In 1924, a 20-year-old Chicagoan fibbed his way into the Olympics and won three gold medals at the swimming competition in Paris.

Johnny Weissmuller said he was born in America but word got out that he had actually been born in Austria-Hungary. The New York Times reported that Illinois congressman Henry Rathbone was investigating Weissmuller’s eligibility for the U.S. Olympic Team.

The Tribune quickly came to the hometown hero’s defense.

“Can’t Bar Weiss from Olympics Was Born Here,” an April 14, 1924, Tribune headline triumphantly declared in its follow-up story.

“Johnny said he was born in Chicago, will be twenty years old next June, and has no intention of ever being anything but an American citizen,” the accompanying story reported.

The reality was that Weissmuller was indeed born in Europe while his younger brother Peter was born in America. The brothers swapped biographies when Johnny needed a passport to get to the Olympics. He became the one born after the family immigrated to America.

“Presented with my father’s falsified records, Olympic and government officials were finally satisfied as to his bona fides,” Johnny Weissmuller Jr. wrote in “Tarzan, My Father.” “Thoughts about the scam he and his mother had perpetuated haunted him his entire life. He was worried that they would take away his medals.”

His accomplishments couldn’t be challenged.

“Johnny Weissmuller, the Illinois Athletic Club star, was the sensation of the day, “ the Tribune reported from France on July 21, 1924. “He smashed the Olympic record when he won the 100 meter free style event in :59 seconds, and helped to set a new world mark when he, Breyer, O’Connor, and Glancy, the American relay team, finished well out ahead in the 800 meter relay in :53 2.5.”

The path to those gold medals started at the Fullerton Avenue Beach. When he was 8, his mother, put water wings on him and nudged him into the water.

“I can’t quite explain it except to say it was like coming home,” he told his son. “Swimming? Hell, for me it was easier to learn than walking.”

He lived with his mother, father, brother, and grandmother at 1921 N. Cleveland Ave. When Weissmuller was in the eighth grade, his father deserted the family. Bill Bachrach, swimming coach at the Illinois Athletic Club, would become a father figure to the fledgling star.

Weissmuller had moved on from Lake Michigan to a YMCA swimming pool. But he dropped out of school to help support his mother, a cook at Turnverein, a German athletics and cultural center.

Hoping to break that cycle, he tagged along when a buddy was invited to try out for the swim team of the tony Illinois Athletic Club. His form was not impressive, but his times were.

Weissmuller “held his head so out of the water and kicked and splashed so that it reminded me of a dog swimming,” Bachrach said. “But I held a stopwatch on him and a stopwatch doesn’t lie.”

When Weissmuller finished a run in just over record time, Bachrach handed him an Illinois Athletic Club member’s card. Instead of changing his swimming method, he refined it.

As described in the book by Weissmuller’s son, swimmers generally take a breath by moving their head from side to side, or up and down. Either way creates a drag, like the hull of a speedboat plowing through the water. Weissmuller’s method mimicked a hydrofoil skimming atop the water,

With Bachrach’s refinements, it became Weissmuller’s signature “six-beat-double-Trudgen crawl stroke.”

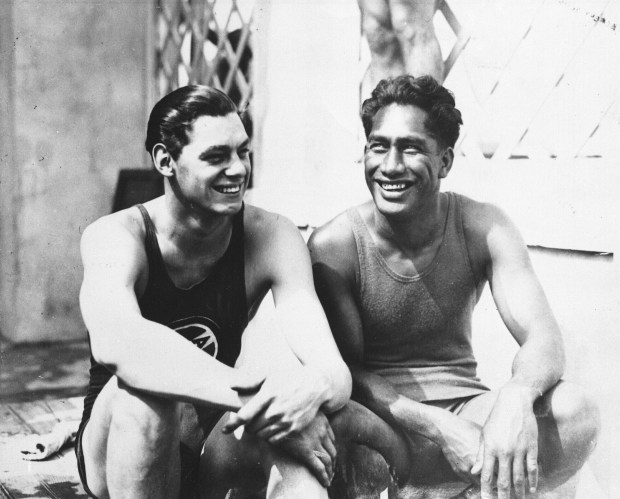

In 1922, Bachrach’s protege broke a world’s record held by Duke Kahanamoku, a celebrated Hawaiian swimmer. After his performance in the 1924 Olympics, preview stories on Weissmuller’s races took winning for granted. One such story awaited the final report with only one question: Did he set a world record?

