In 2022, art historian Jonathan Katz and a team of curators unveiled an ambitious exhibit: a survey of more than 100 artworks created by, or referencing, individuals experiencing same-sex attraction. That exhibition, “The First Homosexuals,” took over one floor of Wrightwood 659, a Tadao Ando-designed exhibit space in Lincoln Park funded and operated by philanthropist Fred Eychaner’s Alphawood Foundation.

But Katz always dreamed bigger.

“It was COVID that put the kibosh on those plans,” he said of the exhibit’s first iteration. “Most museums had, at that time, loan moratoriums.”

Now, “The First Homosexuals” is back at the scale Katz intended. More than 350 artworks have taken over Wrightwood 659, this time over all three of its levels.

Visitors to the 2022 iteration will recognize works by Gerda Wegener, married to transgender artist Lili Elbe, and Konstantin Somov, a gay Russian artist. Others are new to this expansion, like doodles by author Federico García Lorca, a sculpture by actress Sarah Bernhardt, and the only full-length portrait of Oscar Wilde painted in his lifetime.

“The reception in 2022 was just incredible,” said Chirag Badlani, executive director of the Alphawood Foundation. “Essentially, the day we closed, we said, ‘Let’s start planning.’”

Some artworks bring the suppressed queerness of their makers or their subjects to the fore. “The Man in Black” is a 1913 portrait of Art Institute benefactor Robert Henry Allerton by Glyn Philpot, an acclaimed British painter whose work appears throughout “The First Homosexuals.”

Allerton and Philpot were once lovers; the Allerton likeness, with rosy cheeks and arched brows, is a stark contrast to the other Hemingwayish depictions of Allerton circulating at the time, including a full-page Tribune spread hailing him as the “richest bachelor in Chicago.”

Featured sculptors and lifelong partners Frances Loring and Florence Wyle met in Chicago, where both studied at the School of the Art Institute with Lorado Taft.

But “The First Homosexuals” doesn’t lionize its subjects, either. This time, the exhibit makes no bones about the Nazi sympathies of artists like Marsden Hartley and Elisàr von Kupffer, both of whom painted voluptuous, ambiguously gendered young men. It also unflinchingly includes works that betray the artist’s own prejudices, like a pair of disparaging Western artworks depicting two-spirit — or gender variant — Native Americans.

“We go back all the way to the first invasion of the United States and Latin America by the Spanish, when European attitudes about sexuality rewrote Indigenous attitudes,” Katz said.

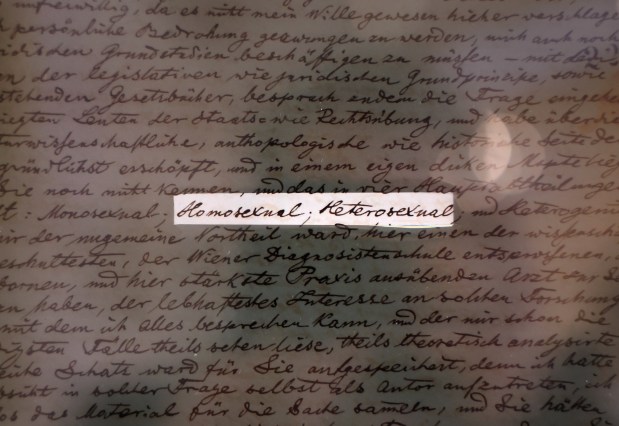

But, as with the 2022 iteration, Katz and his team kept most of this exhibition focused on the span between 1869, the year the word “homosexual” was coined, to 1939, during the rise of fascism in Europe. As the exhibit argues more comprehensively than before, by becoming a discrete identity, homosexuality became the basis for community — finding a common language for difference — but it was also further pathologized. Visitors exit through an archway superimposed with the famous photograph from 1933 of Nazi book burnings in Berlin.

“The book-burning image that everybody knows is the burning of Hirschfeld Institute — it’s that library that’s being burned,” Katz told journalists during a recent walkthrough of the exhibit. “We wanted them to leave through this exit in order to make clear the dangers we face.”

Those dangers — the ascendancy of anti-gay governments worldwide — interfered with this exhibition far more than in its 2022 iteration. Visitors will notice two gray-scale reproductions on display in lieu of the original artworks. The sheets represent works by Slovak and Hungarian painter Ladislav Mednyánszky and Colombian artist Hena Rodríguez, both of which were withdrawn from the exhibition.

The loans of Mednyánszky’s paintings were canceled by the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava at the last minute; 65 museum staff, suspecting state intervention due to “The First Homosexuals” theme, resigned in protest. Meanwhile, the two Rodríguez charcoals were withdrawn by its collector, fearing for the works’ safety in the U.S. after the election of Donald Trump.

“It is an index of our moment that Colombians felt their artwork would not be safe in the United States under Trump,” Katz said.

Even showing “The First Homosexuals” at Wrightwood 659 requires the kind of precautions typically associated with a much larger institution. Upon arrival, visitors must present an ID for entry. Gallery attendants double as security guards.

Though Badlani says there are certainly discussions about touring a smaller version of the exhibition, Katz suspects “The First Homosexuals” now faces a higher glass ceiling in the U.S., particularly among museums large enough and prestigious enough to take it on.

“The director of one of the most important museums in the world said to me, ‘This is exactly the show that I would like to have. And it’s for that reason that I cannot show it,’” Katz said.

“The First Homosexuals,” runs through July 26 at Wrightwood 659, 659 W. Wrightwood Ave; related film series are screened every Wednesday in June; $15 online ticket reservations required, wrightwood659.org.

Hannah Edgar is a freelance writer.