Charnae Harmon was just 11 years old when her family moved into the Henry Horner Homes in 1985.

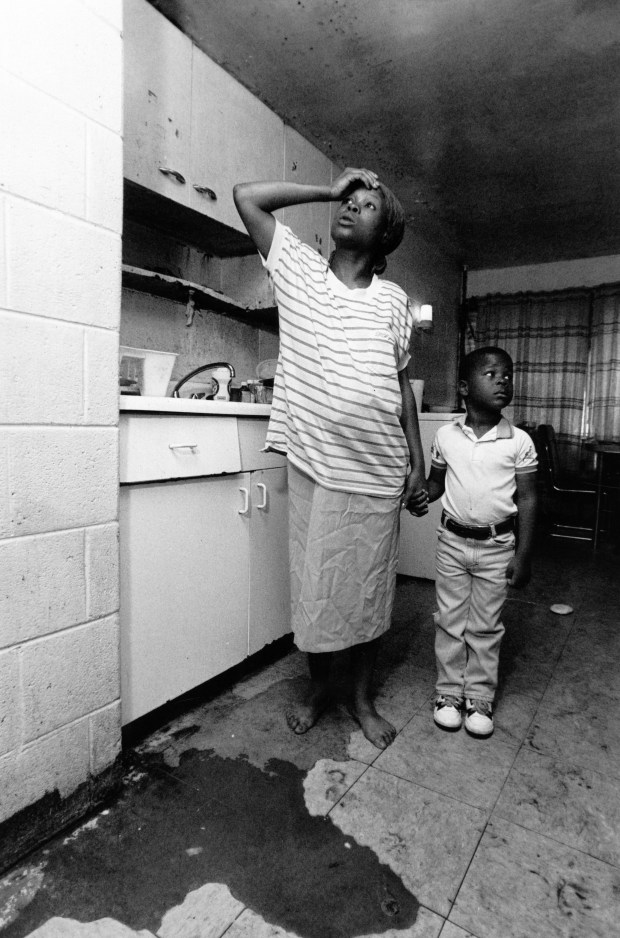

Harmon recalls the “horrible conditions” that characterized her childhood inside the Horner high-rises: infestations, violence and perpetually unresolved maintenance issues.

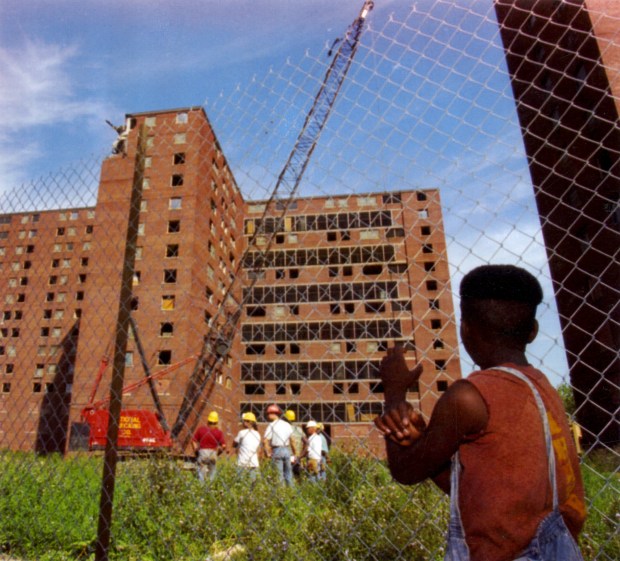

Ten years after Harmon moved in, the first wrecking ball struck the walls of the infamous public housing complex on the Near West Side. The demolition of the Horner towers was praised as major progress at the Chicago 1996 Democratic National Convention as former Horner residents anticipated the rebuilding of new and well-maintained town houses on the site.

Now almost 30 years later, the last step of the Horner redevelopment is about to be completed as the DNC returns next week to the United Center, which sits beside the former public housing high-rises. The Chicago Housing Authority has moved to end a legal agreement that has bound them to the former Horner residents since 1995, arguing that their part of the job is done.

Yet many in the Horner community say that CHA is still failing to hold up its end of the bargain, claiming that their homes have again fallen victim to neglect and disrepair.

“Once it was decided to tear down the high-rise buildings and start building town homes, everything was good,” Harmon said. “We all moved into our new town homes, everything was great moving in. But as the years progressed … the maintaining of the property started to go down.”

The “Horner model” — epitomized through the site’s low-rise, mixed-income town houses — was an initial test case for the reimagination of public housing, according to D. Bradford Hunt, chair of Loyola University Chicago’s history department and a Chicago public housing scholar. The architects of the Horner deal hoped that their work would act as a shining example for other progressive redevelopment projects in Chicago and the greater United States, he said.

As the CHA launched its “Plan for Transformation” in 1999, many other public housing developments across Chicago faced a similar fate as the Horner high-rises. Troubled projects such as Cabrini-Green Homes, ABLA Homes and Robert Taylor Homes were slated for demolition, leading to relocation of their residents.

The Horner consent decree was “one of the better deals” to emerge in that period in terms of protecting residents, Hunt said.

