Feb. 29 appears on the calendar once every four years — an aid to anyone who has ever wished for just a little bit more time. But why does it happen?

Freshly retired WGN-TV chief meteorologist Tom Skilling explained the extra day’s importance in an “Ask Tom” column from 2009: “A tropical year, defined as the time between successive vernal equinoxes, is 365.2422 days — so adding a leap day every four years keeps the alignment differences between the calendar and the seasons fairly insignificant.”

Through the decades, Chicagoans have found ways to turn leap day into an unofficial holiday. For traditionalists, it’s remembered as “Bachelor’s Day,” when women could ask men for their hands in marriage. In Aurora, unwed women took over local government on Feb. 29 from the 1930s until 1980 and “arrested” unmarried men who refused to propose marriage — offering them a reprieve if they donated to a charitable cause.

For others, it’s just another day. But, as you’ll see below, there’s no such thing as an ordinary day in Chicago. Here are some memorable events from Feb. 29 in the city’s history.

1940: Comiskey family keeps the White Sox

J. Lou Comiskey, the only heir of Chicago White Sox founder Charles Comiskey, inherited the team after his father’s death in 1931. When the younger Comiskey died of a heart attack complicated by pneumonia in 1939, the family’s ownership of the team was challenged.

In his will, J. Lou Comiskey expressed a desire for the team to remain in the family after his death. The Comiskey family owned all but 50 shares of the White Sox at the time and had no debt. But First National Bank of Chicago, which was the executor of J. Lou Comiskey’s estate, sought permission from probate court to sell the club anyway claiming ownership of the team involved too much financial uncertainty.

After a two-hour discussion in court on leap day 1940, a judge denied the bank’s petition and allowed the Comiskey family to keep ownership of the White Sox. They would retain the team until Bill Veeck announced he had become the majority owner in early 1959. Veeck actually owned the Sox twice — from 1959-61, and in 1976-80, when he returned after discovering that the franchise was near bankruptcy and was to be moved to Seattle.

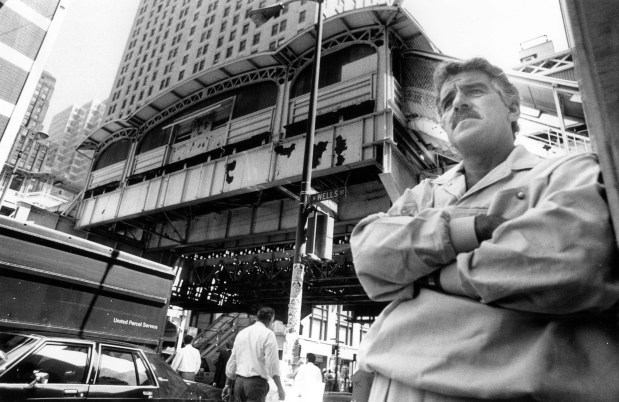

1944: Dennis Farina born

Born in Chicago on Feb. 29, Farina was the fourth son and youngest of the seven children of Joseph and Yolanda Farina. The father was a doctor, the mother a homemaker, and they raised their kids in a home at 549 W. North Ave. in an area that was then a working-class neighborhood with a broad ethnic mix predominated by Italians and Germans. Farina became a police officer in the city for 18 years — rising to the rank of detective.

“When I was younger I watched all the detective shows,” he told the Tribune in 1998.

A fan of TV police shows is all Farina might have been had he not hooked up around 1980 with “Miami Vice” producer Michael Mann, who was a friend of a friend.

As an actor, Farina was famous for his work in such films as “Get Shorty,” “Saving Private Ryan” and “Midnight Run,” and in television shows such as “Crime Story” and “Law & Order.” He died in 2013 in Scottsdale, Arizona, after suffering a blood clot in his lung. He was 69 — or about 17 in leap years.

1952: A birthday celebration — for two

In math, four never equals one.

But for a select group of people whose birthdays fall on Feb. 29 — leap day — and who celebrate birthdays every four years, the impossible becomes possible.

For the Leipis family, three was the magic number. As in, Evelyn Leipis gave birth to her third set of twins — two girls.

1960: First Playboy Club opens

Known as the Playboy Key Club, it opened on leap day 1960, in a building leased from Chicago Bulls and Blackhawks owner Arthur Wirtz. Mabel Mercer was its first starring act.

The club was inspired by another Chicago establishment called the Gaslight Club, which required its members to carry a key for entry and featured a waitstaff of women decked out in sequin-trimmed velvet corsets and little else.

Ads in the Chicago Tribune and other publications said Playboy was offering a “great opportunity for the 30 most beautiful girls in Chicagoland” to work as Playmates at the club. Nearly 17,000 people visited it in its first month of operation.

The Chicago club moved over the years, ending up at Clark Street and Armitage Avenue, before finally closing for good in 1986.

1980: Record snow falls (unofficially)

A storm that came off Lake Michigan dumped 6 to 9 inches of lake-effect snow in two trips across the Loop, but in other parts of the city less than an inch fell. The high temperature climbed to just 17 degrees.

“You’d have a blizzard on one street while a block away the sun was shining,” said David Dowd, a National Weather Service meteorologist.

It would have been the largest snowfall on record in Chicago for Feb. 29, but the city’s official recording site had moved less than two months earlier from Chicago’s Midway Airport to O’Hare International Airport. Snow accumulated at Midway on this date in 1980, but less than half an inch fell at O’Hare.

Here are other weather statistics for Feb. 29. in Chicago:

The warmest: 65 degrees, breaking the mark of 54 degrees, set in 1932.

The coldest: Minus 3 degrees, set in 1884.

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

- And, catch me Monday mornings on WLS-AM’s “The Steve Cochran Show” for a look at “This week in Chicago history”

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com