What is it about the Midwest that breeds so many serial killers?

What is in the soil that grows the sort of grisly murderers who launch a million headlines? Adam Rapp has wondered for a long time. He was born in Chicago and raised in Joliet in the 1970s, when Joliet was not the best place to grow up. Gangs proliferated. There were rumors of white vans whose drivers offered neighborhood boys a peek at a Playboy. You couldn’t escape to Chicago — killer clown John Wayne Gacy and nurse killer Richard Speck came out of there. Rapp’s father lived in Wilmette, but then John Carpenter’s “Halloween” came out when he was 10 and was based in Haddonfield, a fictional Illinois town “that looked like Wilmette, oak trees, porch swings. And that drove home the immediacy of my worries — I mean, how was I going to use my keys to get into my house and escape from a killer if my hands were shaking that bad?”

Rapp was closer to his fears than he knew.

When he was 5, his family was leaving the Kankakee area when “a driver pulled up next to us on I-57 brandishing a rifle, traveling in the oncoming lane.” Rapp was asleep beside his sister, who locked eyes with the gunman. Their mother, sitting in the passenger’s seat, looked over and clutched their baby brother (Anthony Rapp, who later became an acclaimed theater actor).

The gunman drove on.

That night, the mystery driver, a Chicagoan named Henry Brisbon, later dubbed the “I-57 killer,” killed three people. He was sent to Stateville Correctional, where Rapp’s mother worked as a nurse. (She would also serve as a material witness in Brisbon’s trial.) Stateville, a stone’s throw from their apartment, was home to Speck; Rapp’s mother was friends with the nurses that Speck killed. Stateville also briefly housed Gacy, and near the end of her career, Rapp’s mother attended to Gacy on the day of his execution.

Adam Rapp went on to become a Pulitzer Prize-nominated playwright and author whose themes tend to spring out of legacies of stray violence and social alienation. His new adaptation of S.E. Hinton’s “The Outsiders” — arguably the greatest young adult novel to address those topics — recently opened in previews on Broadway. But also nested in that career has been a question that Rapp hasn’t been able to shake since he was a child:

Why do so many famous murderers come out of the Midwest?

This story offers no answers. How could it? Murder is not a Midwest invention. But why then does the Midwest — and the Chicago area, in particular — appear to nurture such a grim, sensational history of unimaginable killings? Rapp can’t say. But lots of writers have tried. This spring alone, a pair of new novels chew over the question: There’s Rapp’s family epic, “Wolf at the Table,” and Cynthia Pelayo’s “Forgotten Sisters,” which tackles the persistent real-life rumor that a serial killer is targeting young men and dumping their bodies in the Chicago River. Spoiler: As compelling as both of these books read, neither get any closer to an understanding. Next month is the 100th anniversary of the killing of 14-year-old Bobby Franks by two University of Chicago students named Leopold and Loeb. At least morally, we are no closer to understanding that, either. Statistically, historically, New York and California generate more killers than the Midwest, but neither of those places wear them quite like the wheat fields and anonymous apartment complexes of the Midwest.

One reason, perhaps: Free-floating menace doesn’t slip into densely-populated areas as cleanly, or lazily, as it does in literature about the Midwest. I’ve been reading a lot of recent novels and histories about famous (and fictional) Midwest murders and often the covers match the barrenness of the land to a moral barrenness: Bleak horizons and cobalt skies, windmills watching in silence, rusting pitchforks, crumbling wells, dirt-cellar floors and miles of unmarked graves. Our ominous middle of the nowhere seems to be everywhere from Ohio to Nebraska.

As a native of the East Coast (the seat of publishing), I confess to plenty of regional biases: The terrific first line of Chicago novelist Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” — “When I think of my wife, I always think of her head” — lands differently knowing it takes place in Missouri. I don’t think I’m being mean. Lori Rader-Day, another Chicago novelist with knack for Midwest murder, explained: “Cornfields are creepy, man. The Midwest may be written off as a harmless nowhere, where community is everything, everyone cares for each other. But people do feel isolated. I think it’s one reason people turn towards evil.”

As she once wrote: There’s so much potential for darkness in the Midwest.

And that’s not even including Chicago, the nation’s haunted house. Pelayo was born in Puerto Rico and raised in the Northwest Side neighborhood of Hermosa, and still writes her books from there. She said whenever she tours for a new novel, she inevitably meets audiences that assume she pens her horror-tinged thrillers “from a bombed-out hellhole, so I tell them: I’m not scared of Chicago, I love it, I raised children here, I do dumb stuff at night.

“And yet, of course — we have this history of murder that’s hard to really understand.”

Her novels regard Chicago’s past and present as uneasy neighbors, sometimes fantastically, usually violently. We’re reminded in “Forgotten Sisters” of generations of “long-submerged bloated corpses” settled on the floor of the Chicago River. Characters hear echos from the old Union Stockyards — “a great cacophony” of butchering. As in her other books — which address the local history of gun violence and inequality — our contemporary ugliness gets pressed against the city’s paradoxical history with Walt Disney (born here) and “The Wizard of Oz” (written here). Without giving anything away, “Forgotten Sisters” offers a bit of “The Little Mermaid,” meets the real-life S.S. Eastland river disaster of 1915, meets recent whispers (denied by Chicago authorities) of a “Smiley Face” serial killer stalking the city, targeting predominantly young white males.

