspicuous example of presidents perverting this authority for personal ends. But on the list of worst pardons, it would land near the bottom.

Set aside Gerald Ford’s pardon of Richard Nixon, which history has treated kindly. Harry Truman showed mercy to felonious Democratic politicians. George H.W. Bush spared several Reagan administration officials for their role in selling weapons to Iran — officials who might have implicated Bush himself in serious crimes.

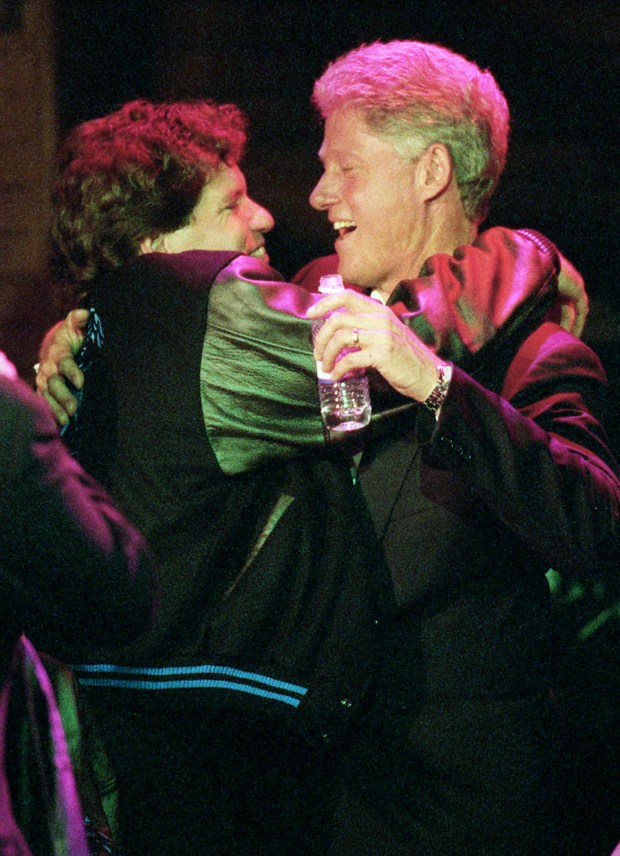

Bill Clinton pardoned his half-brother Roger, a drug dealer. He did the same for Marc Rich, a wealthy fugitive whose wife, by the oddest of coincidences, had donated $450,000 to his presidential library. Nixon granted amnesty to Teamsters union President Jimmy Hoffa, which surely had nothing to do with the union’s endorsement of Nixon in 1972.

Then there is Trump, who indulged a squadron of sleazeballs, including Rod Blagojevich, Dinesh D’Souza, Joe Arpaio, Steve Bannon and Roger Stone — not to mention Charles Kushner, his choice for ambassador to France. That’s before he keeps his vow to protect Jan. 6 insurrectionists from the consequences of their crimes.

The framers unintentionally facilitated these abuses by awarding the president unilateral authority to overturn the decisions of criminal courts. Virginia’s George Mason, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, opposed the provision for fear the president “may frequently pardon crimes which were advised by himself.”

James Madison, chief author of the Constitution, dismissed worries about a president abusing the pardon power. After all, he argued, “the House of Representatives can impeach him; they can remove him if found guilty.”

I’ll pause to let you finish laughing. Presidents habitually evade accountability by waiting until their final days in office to carry out their most sordid acts, putting them beyond the reach of the legislative branch.

Besides, Congress has effectively nullified the impeachment clause. Given that Trump couldn’t be convicted of high crimes and misdemeanors even after inciting and enabling the Jan. 6 attack on democracy, it’s hard to believe that any president will tremble at the threat.

On top of that, the Supreme Court has cheerfully invited the president to do his worst. In a July decision, it decided that the president is entitled to “absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within his conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority” — which, the court said, includes pardons.

Thanks to this bizarre ruling, a president could order aides to engage in massive violations of the laws and the Constitution, while promising to pardon them. And no court could make the aides, or the president, pay for such crimes.

There is much to be said for correcting miscarriages of justice or extending mercy to criminals who have reformed. But lately, it’s not at all clear that the good pardons outweigh the bad ones.

The framers could have constrained the executive by allowing Congress to override pardons, which would leave most cases of compassionate clemency alone. Or they could have required Congress to approve each one. Or they could have decided to relegate the pardon power, like King George III, to the landfill of history.

Instead, they conferred on the president an authority that serves as the definitive proof of Lord Acton’s dictum: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

Steve Chapman was a member of the Tribune Editorial Board from 1981 to 2021. His columns, exclusive to the Tribune, now appear the first week of every month. He can be reached at stephenjchapman@icloud.com.

Submit a letter, of no more than 400 words, to the editor here or email letters@chicagotribune.com.