NEW YORK — Just about everyone over the age of 5 knows what it means to sit in a theater and watch a movie. Many of us have seen a silent film — Chaplin, maybe, exhibited theatrically with a musical score on the soundtrack.

Some of us — in Chicago, happily, it’s pretty common — have heard a keyboard accompanist or a small-group ensemble, or even an entire orchestra, performing with a silent short or feature.

Then there is the benshi experience, which new to me. And now I have located the shadowy intersection of cinema and theater where a kind of delicate magic happens. And I’m grateful I traveled to the Brooklyn Academy of Music last weekend for the first of four U.S. tour stops of “The Art of the Benshi.”

Direct from Japan, following its New York and Washington, D.C., engagements, the eight-person ensemble comprising the “Art of the Benshi” company arrives in Chicago for programs April 16-17 at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Both nights are sold out. A few lucky folks will likely squeeze in, via the rush ticket line.

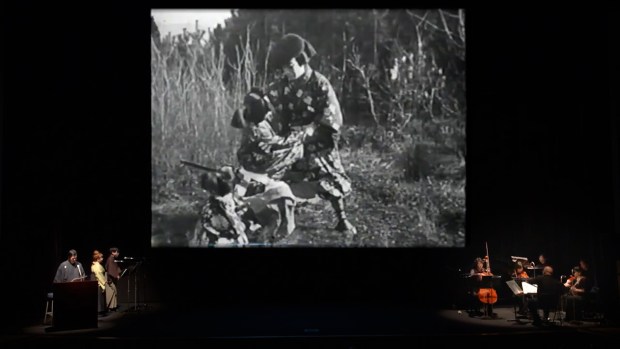

Benshi works like this. On the screen, you’re witnessing a long-lost fragment of century-old silent footage of a samurai in action. Or perhaps the 1918 comedy “Sanji Goto” starring Iwajirō Nakajima (aka “the Japanese Charlie Chaplin”) as a bank janitor who inherits a family fortune. Or, depending on which “Art of the Benshi” program you attend, a silent relic from one of the 20th century masters, Kenji Mizoguchi or Yasujirū Ozu.

To the right of the screen, a four-person orchestra accompanies the action, subtly, drawing out unexpected emotional dimensions not through bombast, but through poetic restraint.

A fifth musician, playing an array of percussion instruments, pins down the left side of the stage. This is where the orator, the benshi, works as well. He or she is actor, interpreter, commentator, sometimes a cultural critic, always the audience’s first responder adding a human voice of many functions.

The benshi tradition, which traveled far beyond the island of Japan, found its footing in 1896, when Thomas Edison’s Kinetoscope made its Japanese premiere. According to benshi scholar and essayist Miyao Daisuke, whose work appears in the “Art of the Benshi” tour’s commemorative book “The World of the Benshi,” the Kobe gun shop owner who exhibited early silents on Edison’s machine first saw it in 1893 in Chicago at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Back home, ready to wow his audience, the man from Kobe decided a few opening remarks were needed, just to set the scene. Later, in Tokyo, he hired a professional gidayū-gatari — a “ballad-drama chanter” — to introduce and explain what audiences were about to witness. By the time the rival Lumière Cinematographe movie equipment was unveiled in Osaka, a year later, the benshi tradition of silent film narrators had begun.

“Benshi” translates roughly to “orator,” deriving from katsudō benshi or “movie talker.” In the silent film era in Japan, which lasted well into the 1930s due largely to the popularity of the benshi, the live performance element felt perfectly at home with this newfangled mechanical medium. Japanese audiences were well used to centuries-old oral storytelling and theatrical forms showcasing a reciter as part of, yet separate from, the world of the story.

At the peak of the benshi’s silent film prominence, some 7,000 of them plied their trade in Japan. The best-known were rock star-level famous, as big or bigger than the stars of the movies they served.

Serve how, exactly? Well, that varied and varies still. Benshi typically write their own scripts. They provide the voices for various characters on screen, speaking aloud the on-screen title cards as needed. But there’s more to it. In Japan a century or more ago, when showing a U.S.-made silent film, a benshi’s script often included some tidbits and observations about the exotic foreign culture depicted (or lampooned) on screen. With a comedy, the benshi might also incorporate something akin to “Mystery Science Theater 3000” wisecracks, freely anachronistic, but in the spirit of the story at hand.

“Think of the film as the conductor, with everybody else on stage the musicians, looking up at the screen. The movie essentially is conducting us, and we’re responding to it.” That’s how master benshi Ichirō Kataoka describes this nearly lost art. We spoke prior to the April 7 BAM rehearsal, along with other members of the tour. The tour’s executive producer Michael Emmerich served as our translator; at UCLA, where he teaches in the department of Asian Languages & Cultures, Emmerich produced some benshi silent film programming in 2017 and 2019, which led to the current four-city U.S. tour.

In their heyday, the benshi worked solo, though other traditions flourished, with two or three benshi dividing up the chores. Chicago audiences will get a taste of both solo and team work. Kumiko Ōmori, the female benshi collaborating with lead benshi Kataoka and fellow performer Hideyuki Yamashiro, has worked extensively in radio and TV in Japan, and on this U.S. tour, she’s proving herself as a vocal quick-change artist of the front rank. In long-lost silent comedy “Our Pet” (1924), which Kataoka discovered at an auction (cost: about $500), Diana Serra Cary stars as the popular silent series character Baby Peggy in a proto-“Home Alone” lark about a foiled burglary and one rather unsettling pre-teen girl’s juggling of various “boyfriends,” also preteens.

“Once you write the script and start performing it,” Ōmori told me, “there’ll be times — especially when you have a lot of characters on screen at the same time — when you have to communicate exactly who is speaking, and when. So you create different character’s voices at different levels. You can’t confuse the audience.”

The live orchestra conducted by Jōichi Yuasa (who also plays the stringed shamisen and guitar) perform both existing and original compositions, the century-old material derived from archival sheet music and notes. At BAM, as will be the case at the Siskel Film enter, the music favored a hushed, spare instrumentation, often strikingly selective in terms of how much silence can be used effectively, and how a single instrument, adding the smallest number of notes, can work on the audience’s own heartstrings.

“We leave space for things,” Yuasa told me. “Particularly with Japanese instruments, the idea of filling up all the available (playing) time with sound is antithetical to our cultural background.”

Put all the visual and aural ingredients together, and you have “The Art of the Benshi,” which isn’t an exercise in “original practices,” really. That phrase suggests something stuffy, or hidebound. Walking out of the Saturday night program in Brooklyn, I felt nothing but gratitude, having been pulled further into some obscure and more familiar silent films than I had before. “It transforms how you experience silent film,” Emmerich told me. “Benshi traveled far beyond Japan, and they worked up and down the American West Coast for a time. It’s an important part of world cinema culture but also U.S. film culture.”

The next’s day BAM program included a solo benshi turn from Yamashiro, who from the stage told the sold-out audience: “The scripts are written by the benshi themselves. So, if the benshi changes, your impression of the movie will also change.” On their own or together, these practitioners of a virtually lost art create a communal spirit far beyond the base-level communal spirit of moviegoing. That too will fade. But today we have it, if we want it. And “The Art of the Benshi” has changed my impressions of what it means to watch and listen to a movie.

“The Art of the Benshi” runs 6 p.m. April 16-17 (sold out); doors open 5 p.m. for rush tickets at the Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State St.; siskelfilmcenter.org

Michael Phillips is a Tribune critic.