“We romanticize the death of millionaires on the Titanic,” she said, “and forget the 844 people who died on the Eastland (in the Chicago River) were largely immigrants who helped to build Chicago. And the way we’ve forgotten their loss, that’s a double tragedy.”

So, in her novel, there’s karmic, supernatural revenge for the wrongs of the past.

Pelayo has always wondered, she said, “if there’s something more” to so much horrible spectacle in the Midwest. But then, she brakes just short of supernatural explanations.

Rapp, too.

His mother kept most of her professional connections to famous killers a secret. She rarely discussed her work at Stateville with her children. They knew she had lived in Manteno not far from the state psychiatric hospital, but not until after she died in 1997 and an aunt gave Rapp a shoebox of his mother’s possessions did he piece together her broader history with mental illness: “That started my weird fascination with this simple woman’s frequent proximity to extraordinary acts of male violence.” But of course, there’s nothing supernatural to that. His book, “Wolf at the Table,” is fiction: It tells the story of a family marked by mental illness. A father abandons his North Shore life after a voice tells him to kill. A brother spends years wandering, and killing, largely unrecognized. There’s also a main character who reads an awful lot like Rapp’s mother.

She’s a nurse who works with Gacy, and also knew Gloria Davy, one of the (real-life) nurses killed by Speck in 1966 on the Far South Side. The morning she learns Davy was murdered, Rapp’s character still puts on her nurses uniform and reports to work. “As her train clatters past Wrigley Field,” Rapp writes, she gets hyper-aware of her uniform, and this latest Chicago tragedy: “Do they think she’s playing some cruel joke?”

In the second season of the Hulu series “Fargo,” an unseen narrator (voiced by Martin Freeman) reads from a volume titled “The Big Book of True Crime in the Midwest.” It’s a fictional book conceived by series creator Noah Hawley (a New Yorker), and like many histories of Midwest murder, it looks light on Native American massacres and white supremacy. But it also appears ancient and dusty, and therefore, irrefutable.

After all, the image of Midwest as a cauldron of violence was shaped through writing, and predates the days of Al Capone. Journalists recycled the idea that the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was divine retribution for a place so corrupt. As early as 1899, Henry Blake Fuller, among Chicago’s first full-time novelists, gave a talk at the Fine Arts Building in which he described the city as “a hideously makeshift horror.” He wasn’t even referring to H.H. Mudgett, executed three years earlier, and now considered among the United States‘ first serial killers. From his Englewood drugstore, Mudgett (better known as H.H. Holmes) preyed on visitors to the World’s Columbia Exposition; more than century later, he’s known as the subject of the best-selling “Devil in the White City.” Yet not long after the fair closed in 1893, there were already best-selling accounts — written by Chicago police officers — of crime at the event.

By the time Theodore Dreiser published “An American Tragedy” (1925) and Richard Wright wrote his own American tragedy “Native Son” (1940) — both centered on accidental, yet seemingly inevitable killings — the image of a fetid metropolis encircled by dark fields of scarecrows was indelible. It became less shocking to hear of a William Heirens, the Lipstick Killer of Lincolnwood, who wrote in lipstick at the scene of a 1946 murder: “Catch me before I kill more. I can not control myself.” Yet, as Sarah Weinman, among our finest contemporary crime writers, told me: “It’s important not to think of these things as happening because of something in the local water. There’s nothing in the water. People link horrible events, though the only thing connecting killers like this is the often-marginalized communities they prey on. And that’s not a Midwestern thing.”

