Every date, name and location we publish in this newsletter is checked and rechecked against Tribune archives and other reference materials to make sure it’s accurate. It’s a time-consuming process that has led us down more than a few rabbit holes. But each little investigation is necessary — we don’t want to pass along information that’s misleading or flat-out wrong.

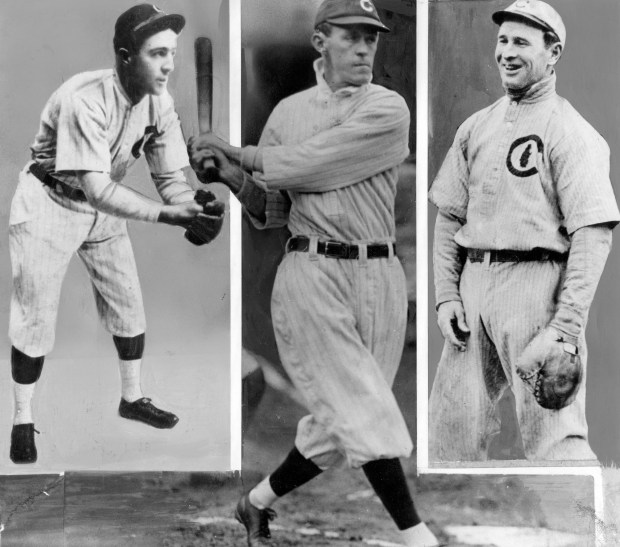

Sometimes, as a result of our fact-checking process, we have a “Eureka!” moment — we debunk a piece of conventional wisdom about Chicago history. It happened just last week. The Chicago Cubs infield trio of shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers and first baseman Frank Chance (of “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon”) was the best double play combination of the day. But many reference the trifecta’s first double play turned as Sept. 15, 1902. After looking back at the Tribune’s archival stories we discovered it actually happened a day earlier — Sept. 14, 1902. MLB’s official historian John Thorn confirmed the validity of our find.

On other occasions, we’ve found the Tribune itself has started a rumor or passed one along. (Yikes.)

After chatting with our colleagues and searching the Tribune archives, we’ve assembled a list of items that might change what you think you know about the city’s past. But we’re always looking for more! Have an idea? Email us.

‘Founding’ of Chicago

Commonly held belief: Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable or John Kinzie discovered the area we now know as Chicago and were its first citizens.

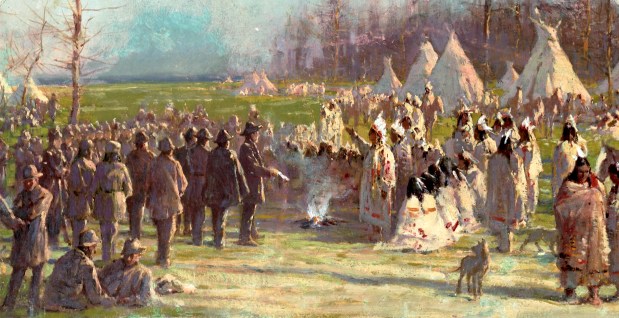

What really happened: “While it’s often said that Chicago was inhabited by ‘Indians’ prior to the European explorers’ arrival, this simple statement overlooks a more nuanced reality — that at least a dozen distinct Indigenous nations used this place in myriad unique ways,” Rose Miron, former director of the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library in Chicago, wrote in the Tribune in November 2023. “Chicago was a center for meeting and trade, and at some points in history, it had more permanent village sites. Other tribal nations came into the area seasonally to harvest food sources or traveled through the portage to access the Great Lakes or the Mississippi River.

“Even after the first land cession in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, the majority of the land we now call Chicago remained under Native control for several more decades, particularly by the Anishinaabeg, a confederation of Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Odawa people, who were the primary Indigenous nations in Chicago by this time. Few non-Native settlers lived in the area, and those who did depended on Anishinaabe people to survive.”

