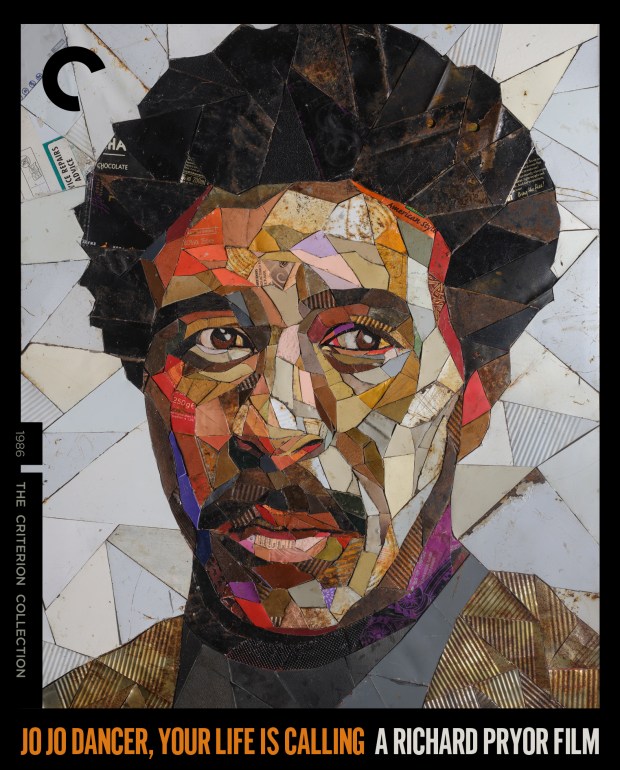

There are a lot of landmark anniversaries this year. “Jaws” turns 50. As does Springsteen’s “Born to Run.” “Saturday Night Live” will formally mark a half-century next month. The New Yorker will reach 100. Yet here’s an anniversary fewer will mark and no one will celebrate: Soon, we will have been without Richard Pryor for two decades. He died in 2005, and as the New Yorker’s Hilton Als writes in the liner notes for the Criterion Collection’s new edition of “Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life is Calling,” if you grew up listening to Pryor, you have a hard time not hearing that voice. The confusion, the self-consciousness, the fearlessness. You still hear it.

Yet, watching the forgotten “Jo Jo Dancer” again — Pryor’s only feature film as a director but a box office disappointment when it debuted in 1986 — is also to be reminded we came close to losing Pryor 45 years ago.

You might even say we did lose him back then.

In the late 1970s, at the peak of his fame, the Peoria-born Pryor was visiting family in Illinois when he stopped breathing and was rushed to a hospital. He’d had a heart attack, which he later characterized in his 1979 stand-up classic, “Live in Concert,” as a stroll in the yard interrupted suddenly by his heart demanding, “Don’t breathe.” Pryor, playing his heart, punches himself for breathing, then kicks himself as he turns to God: “You think about dying, ain’t you? You weren’t thinking about that when you were eating all that pork.”

That bit echoes through “Jo Jo Dancer,” which starts with an even scarier real-life episode no one expected Pryor to recover from. Pryor calls himself Jo Jo Dancer in the movie and relocates the story to Ohio (despite filming in Peoria), but by 1986, the contours of his history were well known. Being raised in his grandmother’s brothel in Peoria. Imitating Bill Cosby until he discovered his own radical voice. Becoming a massive superstar who squandered his once-in-a-generation talent on drugs, Hollywood and womanizing. The movie begins with Jo Jo, a famous stand-up, in a hospital bed, wrapped in gauze, near death, unrecognizable after setting himself on fire while freebasing cocaine. The ghost of Dancer climbs off the gurney and chastises his own scorched body — Now, what did you do this time, Jo Jo?

It’s a queasily personal reckoning for a superstar who, in the ‘80s, was one of the most famous people in the world. Indeed, we see Pryor (playing Jo Jo, though really, himself) on his knees, scouring a shag rug for any coke residue, desperately addicted. Then he douses himself in rum and sets himself on fire. The actual incident in Los Angeles was much uglier. Pryor, on fire, raced out onto the sidewalk in front of his home, screaming “Haven’t I brought happiness to anyone in this world?” The movie leaves out that part, for the better. But if you were alive in 1980 and recall hearing of the incident, you’re reminded of an overwhelming sense of wasted talent.

Chicago journalist Abe Peck (later a longtime journalism professor at Northwestern University) reacted in the Chicago Sun-Times with the same raw, helpless confusion many of us felt at the time: “All I know is that I very badly want Richard Pryor to live.”

