Every Father’s Day, the world is treated to stories about phenomenal dads.

Men who sacrificed for their country, men who advanced science or society, men who served on boards, volunteered or changed the world — all while being dads.

Of course, these fathers deserve every accolade. But so do the bootstrap dads who maybe started with nothing, who maybe didn’t finish high school, and whose definition of heroics was to simply work hard, dream big and learn from their mistakes.

My dad was a worker, a hard worker. Not because he enjoyed truck driving but because his family needed every dime, and then some. He always took the overtime and, often, had a side gig on weekends.

Most of my early memories of my dad are of him leaving for work or coming home exhausted. He always wore a cap and he always carried a thermos. He was tired, even in his 30s.

It seemed he was always toiling at something and brow-beating us to do the same. Much the way parents today bury their kids in sports or music activities to keep them from walking on the wild side, he buried us in work.

How we handled our work spoke volumes about our character. If our task was to sweep the floor, we swept it with gusto.

He’d wake us early on Saturdays to clean the house or the garage or help him repair whatever damage a houseful of kids had caused that week. There was always something to be done. And, yes, when there wasn’t time to do that work right, there was always time to do it over.

While my friends were lounging in front of TV cartoons or out riding their bikes, we were working. Even when he wasn’t home, there were chore lists to be completed.

Sometimes we hated him for that.

But every now and then, he’d call us to pile into the car because we were heading to Playland or the roller rink or the zoo. He insisted we have a swing set, a dog and a backyard pool, even though he really couldn’t afford any of it.

After my grandmother moved to Florida, we began annual treks to Daytona Beach. A few times, my dad organized a caravan of friends and relatives — a fleet of station wagons — who made the journey south, stopping at Hen Houses, Lookout Mountain and Rock City.

I loved those trips. Fun seems so much more restorative when it’s sandwiched between tasks.

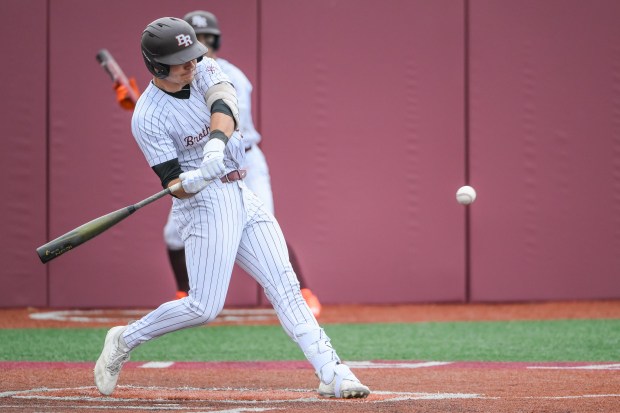

As soon as we were old enough, he began to nag about the importance of paid work. All six of his children were employed by age 15.

It seemed we were often berated for not working hard enough. “You can’t leave at 9 and get there at 9,” he’d say. Or, “Don’t do extra, you might make something of yourself,” which of course implied we weren’t enough already.

For most of my youth, I resented what seemed like the weight of the world on my shoulders. Much later in life he confessed that work was the only way he knew to keep us from getting into trouble, to keep us from repeating some of his mistakes.

Once, during my turbulent adolescence, he caught me at a local park with some questionable friends, some of whom had sneaked beer out of their homes. He had no problem breaking up the group, embarrassing the heck out of me and threatening to rat out each of my buds.

I was mortified. Later, he came to my room, sat down and told me about some of the horrors he’d seen happen to people who were careless.

He told me about his dream for me to go to college, to “make something of myself.” He also told me then that he’d once had dreams too. That he wanted to someday live in a big house on a hill. Stupid mistakes, he said, get in the way of your dreams.

He said he knew I was smart enough to not let that happen but he wondered if I was strong enough to not let others influence me to the extent that it would happen anyway. True friends, he said, elevate you, they make you better and they absolutely keep you safe.

It made me think. And that is the greatest gift my father gave me — the ability and the willingness to be thoughtful.

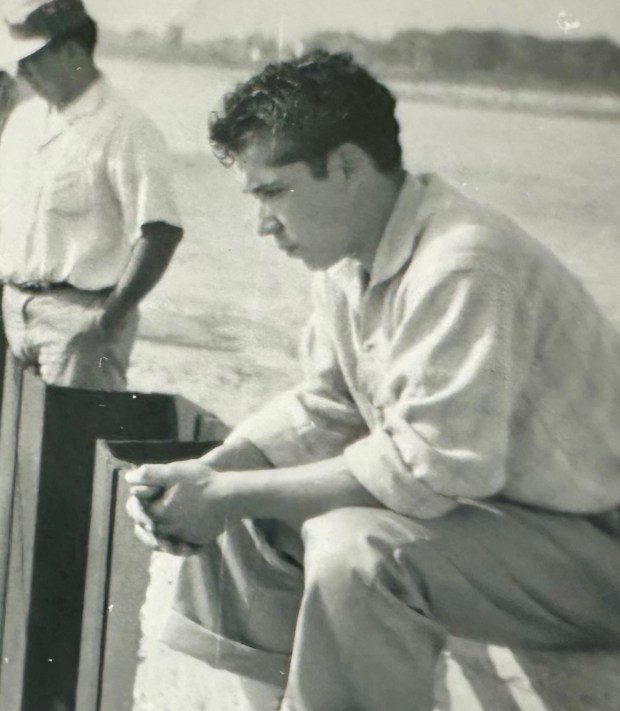

Growing up, my father often got lost in the mix of his very large family. He wandered onto questionable paths early. He was a still a child when he began raising a family of his own.

He often fumbled. But he also said, “Smart means learning from your mistakes.”

He was wise in that sense. He also was brave and funny and compassionate and never, ever above apologizing. He was often a mediator for family troubles, even standing up to his own brother during the elder man’s bouts of alcoholic rage and abuse.

When my mother was ill and in a nursing home for nearly a year, he was at her side every single day, even after his car was towed because he’d parked in a snow zone.

He was quietly generous, often when he couldn’t afford to be. Again and again, he made room in our tiny bungalow for relatives in need. After he passed, I found stacks of receipts of donations he made to the church, to St. Jude Children’s Hospital, to the American Cancer Society, to local politicians and to family members.

Hard as he worked for so long, he never got that big house on a hill. His final chapter was spent in a nursing home, a cold, impersonal place where many of the employees not only didn’t care about him, they didn’t seem to care about their work, which for him was the greater sin.

I wish there could have been a better way. I wish he’d made an end-of-life plan and that immobility hadn’t forced his hand. I wish he’d gotten his dream house.

Mostly, I wish the world had not been such a hard place for him. But I am oh-so-grateful that he made it softer for me. I had opportunities my father only dreamed of, partly because of luck but mostly because I knew how to work hard.

My dad did what every generation of parents tries to do: He elevated the opportunities for those who came next.

He was a good dad.

And that’s deserving of praise.

Donna Vickroy is an award-winning reporter, editor and columnist who worked for the Daily Southtown for 38 years. She can be reached at donnavickroy4@gmail.com.