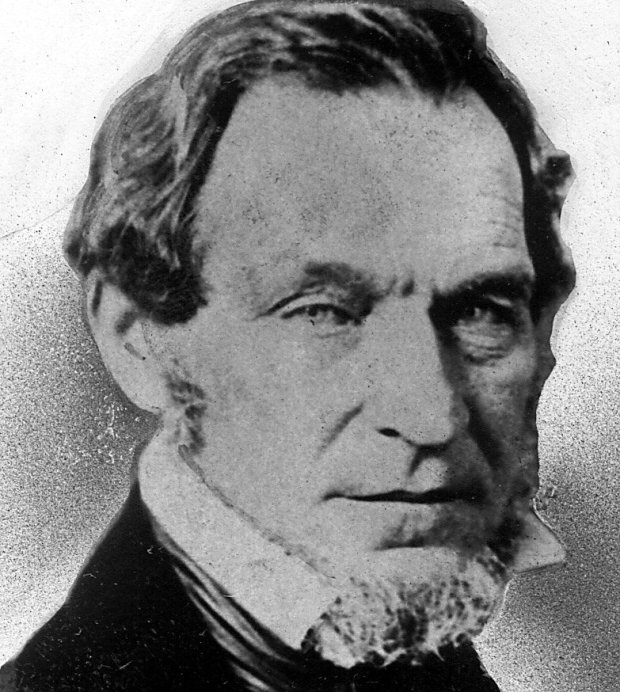

John Kinzie

Commonly held belief: This is a photo of the same Kinzie (mentioned in the item above) who is responsible for the first documented homicide in Chicago.

What really happened: The Tribune ran a story in 1940 about Kinzie, and included a photograph. The newspaper did the same in 1961, 1962, 1968, 1989 and 1995.

In 2017, a correction was needed after Tribune photo editor Marianne Mather caught the mistake: The Tribune claimed the man in the photo was Kinzie, but it was actually his son, John H. Kinzie. It’s not the first time Mather has used her detection skills to find rare gems in the Tribune archives. She also found an arrest photo of a young Bernie Sanders and uncovered rarely seen photos of the Eastland Disaster.

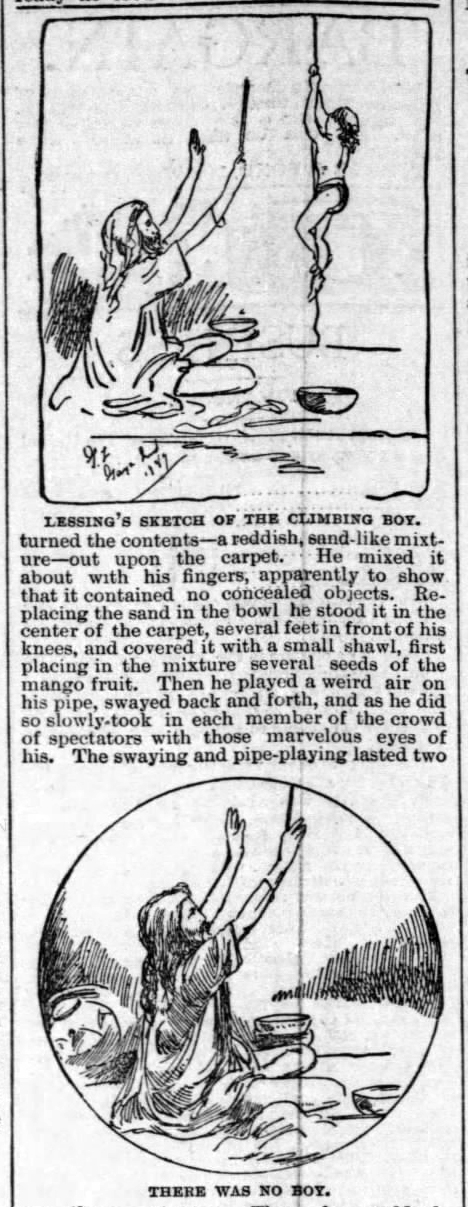

The Indian Rope Trick

Commonly held belief: A young boy in India performs a trick where he climbs up a mysteriously suspended length of twine and disappears upon reaching its top.

