Most Americans take electricity for granted. They know the lights will come on when they flip the switch because their grid connection is secure and reliable. But the same can’t be said for Native American tribal communities, many of which are rural and have limited access to electricity, or none at all.

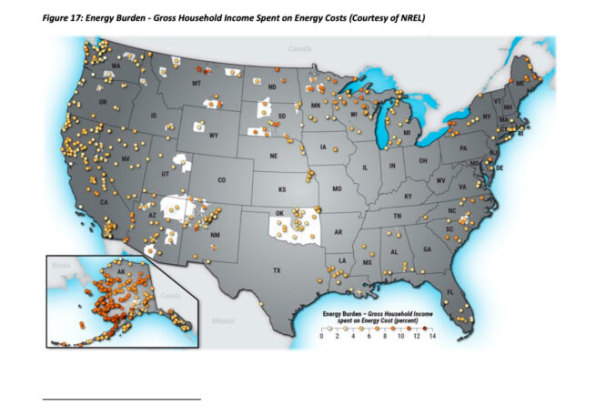

The Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy estimates that 21% of Navajo Nation homes aren’t electrified. For the Hopi Tribe, it’s 35%. And of those homes that do have electricity, 31% report monthly outages. Because these communities also have disproportionately high poverty rates, they also spend more of their earnings on energy costs.

The Biden administration is taking a step toward changing this, announcing earlier this week that the DOE has chosen 17 clean energy projects from a pool of applicants to receive a slice of $366 million. The projects are dotted across 20 states, and aimed at bringing reliable green energy to rural and remote areas. Crucially, all but five of the projects will serve tribal communities.

“This is the largest amount that the Department of Energy has awarded to tribes for energy projects,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said.

No two projects are the same, and each caters to the unique needs of the region being served. For example, one initiative slated to receive $26 million will install solar panels and battery storage systems so that eight remote Alaskan tribal communities can tap into microgrids for their electricity needs, instead of relying solely on expensive and dirty diesel. The end goal is to develop Alaska’s “largest tribally owned and operated independent power producer.”

In Washington state, $32 million will go toward converting existing irrigation canals into solar and micro-hydropower irrigation systems that can conserve water while providing renewable energy to the Yakama Indian Reservation.

The announcement comes at a tense moment in relations between the administration and Native American communities. Biden’s sweeping plan to boost renewables has faced pushback, and even legal challenges, from tribes that say some projects encroach on sacred land. In Nevada, for example, a Biden-approved lithium mine would provide essential components for electric vehicles, but it could also disturb cultural sites and deplete groundwater. Native Americans in Arizona are worried about how a massive clean energy transmission line will affect community landmarks.

“There’s a bit of a rising trend of more and more renewable energy development happening and tribes being caught in the middle or expected to have no issues with it because it supports the ‘green revolution,’” Wesley Furlong, an attorney for Native American Rights Fund, told E&E News.

These new clean energy projects may be different, though. For one thing, many of the applicants are members of local tribes seeking money for projects they can implement and oversee, and that will benefit their communities financially. The tribally owned power producer in Alaska, for example, will be overseen by a board of tribal leaders, and is expected to net $150,000 annually to be distributed among tribal governments. The Washington state hydro project team “plans to build solar panels on land that the Tribe knows does not risk disturbing cultural resources, providing a replicable solution for responsible solar siting.”

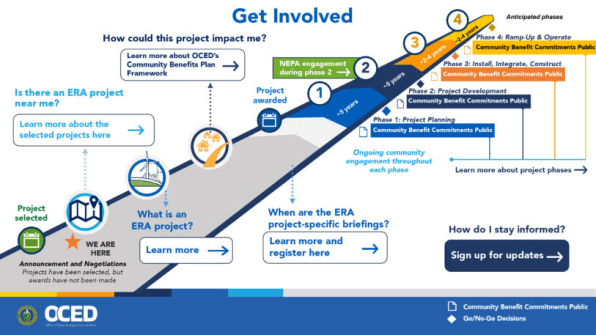

And these projects won’t be rolled out quickly. Some may not go ahead at all. Each applicant must submit a Community Benefits Plan demonstrating that local stakeholders will have a say in how the project affects their lives. They’ll also undergo a negotiation process with the administration’s clean energy office before funding is in the bag. Once it is, the start-to-finish timeline for the projects is between 14 and 18 years, and most will need additional funding to reach the finish line. Who knows what will become of them if a less-climate-minded administration takes the White House in November.

“What these announcements do is they build hope for communities,” Chéri Smith, president of the nonprofit Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy, told the Associated Press. “Translating these ambitions into tangible outcomes—we still have a ways to go.”