William “Craig” Kight hopes the second time through Lake County’s Veterans Treatment Court will be his last.

“They all taught us to drink when in the military,” said Kight, 51, of Merrillville, a Georgia native and former Marine. “Alcohol has always been my go-to.”

His latest OWI in 2022 landed him back in the program. Then, his son found him on Christmas Eve after he drank a bunch of vodka, he said. This time, he’s had his longest stretch of sobriety since he was a teen. He’s been able to mentor others as he wraps up.

He was one of 21 graduates Wednesday as vets court marked 10 years.

Jason Zaideman, Kight’s program mentor and head of Operation Charlie Bravo — formerly Operation Combat Bikesaver — said it would take a while to articulate the changes he believes will stick.

“He’s done,” Zaideman said.

In a decade, the program has had about 300 graduates, Judge Julie Cantrell said in an earlier interview. The program currently has about 86 veteran mentors.

“It’s the best thing I do,” she said.

It’s considered a “problem-solving court” — akin to Lake County’s drug treatment court, or therapeutic intervention/mental health court. The goals are similar — look at underlying causes, intervene with services and give them a chance to avoid a felony and stay out of prison.

Veterans spend 18-24 months getting regular drug screenings, a mentor, and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs services, if needed. A lot of people they typically see are dealing with drug charges, OWIs or “acting out” during an arrest, she said.

“They have to admit they screwed up,” Cantrell said.

The program sets a limit — accepting those charged with non-violent crimes, up to Level 2 felonies. They can accept Level 2 violent felonies on a case-by-case basis, if the spouse requests it, Cantrell said. It bars people charged with violent crimes, including murder, Level 1 felonies and crimes against kids.

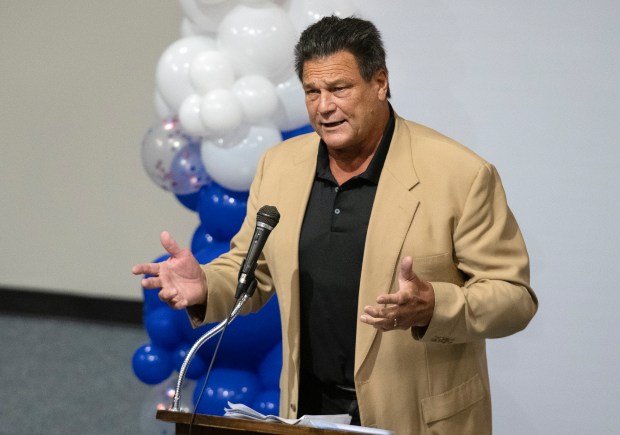

“At the end of the day, we’re all here because we’re not perfect,” said Chicago Bears Hall of Famer Dan Hampton, who faced an OWI arrest in 2021. He volunteered as the keynote speaker and spoke about his football years.

Others faced different life challenges.

Cantrell said on stage Michael Koble was shot defending his sister in a domestic dispute. Since then, he’s bought a house and is close to finishing a nursing degree. The latest OWI bust in 2022 brought him to the program, he later said.

Meanwhile, his sister’s estranged husband dislocated her jaw. It was the last straw. Koble went to the house and slashed his tires before the man shot him.

“It was a long road,” Koble, a former Marine, said of his time in the program for the OWI. Without its support, he’d “probably be in jail.”

mcolias@post-trib.com