It seems every neighborhood in Chicago is said to have the spirit of Al Capone or John Dillinger roaming its streets late at night.

But since it’s spooky season, we thought we would skim the Tribune’s archives for more ghostly tales. Here are a few that could be real, or not, but have caused Chicagoans to be scared about what goes bump in the night.

Chicago history headlines:

- A football fan’s Valhalla: Red Grange christened Memorial Stadium 100 years ago and became an Illini legend

- Oct. 14, 1945: Chicago Cardinals snap losing streak

- Oct. 17, 1931: Al Capone convicted of tax evasion

- Oct. 17, 2021: Chicago Sky win their first WNBA Championship

Clarence Darrow

The legendary attorney, who secured life in prison for his clients Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, died March 13, 1938, at age 80.

Just six years earlier, he and two magician friends made a pact that the first of the trio to die would attempt to communicate from beyond the grave. In this case, Jackson Park near the Museum of Science and Industry — where Darrow’s ashes were scattered. Today, the footbridge over the park’s lagoon is named in his honor. There’s no evidence Darrow ever answered the call, yet some believe his spirit never left Chicago.

Tour guide and ghost hunter Richard Crowe told the Tribune about his experience on Halloween night in 1995. He was leading a tour of Jackson Park when the group encountered a man in a top hat. Several of the participants decided to chase the figure.

“I wasn’t sure if it was a hoax,” Crowe told the Tribune in 1997. “But the two men get within a few feet of the old guy, and they freeze. Now here’s an old guy out walking in the park with two people running after him, and he is just ignoring us. You figure someone real would have at least walked a little faster. But this guy looks out over the water, and then just walks away.”

And the tour members? “They said they were literally frozen with fear and were unable to get any closer.”

Resurrection Mary

Crowe, who died in 2012, was also interested in the captivating tale of the Southwest Side’s signature spirit.

There are two versions: In one, a young woman who’d been dancing in the 1930s at the Willowbrook (then the O. Henry) Ballroom, which was gutted by a fire in 2016, has an argument with her boyfriend and decides to walk home. On her way back to Chicago, she is hit by a car and killed. In the other version, the girl leaves Willowbrook after an evening of dancing but is killed when the car she is riding in, being driven by her father, is hit by another car. Both versions end with the girl being buried at Resurrection Cemetery in Justice, hence the nickname.

Many claim the specter of a young woman in a flowing white dress appears along Archer Avenue near the cemetery, asking for a ride. Those who pick up the mysterious hitchhiker, however, are startled with fear when she suddenly vanishes.

Seaweed Charlie

“Lake Michigan is chock-full of things that go splash in the night,” Frederick Stonehouse, author of “Haunted Lake Michigan,” told the Tribune in 2007.

And planes are part of the lore. On Sheridan Road, directly across from Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, hundreds of people have reported seeing the ghost of “Seaweed Charlie,” according to author David Cowan.

“He was a naval aviator whose plane crashed in the lake during training exercises in 1943,” Cowan said in 2007.

The plane piloted by Charlie, thought to be Herbert Brown, was recovered, but his body was not. He is said to be seen climbing over the rocks out of the lake, his flight suit dripping and covered in weeds as he drags himself across the road to the gates of the cemetery, where he disappears.

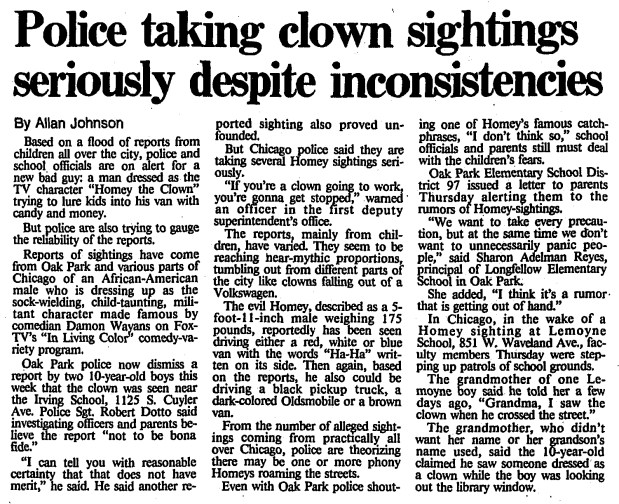

Homey The Clown

Just before Halloween in 1991, children around the city and Oak Park reported sightings of a 5-foot-11Black man weighing 175 pounds and dressed up as “Homey the Clown,” who was a sock-wielding, child-taunting character portrayed by Damon Wayans on the popular Fox comedy show, “In Living Color.”

Pre-teens told police and school administrators the figure attempted to lure them into his van by offering them candy and money.

Suburban officials didn’t believe these reports, by Chicago police still took them seriously — though no one was ever singled out as a suspect or arrested.

George Stickney House

The Bull Valley police headquarters in central McHenry County has a unique feature — no corners. The building on Cherry Valley Road was constructed in the 1840s by George Washington Stickney, an early settler of the area who arrived from New Hampshire. He and his wife Sylvia were spiritualists who believed that evil lurked in corners. They conducted seances from their home and held grand parties in its upstairs ballroom, which featured the county’s first piano. Several of the Stickneys’ 11 children died there. In 1978, the house was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Subsequent owners have claimed dogs bark at nothing and other strange occurrences have happened in the Stickney house, which was eventually donated to the village of Bull Valley after years of decay.

Today it’s the headquarters for the village’s police force.

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com