What really happened: Peter Lamont, author and magic historian, discovered this yarn began in the Tribune on Aug. 9, 1890. He published his results in the 2004 book, “The Rise of the Indian Rope Trick: How a Spectacular Hoax Became History.”

The Tribune eventually admitted in print that its story was intentional hokum. The suspected writer, John E. Wilkie, was neither fired nor hurt by the ruse — on the contrary, he made a surprising career leap and later was named head of the U.S. Secret Service.

Catherine O’Leary

Commonly held belief: There are several versions, but the most common one is this — Catherine O’Leary went into the barn on the dry Sunday night of Oct. 8, 1871, with the lantern to milk one of her cows for oyster stew. O’Leary left the lantern in the barn and the cow kicked it over and started the fire.

The early versions placed blame on O’Leary, calling her old and drunk, though she was the mother of several small children.

The Great Chicago Fire destroyed 17,450 buildings. Here are six that survived and still stand today.

What really happened: We’re not sure who is responsible for starting the conflagration, but O’Leary and her infamous bovine were exonerated by the City Council Committee of Fire and Police on Oct. 6, 1997.

H.H. Holmes’ ‘Murder Castle’

Commonly held belief: Differing accounts claim that Holmes may have had hundreds of victims who were tortured and killed within the building’s network of secret rooms.

What really happened: The tales remain largely sensational tabloid fabrications. Local historians and researchers have cast doubt on many of the most outlandish actions attributed to Holmes and his 63rd Street three-flat, including the popular theory that he lured and discreetly killed dozens of victims and disposed of them in the basement of his property.

Holmes’ former building at 610 W. 63rd St., which initially had a drugstore on the ground floor and rooms on the second floor before a third story was later constructed, did indeed have secret rooms and a walk-in vault that was “mostly” soundproof. But it likely was used to conceal stolen furniture rather than murder, experts say.

“He did kill nine or 10 people, but it wasn’t hundreds and hundreds. It wasn’t in a hotel, and it wasn’t World’s Fair patrons,” said author and Chicago tour guide Adam Selzer, whose 2017 book “H.H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil,” sought to demystify the killer behind the legend, using official records and documents.

“He was a swindler, first and foremost, who partly through his own confessions, became a new American tall tale,” Selzer said.

The ‘traffic jam’

Commonly held belief: This photo by Frank M. Hallenbeck circa 1909 is often cited as depicting a traffic jam at the intersection of Dearborn and Randolph streets in Chicago. It was used several times through the decades in Tribune stories, which said it was an actual clogged thoroughfare.

What really happened: While this intersection was often cited for being one of the most congested in the Loop during the early 20th century, what’s actually shown is an experiment. The city’s street traffic committee studied what happened when police officers stopped directing street cars, buggies and automobiles at busy intersections, including this one. Chicago police Capt. Charles C. Healey even visited major cities in England and France to observe how their streets were modified in order to prevent crowding and stoppage and instituted some of their ideas to help make Chicago’s streets passable.

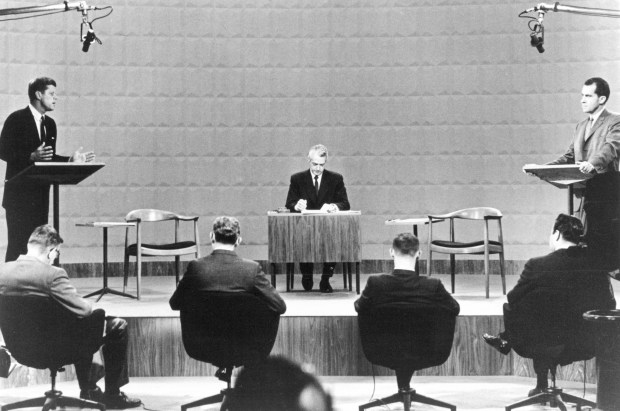

The ‘winner’ of the first televised presidential debate

Commonly held belief: If you listened to it on the radio, Vice President Richard Nixon won. If you watched it on CBS television, as many more seemed to do, Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy Kennedy won.