“(Horner’s redevelopment was) catalyzed in part because of the 1996 Democratic National Convention, no doubt about it, so there is an interesting parallel moment,” Hunt said. “It’s interesting to revisit 28 years later. We were here once before. What about those public housing residents? What was it then? What is it now?”

As president of the local advisory council, Harmon, now 49, advocates for former Horner tenants facing housing conditions issues in both the redeveloped neighborhood and scattered-site public housing around the city.

In 2018, Harmon and her son were forced to relocate from the Horner neighborhood to a CHA unit in East Garfield Park, she said. She was told that the displacement would only last a year, until renovations of her unit were completed.

More than six years later, she’s still living in her “temporary” housing. Harmon said she worries about gang violence, especially after a shooting a few years ago in the gangway of her apartment building.

“I feel like we’re still dealing with the same battle from the very beginning,” Harmon said. “There’s a lot of progress that still needs to be made. We’re still dealing with repairs that needed to be made for years, from the very beginning. The floor repairs, the water leaks, plumbing issues, we’re still dealing with that today.”

The 1995 amended consent decree obligated CHA to rebuild a specific number of public housing units to compensate for those lost in the demolition of the Horner high-rises. This agreement gave displaced Horner residents a right to return to the rehabilitated units or to relocate to other public housing around Chicago.

Additionally, the decree specified that CHA must keep the new units of former Horner residents in good repair, providing them with “decent, safe and sanitary” housing conditions unlike those which they had faced in the demolished apartments.

With construction underway on the final set of replacement units, CHA submitted a motion in October 2023 to officially end the consent decree after almost three decades of redevelopment.

Yet lawyers for the Horner plaintiffs argue that CHA has not fulfilled a key obligation under the decree, due to their alleged neglect of the newly built or renovated units. Many in the Horner community claim to have spent years warding off severe maintenance issues such as flooding, mold, sewage leaks, rotting floors, malfunctioning heating and infestations.

“Because this lawsuit is in active litigation, CHA cannot comment at this time on specific issues raised in court filings,” housing authority officials wrote in a statement. “However, CHA values our residents, and we take their concerns seriously. We continue to work closely with our third-party property managers to remediate resident issues in a timely manner.”

CHA’s motion to end the consent decree remains pending and is being litigated by the parties, an attorney for the Horner plaintiffs confirmed Tuesday.

“These are people living in poverty who don’t have choices,” said LaTanya Jackson Wilson, vice president of advocacy at the Shriver Center on Poverty Law and member of the plaintiffs’ legal team. “They can’t just pick up and find another place to live. This is public housing. It should be safe, it should be healthy, it should be sanitary, and it is not.”

‘There have been promises’

Dion Salley pushed his brother Davon’s wheelchair across the asphalt as they headed back toward their unit in Westhaven Park, the new name given to the redeveloped Horner neighborhood.

The Salley family moved into their current Wood Street home from Humboldt Park over five years ago after Davon Salley was injured in a shooting.

Having requested a wheelchair-accessible home, the family was placed in a ground floor unit. Yet Dion Salley said that despite years of asking, they have still not received other necessary accommodations, including a wheelchair-accessible shower.

When the family asked permission to remove the carpeting in their unit, which hinders Davon Salley’s movements, Dion Salley said that they were required to provide a doctor’s note.

“We did that, they still haven’t fixed it,” Dion Salley said.

The brothers, both 23, said their stove has been broken for multiple months and their bathroom ceiling is covered in mold. They have put a bucket on the ground to catch water leaking from a hole in the roof of their laundry room, which Dion Salley said has been there since 2021.

“They don’t do nothing. We call them, I don’t know how many times (we’ve) called them, they don’t do nothing,” Dion Salley said. “We tell them to fix it. We pay the rent and everything, because that’s what they tell us. If we don’t pay the rent, we ain’t going to get it fixed.”

The mixed-income Westhaven Park development is primarily made up of town houses, with a few larger apartment buildings, and spans across dozens of acres on the Near West Side north of the United Center. Construction began in the late ’90s with the “Horner Superblock” of all-CHA town houses — which were later renovated again to include affordable and market-rate units — and is still continuing today.

The final phase of the development, an apartment tower on Damen Avenue, is expected to be completed by the end of 2024, according to a CHA spokesperson. Of its 96 units, 38 will be reserved for CHA residents, 25 for other low-income households, and 33 for market-rate customers.

Already, the black and white building towers over the low-rise town homes nearby.

To be sure, several residents interviewed across Westhaven Park, from both CHA and market-rate units, said that they’ve never had a major maintenance issue.

Rita Vanpot, who has lived in the development for 13 years, said that even though it’s a bit “slow,” she has always been able to get her work orders resolved.

Jacob Turcano, 25, has lived in an apartment tower in Westhaven Park for two years, paying market-rate rent. He said he has not experienced any significant maintenance problems.

Almost two-thirds of the units in Turcano’s mixed-income building are reserved for market-rate customers. In other segments of Westhaven Park, homes earmarked for CHA residents can make up 50% or more of the total units.

