Time doesn’t change much for Teresa Weatherspoon and Becky Hammon.

It has been 21 years since they wore the same jersey for the New York Liberty. In those years, Weatherspoon and Hammon formed part of a tight-knit fraternity of former WNBA players who have returned to the league as coaches. They also represent a new wave of women rising from assistant coaching positions in the NBA to head coaching roles in the WNBA, a crucial pipeline for talent development between the leagues.

But when they stepped into Wintrust Arena for Thursday’s game between Hammon’s Las Vegas Aces and Weatherspoon’s Chicago Sky, none of those milestones mattered. They were just two ex-teammates catching up after a long break.

“That’s my little sister,” Weatherspoon said as the pair sat down to hold a pregame news conference together.

“I like to see her before I have to go out there and see her pumping her fist in my face again,” Hammon joked.

The joint news conference was a nod to their routine during the three years when Hammon worked as an assistant coach for the San Antonio Spurs and Weatherspoon for the New Orleans Pelicans. When the teams played one another, Weatherspoon would slip into the Spurs locker room before tipoff to trade stories with Hammon.

In a friendship spanning nearly three decades, this is how they’ve always been: catching time between games, slipping back into conversation with an immediacy built on mutual respect.

“She was my first vet,” Hammon said. “So now to be sitting across from her — I know we’ve always been cheering from afar. I don’t talk to her every day, but we pick up right where we left off. I don’t need to call her and be like, ‘Spoon, are we still cool? You still got me?’ I already know.”

Hammon remembers her first impression of Weatherspoon during her rookie year with the Liberty in 1999: “Man, I hope I’m that comfortable in my skin when I get older.”

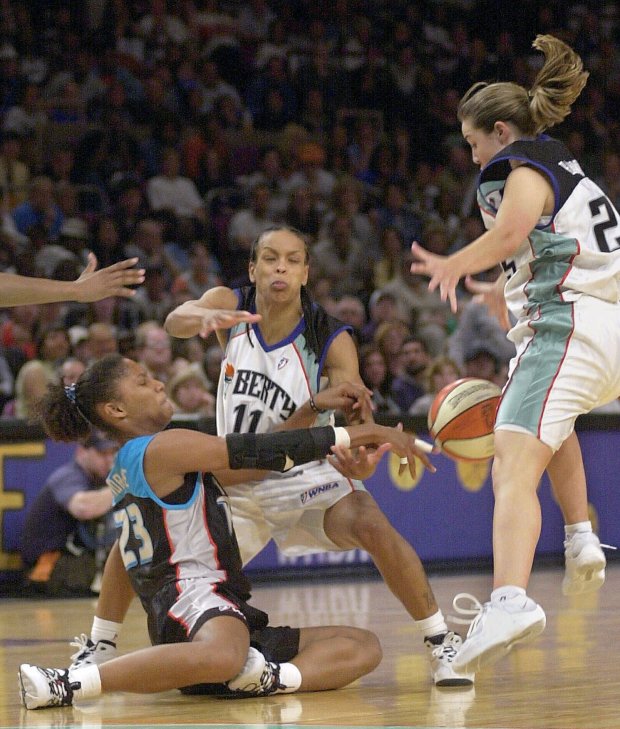

Weatherspoon had been on the Liberty roster since the league’s inception two years earlier, and she was a nine-year veteran of the toughest leagues in Europe. When Hammon showed up, it was Weatherspoon’s job to put the rookie through her paces.

“If it was happening nowadays, it wouldn’t be good,” Weatherspoon said.

“It would be called hazing,” Hammon interjected with a laugh. “Back then it was just called, ‘Let’s see if you’re tough.’”

Two weeks of that treatment — call it hazing, call it rookie duties — earned Hammon a reputation she would carry throughout the rest of her career, first as a player, then as a coach.

“We wanted to see if this one owned a towel to throw in,” Weatherspoon said. “Because we don’t own towels to throw in. And she knows that. Never did she give in. Never did she stay down. Every time she hit the floor, she got up.”

It’s hard to imagine a version of Hammon that didn’t speak her mind. But 25 years ago, that was the version that showed up in New York after going undrafted out of Colorado State.

Hammon still was informed by her upbringing in Rapid City, S.D. Her environment back home was conservative and expectations were restrictive.

“Women, girls, if you didn’t like it, you just had to sit there and shut up and kind of choke it down,” Hammon said. “You didn’t really speak up.”

New York, the WNBA and teammates such as Weatherspoon represented a different version of being a woman — one that was loud and tough and strong before anything else.

“As a young player, in a generation that did want you to sit back and be quiet, her generation pushed,” Hammon said of Weatherspoon. “And they did not sit back and be quiet. And this is why this generation now has voices that they never had. It’s because of that.”

Watching one another from opposite benches Thursday, Weatherspoon said she still could see that younger version of Hammon, whom she nicknamed “Ham Hock” as a rookie — bangs hanging halfway down her forehead, voice a little softer, competitive fire burning the same.

“Just a little baby girl,” Weatherspoon joked.

In the same way, Hammon and Weatherspoon see themselves in the 2024 rookie class that once again is transforming the WNBA. It’s the same fire, the same desire, with a little more brashness — and a whole lot more attention.

“At the end of the day, they’re really super skilled, they’re fun to watch — and they’re jawing at each other,” Hammon said. “People like to be like, ‘Oh, Angel (Reese) is talking.’ I’m like, nobody talks more crap than Caitlin (Clark) too.’ … It’s a different generation. I think we talk subtly. They be talking in your face. And my thing is — let them go. They’re big girls.”

Both coaches find it hard to understand the discourse around in-game civility in the WNBA. They remember themselves as players, eager to talk trash and step to an opponent.

Even now, Hammon and Weatherspoon rarely back down from a conflict, encouraging their players to bring their personalities onto the court.

“Why hold back?” Weatherspoon said. “I mean, I’ll be honest, I jaw too. Like (Hammon) said, if you went after one of my teammates, you definitely going to come through me. And I’m jawing.

“Because we want to win. Why not? What are you holding back for? There’s no tomorrow. You’re not out there to harm anyone. You’re out there to get a win. However the heck I got to get a win, I’m going to go get it.”

For Hammon, such competitiveness was a learned trait passed down by veterans such as Weatherspoon. It came hand in hand with a shared sense of gratitude instilled by Weatherspoon and fellow veterans such as Kym Hampton and Sue Wicks.

Now, 21 years later — regardless of competition or outcome — both coaches carry that gratitude through their daily life.

“They just loved this moment so much because they’d never had it,” Hammon said. “Whether that’s at the beginning of the league or in Year 27, be thankful for the opportunities. There’s a lot of women that fought really hard to have these moments.”