Pryor recovered, of course, only to learn soon after he had multiple sclerosis. By the time he died decades later, it was noted often that one of the harshest truths of American life was that Pryor and Muhammad Ali, two of the most famously verbal Black geniuses, were nearly mute. Pryor, though, largely lost his bite after his self-immolation, which the film (and later Pryor’s family) characterized as a suicide attempt. “Jo Jo Dancer” plays now like a stab at reviving him as a serious actor, so memorable in Paul Schrader’s “Blue Collar” and the Billie Holiday biopic “Lady Sings the Blues.” The problem was Pryor became a star after those roles, and when the fire slowed him down, he retreated into toothless, ill-suited, well-paying roles, starring in a series of terrible but popular comedies — “Bustin’ Loose,” “The Toy,” “Superman III,” “Brewster’s Millions” — that asked nothing more of Pryor than loose-limbed mugging.

As Gene Siskel wrote in the Tribune: The irony of Pryor’s decline was that, since he had built his comedy around uncompromising truth, “if he doesn’t play a character as smart or wicked or wily as we suspect him to be, we simply won’t accept his actions.”

In fact, as flawed as “Jo Jo Dancer” may be — Pryor was not the best director of himself — in hindsight, it has the shape of an artist’s recognition of his missteps, before health or addiction rob him of a chance to explain himself with clear eyes. What’s here, and not, make a compelling case for another, grander epic about Pryor’s story.

Among the extras on the Criterion release is a full episode of “The Dick Cavett Show” from 1985, while “Jo Jo Dancer” was still in post-production. The talk show host, knowing the film was an autobiography, asked Pryor what being raised in a brothel was like. “I guess you could call it a ‘brothel,’” Pryor replied, “but we called it a whorehouse.”

Pryor was that blunt about the Midwest and his history, though the wider context is even more fascinating: His grandmother, Marie, who was first married at 14, arrived in Peoria via Decatur and quickly became a rallying point for local sex workers. In his terrifically researched 2014 biography, “Becoming Richard Pryor,” Scott Saul explains how, despite the city being used in a famous question of taste and temperament (“Will it play in Peoria?”), in the first half of the 20th century, Peoria was Sin City. The illegal business of gangsters and gambling and prostitution sat comfortably alongside official Peoria; for a time, vice flourished so widely that Pryor’s family ran both a series of brothels and legitimate licensed nightclubs.

There is so much material here you wish Pryor had been even more ambitious with “Jo Jo Dancer.” He paints the red-light district of Peoria with a 19th century sitting-room opulence. He stages a violent run-in between Jo Jo and his abusive father as if he were Elia Kazan making the soundstage shake. Pryor suggests so clearly that he thought of himself as navigating a series of stages, you wish that the comedian — who was labeled “emotionally unstable” early on and shuttled through seven schools in Peoria over 10 years — had included his fifth-grade year. As Saul writes, Pryor found himself embraced by a teacher who considered the child uncommonly insightful and so, in exchange for being on time, she would let him perform 10 minutes of jokes for the class every Friday.

As Pryor often said, the larger-than-life (and lower-than-life) characters who came through his family’s businesses supplied a lifetime of material. That life would become his routine. He told Cavett about how, as a child at the movies, he waited for actors to exit the screen and then raced behind the theater curtain, expecting to meet the cast. It’s a telling anecdote from a guy who eventually committed his body so completely to art.

That wide-eyed innocence fills the Midwest scenes in “Jo Jo Dancer” with an authenticity that pays off later when Jo Jo, faced with an audience rebelling against his four-letter words, decides to ditch his congeniality for a countercultural edge. Again, the story, however muddy and apocryphal as it likely was, tends to the spectacular. As Pryor once explained his stylistic change of heart: He was playing Las Vegas, he looked out, he saw Dean Martin and he had a nervous breakdown, but also, a revelation: He would never become Bill Cosby. There already was a Bill Cosby. He asked the audience “What the (expletive) am I doing here?” and, in their silence, walked off.

As a cultural earthquake, Pryor’s decision to get political and unedited was as game-changing as Bob Dylan going electric. Pryor revolutionized how frank an artist could be on race and sex. Someday there’ll be a biopic that leans into that stage myth with as much tension as “A Complete Unknown” does with Dylan smashing expectations at the Newport Folk Festival. The scene will probably be inspiring and riveting — Oscar ready.

In “Jo Jo Dancer,” though, Pryor shows himself as his usual stunned self. He stammers. He flails. He fights back though mostly, he looked bewildered by himself. Then later, he channeled it into something new. Als explains the feelings this lost movie stirs up as well as anyone: “It makes me miss all that Pryor was not able to do in this life because of his life, but also entirely grateful for what he was able to leave behind.”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com