“We’ve enjoyed it,” Turcano said. “I’d say really the only concerns are occasionally there’s some suspicious activity going on down the street, when multiple police have been called.”

However, other residents spoke of ongoing struggles and neglectful management.

Romal Jenkins, 45, was born into the Henry Horner Homes, where his mother had lived since 1966. After the high-rises were torn down, he said he moved around for a bit before settling back into a unit in Westhaven Park.

In his current home, Jenkins said he’s still facing constant issues with his water and electricity, including leaks. No matter how much he cleans, he said, insect infestations still come back.

“I’ve been over here all my life,” Jenkins said. “They’ve been promising us for years, since the projects (were) up. There have been promises.”

When asked if CHA’s guarantees of better conditions have ever been fulfilled, he shook his head.

The Horner plaintiffs’ response to CHA’s motion to end the consent decree, which they submitted to the court in December 2023, includes written declarations from several residents attesting to pervasive health and safety issues in their homes.

These tenant declarations detail, among other incidents, multiple cases in which residents or their guests stepped through holes in the floor because of unresolved water leaks that caused softening and rotting of the wood.

Eric Sirota, an attorney for the Horner plaintiffs, said that it would be “improper” to terminate the consent decree given CHA’s noncompliance with a central obligation of the initial agreement.

“One of the underlying assumptions of the consent decree is that replacing poorly maintained units with poorly maintained units doesn’t really fix the problem,” Sirota said. “The consent decree ensures that history can’t repeat itself and that the units in the Horner community have to continually be well maintained.”

Frederick Alonzo grew up in the Horner high-rises and now lives in the renovated Horner Annex, the only original structure still standing. While taking his dog on a walk, he said that he wasn’t surprised that certain maintenance issues were ongoing.

“It’s typical, it’s the projects,” he said.

He sees roaches, but the property managers send in an exterminator twice a month, he said. In his experience, maintenance has also been quite responsive.

“This is probably a little better (than the original Horner high-rises), they’ve got more control of the violence,” Alonzo said. “It’s a little bit cleaner. But as far as that, ain’t nothing really changed.”

Decades of litigation and tenant organizing

Litigation between the Henry Horner Mothers Guild and CHA has been ongoing in federal court since 1991, when a group of mothers living in the high-rises banded together to demand safer conditions for their families.

Annette Hunt, an original member of the Mothers Guild, said that her foray into tenant organizing began with the desire to create an after-school program for Horner children, providing them with a safe space amid a wave of robberies by gang members.

Hunt moved into a high-rise in the Henry Horner Homes with her mother and siblings in 1972. She said that when they first arrived, the development was “gorgeous” and well-kept. By a decade later, however, Hunt said that everything “just started to go downhill.”

Hunt and her children had to sleep with cotton stuffed into their ears to stop roaches from crawling into them. The stairwells were always pitch-black, and maintenance requests went unresolved as the building started to “basically fall apart,” Hunt said.

Four years after the Mothers Guild sued CHA, a definitive agreement was reached in the form of the 1995 amended consent decree. The Horner towers began to come down soon after.

“After you’ve been living in slums for so long and now you’re seeing progress, you have that feeling of hope that things are going to change and things are going to get better,” Hunt said. “Filing that court decree was the best thing we could have ever done. … it was just a better quality of life that we were looking for.”

In addition to mandating the rehousing of all displaced residents in safe, well-maintained units, the 1995 decree dictated that a tenant organization known as the Horner Residents Committee would have a say in each step of the redevelopment process.

The decree “helps ensure the resident council’s ability to be in dialogue with and give input to CHA,” allocating funding for the residents to hire a paid external consultant, according to Sirota.

Horner tenant organization leaders allege that the CHA submitted a motion to end the consent decree without giving them any prior warning, which they said blindsided them.

However, CHA claims that they have always openly expressed their intention to conclude the consent decree once construction neared completion, sharing this at meetings “throughout the years” that have included the plaintiffs’ attorneys, resident leaders and other community members.

Their last court-mandated phase of construction is 70% complete, a CHA spokesperson said Aug 9.

“As such, this is the appropriate time to conclude the decree,” wrote CHA in their statement. “CHA leadership recently met directly with residents of Westhaven and will continue to be responsive to their needs.”

Yet even as the development nears completion, some believe that CHA is still far from fulfilling its obligation to the original occupants of the Horner high-rises.

Hunt, who still lives in CHA housing just across the street from the United Center, said that she and her neighbors are now facing many of the same challenges they did in the Henry Horner Homes.

The roaches are back in full force, she said, as well as water leaks. Air conditioning and heating equipment break regularly, as do stoves, refrigerators and even doors, according to Hunt. When maintenance workers come, they often close out the work order even when no repair has been successfully made, she said.

Hunt fears that if the consent decree ends now, CHA will no longer be held accountable to her community. Progress has been made, “but we’ve got a long way to go,” she said.

“I would really like to see this court decree stay in place, as this is something that I have done from my heart for people who don’t have a voice for themselves,” Hunt said. “To come back and see the same thing that’s existing today, and we’re in 2024, is sad, because we was on our way to a better place. How did we go backward? That’s the question.”