There’s a slyly damning scene in Donna Seaman’s new memoir about her talent/habit/mandate for reading all the time — just reading and reading and reading, nonstop, from her childhood in the Hudson Valley to her longtime career as a Chicago-based critic. In this scene, Seaman is shoplifting. She’s a kid, but not stealing candy. She’s pocketing Dostoevsky. She’s slipped a copy — here’s the funny part — of “The Idiot” into her coat. The store clerk is not oblivious. Seaman is asked if she was planning to pay for that.

She sweats, then blurts earnestly: “Who is the Idiot?”

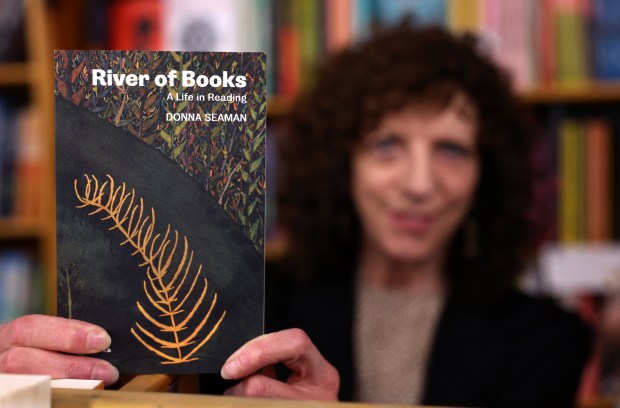

“River of Books: A Life in Reading” is not about a life of crime and misrule. It is not the story of how a former Newberry Library conservator (which Seaman was) goes on the lam for pilfering the work of Russian novelists only to remake herself into an organizing force in Chicago’s literary community (which Seaman has been for years). It’s about the act of reading above all pursuits — for better and worse. She writes about the idea of books as food for thought with such ravishment, that you picture her chewing paperbacks. When she writes of being a child fixated on the word “island,” how it’s made up of different words — you picture a child discovering an island and reading all day and never being bothered.

We met the other day on the Northwest Side, in her neighborhood library branch. She has a long animated face and curly hair and a friendly, generous manner that belies the fact that she would probably rather be home reading a book right now than talking to a reporter.

“Oh, I was such an antisocial kid,” she remembers. “I was a moody kid, I could get uncommunicative. My parents would be like, ‘Please get outside and stop reading and be a child!’ I was aware that my reading was an avoidance tactic. I am still like that. I am super private and I like quiet and I am still most comfortable with a life like that. But I am not a complete introvert. I am interested in people. Ironically, though, that depletes me, and so spending time with people means having to recharge, and that means reading something. As a kid, all I wanted to do was read. My father — a marvelous person, an engineer at IBM — he commissioned me in a way. My allowance would be based on my reading something and then writing a book report about it for him. And I was reading adult books. Dickens and such. Louisa May Alcott. I went for the serious, the classics. I had a crush on David Copperfield. He became like my imaginary playmate. I also had real friends, close friends. No, I was not a psychopath. I was shy and preferred small groups but eventually, I became an all-out partier. I loved going out to bars. I balanced things.”

If you’ve ever run into Seaman out in the Chicago literary world — and it’s hard not to — you might say she has balanced things better than she lets on. She’s been hosting different iterations of the Open Books radio show since 1994. She was a guiding hand in the creation of the American Writers Museum on Michigan Avenue. A month doesn’t go by where Seaman isn’t interviewing an author or two or three on a Chicago stage somewhere. And after 34 years as a critic for Booklist — the book reviewing magazine published by the American Library Association — she was just named its editor-in-chief.

Seaman grew up in Poughkeepsie and left to study art in Kansas City: “‘Where the hell is Kansas City?’ I wondered, like any good New Yorker,” she said. However, she didn’t have a clear vision of herself ever being an artist. She likes to say she’s an impractical person. She graduated college without plans. “I thought I would stop through Chicago, see friends, what it’s like here. I never left.” That was the late 1970s. She worked in libraries and for the nonprofit (and long gone) Book Market bookstore in Lakeview. “I knew books were a world where I could be happy. Some people follow the money, and no, I followed the books.”

Except in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Chicago literary scene was stagnant to nonexistent. “There wasn’t much when I arrived. There were really few writers hanging around. There wasn’t big reading series or festivals of important authors like we have today. I didn’t know many Chicago writers but when I started researching them, there were so many. I read them all and I started to track some of them down. When I started the radio show, I invited them on to the show, and I got an Illinois Arts Council grant.”

Her memoir itself — which recounts pieces of this — is a decent marker of how vibrantly the book community transformed in Chicago since she’s arrived. “River of Books” is published by Ode Books, which is an imprint of Hyde Park’s Seminary Co-op, which itself became a not-for-profit bookseller in 2019. Seminary Co-op Offsets is also an imprint, but of Northwestern University Press. Ode is published through a partnership with Prickly Paradigm Press, a small local press founded in 2002. Anyway, the point is, that rich of a book community, never mind a publishing network, wasn’t here in 1979.

She began writing for Booklist in 1990, and despite other duties at the magazine now (which went all-digital during the pandemic), she reviews regularly. She is known for taking on solemn epics, even though Booklist reviews are only about 200 words each.

“It’s important to me to keep (reviewing),” she says. “I’ve written thousands of reviews. It never gets easier. It might even get harder. I tell myself ‘Don’t be a hack … dig deeper.’”

Even worse, she’s a recommender. She is not one to tear down, which is easier. She wonders how many books one person can read about a flooded world — a literary sub-sub genre for a while now — but rather than trash a book she would hate, she avoids it. She reads mostly at night and on weekends; her go-to Chicago bookstores are Book Cellar and Women & Children First; and sorry, Seaman doesn’t listen to audiobooks.

“I am ambitious creatively but not materially,” she says. “I live simply. Again, it’s just a wildly impractical career. Everything I have ever done is not for profit. I don’t have a commercial bone in my body. I must say, I have been approached about different kinds of jobs (that pay better). I’ve even gone on the interviews. And I always left thinking: ‘No, I would not survive in that environment!’ When students ask me how I managed to do everything that I do now, I tell them …” She holds up her hands, as if utterly confounded.

“Look, I hunger for books, I don’t have children, but I have to support myself. I make it work by living simply. People ask how someone can do that. I’ll just say: ‘Pure need.’”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com