His Olympic medals made the rich and famous eager to be photographed alongside Weissmuller.

In Hollywood, he had lunch with Douglas Fairbanks and Sol Lesser, a producer pitching him on a movie version of a popular novel, “Tarzan the Ape Man.” Fairbanks, the crown jewel of Tinseltown, wasn’t interested in playing a half-naked jungle dweller and telling his equally white co-star: “Me Tarzan. You Jane.”

“How about this lad?” Fairbanks said pointing to Weissmuller.

“Afraid not,” Lesser replied. “What we need for this role is a star.”

After Weissmuller’s second Olympics in 1928, Lesser would have to stand in line to make him an offer. Weissmuller had become a superstar. He won two more gold medals at Amsterdam in 1928. New York gave him a ticker-tape parade, and MGM offered him the title role in the Tarzan movie that Fairbanks had rejected.

It prolonged his celebrity after he stopped racing the following year. The movie’s success was echoed by about a dozen more. Playing an ape man of action and few words, Weissmuller was known worldwide.

He was playing golf in Cuba when Fidel Castro took over the the island nation. Questioned by Castro’s guerillas he said: “Me Tarzan.” That did not work, so he beat his chest and gave the Tarzan yell: “Oo-uh-hoo-uh-woo.”

Laughing, they escorted him to his hotel.

“These peasants might not have recognized the pope, but they sure as hell knew who Tarzan was,” his son later wrote.

MGM pinned a price tag to his fame on its initial contract: He had to divorce his wife. The studio intended to sell tickets by presenting Weissmuller as the man of a woman’s dreams: handsome, sexy and available.

For reluctantly agreeing, his wife, Bobbe Arnst, got $10,000 to restart her career as a nightclub singer. Weissmuller got $250 a week to start and raises that brought his salary to $2,000 a week—plus a radically changed lifestyle.

Athletic success requires discipline and delayed gratification. Hollywood bred dissipation. Weissmuller and Arnst’s four successors as his wife lived in homes as big as airplane hangars. Weissmuller hung out and drank with movie star friends, competing with Humphrey Bogart in sailboat races to Catalina Island.

Their daily routine centered around drinking. When Beryl Scott, (wife number 3), was pregnant with Johnny Weissmuller Jr., San Francisco columnist Herb Caen: “wrote something to the effect that the kid would probably be born on a cocktail table.”

Weissmuller’s box-office receipts were collected and automatically distributed to vendors, ex-wives due alimony and three children. Eventually his business manager told his client he was broke.

Friends got him hired as a celebrity greeter at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. Standing on a chair he fell, and a series of strokes followed. His son got him into the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital. Maria Gertrude Baumann, his fifth wife, moved him to Acapulco, Mexico, and sold his story to sensationalist magazines that photographed him lying on a shabby cot. She posed as a wealthy German countess. But she lived off the residuals of her marriages.

When he died Jan. 20,1984, Baumann turned his funeral into a circus parade: A dwarf led a defecating chimpanzee. Loudspeakers repeatedly blared the Tarzan yells.

She always said she buried him alongside the ocean in a magnificent cemetery. Finally, his children went to the cemetery and found the man who dug the grave. He said the tomb had yet to be built. The site was covered with brambles and weeds.

“What stands out, at least in my mind, is the fact that for a man of such importance there were fewer than thirty people in attendance,” the cemetery caretaker said. “I was personally embarrassed that such a man would be buried in a plot of dirt and mud.”

Spotting a rose, the caretaker was asked who brought it.

“I have no way of knowing so many people come here to visit the tomb of this fine man,” he said. “I think they loved him very much.”

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com