What really happened: Held at WBBM-TV studios, 630 N. McClurg Court, on Sept. 26, 1960, Nixon and Kennedy squared off in the first presidential debate shown on TV. (The studios were demolished in 2009, and the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago opened at the site in 2017.) Yes, Nixon appeared sweaty while Kennedy appeared poised and relaxed.

But there’s no evidence that the medium — TV or radio — made the difference among voters, according to a paper published in 1987 by two Colorado State University faculty members.

(Thanks to Mark Jacob, former Tribune Metro editor and Stop the Presses newsletter curator, for suggesting this item, the 1909 traffic jam and the following one.)

Daley ‘steals’ votes for Kennedy

Commonly held belief: The Democratic machine secured the presidency for JFK by conjuring up ghost voters and stuffing ballot boxes in Cook County.

What really happened: The truth is far less dramatic —Illinois didn’t matter during the 1960 presidential election. Kennedy carried the electoral vote 303-219, a margin of 84 votes. Illinois had 27 electoral votes. Even if the Land of Lincoln had handed those electoral votes to Nixon, Kennedy still would have won the White House.

Daley and the Democrats delivered a huge Chicago tally for Kennedy, who carried the state. But Daley was probably driven more by his great desire to defeat Republican Cook County State’s Attorney Benjamin Adamowski. Adamowski jumped to the GOP after he lost the 1955 Democratic mayoral primary to Daley, and as the county’s top prosecutor he had been nothing but trouble for the machine. He lost the 1960 election to Democrat Dan Ward, the former dean of the DePaul University law school who ran for the Democrats.

Death of the Spilotro brothers

Commonly held belief: In June 1986, Anthony Spilotro, 48, and his brother Michael, 41, were beaten with baseball bats then buried alive in a northwest Indiana cornfield.

What really happened: Contrary to what was depicted in the 1995 film “Casino,” the brothers were driven on June 14, 1986 to a Bensenville home, where Michael thought he was going to become a “made member” of the Outfit. Instead, they were beaten with fists, knees and feet in the home’s basement before their bodies were driven to the cornfield and buried. Dental records were used by their brother Patrick Spilotro, a dentist, to identify the bodies.

The details came out during the 2007 “Family Secrets” trial, which Tribune editor Jeff Coen wrote about in the 2009 book, “Family Secrets: The Case That Crippled the Chicago Mob.”

First nighttime baseball game at Wrigley Field

Commonly held belief: The Cubs played under the lights for the first time on Aug. 8, 1988.

What really happened: Starting pitcher Rick Sutcliffe was nearly blinded by the thousands of flashbulbs that went off as he delivered the first pitch on Aug. 8, 1988. Perhaps that was why Philadelphia Phillies outfielder Phil Bradley deposited Sutcliffe’s fourth pitch into the bleachers.

Then, with the Cubs leading 3-1 in the fourth inning, the rains came. Not a light drizzle, but a downpour. After a two-hour rain delay, the game was called, obliterating it from the record books. “This proves that the Cubs are cursed,” said one fan, as she ran from the ballpark. The Tribune editorialized, “Someone up there seems to take day baseball seriously.”

On Aug. 9, 1988 —the first night game in Wrigley Field history that actually counted — the Cubs hit the New York Mets with four runs in the seventh inning and held on for a 6-4 victory before 36,399 very noisy people.

“It might have been louder last night,” said Mark Grace, who drove in one of the runs in the decisive seventh. “But that’s the loudest for a complete game that I’ve ever been associated with.”

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

Thanks for reading!

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group, stay current with Today in Chicago History and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Kori Rumore and Marianne Mather at krumore@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com