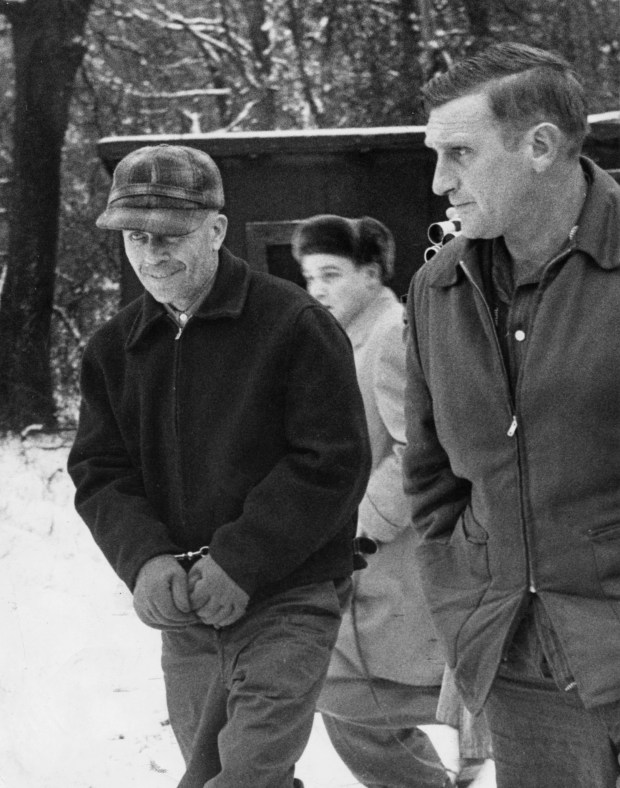

Still, when Harry MacLean was growing up in Nebraska, if you wanted to know where the violent people were, he said, you looked east to Chicago. “Then Charlie Starkweather came along in 1958 and transformed our perception of ourselves,” MacLean said. As he wrote in last winter’s “Starkweather: The Untold Story of the Killing Spree that Changed America,” the landscape may be cold and lonely, populated by cows “huddled” against haystacks on bland afternoons, but if you “played by the rules,” took care of your family, remained decent and went to church, then “life will be good.”

It was a white Protestant worldview, and Starkweather, at 19, upset its math. He drove through Lincoln towards Wyoming with his 14-year-old girlfriend, Caril Ann Fugate, killing indiscriminately. He killed in homes, fields and on highways. He had no history of behavioral issues. He had a stable home. “But I remember true fear on adult faces,” MacLean told me. “There was a sense Charlie Starkweather could be hiding in your barn, or step into your living room. I heard stories of people hiding out as far as Iowa. A sense of terror, across a region, was new.” Starkweather eventually killed 10 people.

A year later, four members of the Clutter family were murdered in Kanas, also seemingly at random, a crime immortalized by Truman Capote in his classic “In Cold Blood,” which painted a portrait of endless fields of wheat so isolating it was mainly called “out there.”

The land itself, see, was lethal.

As far back as the 19th century, when the homicidal Bender family trapped, robbed and murdered wayward travelers who happened to be passing by their home on the southwest Kansas plains — recounted by Susan Jonusas’s history, “Hell’s Half-Acre: The Untold Story of the Benders, a Serial Killer Family on the American Frontier” (2022) — visitors wrote home that the buildings here wanted to sink into the dirt. When husbands vanished en route to Illinois, wives were told that it was as if the prairie swallowed them.

Rapp, who is also writing an upcoming TV series about the Wisconsin serial killer Ed Gein, “can find the bleakness of this region at times especially isolating, opening brooding thoughts for certain men in need of vitamin D.” Gein’s crimes inspired the Maywood native Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel “Psycho,” subsequently inspiring the Alfred Hitchcock film, and decades later, the Buffalo Bill killer of Thomas Harris’ “Silence of the Lambs.” After Gein’s mother died, he started robbing graves and killing people, partly for taxidermy. He lived alone in a farm house without water, due north of Wisconsin Dells.

Indeed, isolation, physical and mental, plays an outsize role in these tales.

“Slenderman: Online Obsession, Mental Illness and the Violent Crime of Two Midwestern Girls,” Kathleen Hale’s 2022 account of a stabbing death outside Milwaukee, is driven by boredom, a suburban legend and the 12-year-olds who believe it. Yet, as Bloch wrote about Gein, Wisconsin was “hardly the proper setting for such characters.” The Slenderman killing was not unlike the killing of Bobby Franks by Leopold and Loeb in that both murders came out of intense friendships between seeming innocent kids. Leopold and Loeb, college students, came from rich Chicago families. Leopold, wrote crime writer Miriam Allen deFord decades later, was taught as a young child that his family’s “great wealth gave him special privileges and immunities.”

Because of course it does.

But that doesn’t fit the archetypal Midwest character. Generosity, ordinariness, neighborliness — that’s who we are. It’s also those qualities, however, that led John Wayne Gacy — a party clown and REO Speedwagon fan in good standing with the Junior Chamber of Commerce — to go unsuspected. When women began vanishing around Gein’s farm, he would joke with locals that he was definitely responsible. As if in a parody of Midwest naiveté, Leopold and Loeb went to a hardware store on 43rd Street and bought a single rope, one chisel and a vat of hydrochloric acid, no questions asked.

Is this why the Midwest has so many notorious crimes?

Because Midwesterners are too nice? It’s as good an answer as any. But doubtful. Rapp believes: “This is an American narrative, a dream of a home, a garage, a car, four kids, and what comes with it are killing sprees. And we don’t know why, not really.” Evanston writer Nina Barrett, author of a 2018 history “The Leopold & Loeb Files,” said the relative newness of the University of Chicago in 1924 led some Chicagoans to ask if liberals art educations were breeding immorality. In Nebraska, after Starkweather’s capture, locals blamed the radicalness of Elvis, James Dean, greasers and the sudden popularity of rock music. Today, MacLean said, people still visit the open pastures where the killings occurred, as though some new clue might reveal itself in the soil.

But if I had to bet, Bruce Springsteen has come the closest to the truth.

His bone-dry 1982 acoustic masterwork “Nebraska” was written about Starkweather, and narrated by the killer. At the song’s end, Charlie is asked why he did it, and his reply is plaintive, honest and chilling: “Well, sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com