For those who seek clemency for a federal conviction, the process starts just like a job search — with an application.

It’s a complicated system that makes it difficult to track how many people in Illinois and more specifically the Chicago area have had their offenses forgiven (pardoned) or have been released from prison early due to a president’s intervention without forgiveness for the crime (commutation).

That’s where the Tribune’s archives help. We reviewed the names of people who have received pardons or commutations going back to the 1950s. Here’s a look back at some of them.

Rod Blagojevich

President Trump, convicted of felonies himself, commuted the former Illinois governor’s 14-year sentence to about 8 years served on Feb. 18, 2020.

The decision came after Trump had repeatedly teased the idea of commuting Blagojevich’s sentence. Trump, a Republican, said the sentence against Blagojevich, a Democrat, was “a tremendously powerful, ridiculous sentence in my opinion.” Though the two were from different political parties, Blagojevich appeared on Trump’s “Celebrity Apprentice” TV show while Blagojevich awaited trial on the corruption charges.

Blagojevich was elected governor in 2002 and served until 2009 when he became the first Illinois governor in history to be impeached and removed from office. The impeachment occurred after Blagojevich was arrested in late 2008 by federal law enforcement on a series of corruption charges, including attempting to sell the U.S. Senate seat once held by President Barack Obama. At Blagojevich’s first trial, he was convicted of lying to the FBI but the jury was hung on other charges.

At his second trial, in 2011, Blagojevich was found guilty on the more widespread allegations, including the Senate seat charges, trying to shake down a children’s hospital leader in exchange for sending money approved for pediatric services, and seeking a $100,000 contribution from a horse track owner in exchange for signing favorable legislation.

After being released from a federal prison in Colorado, Blagojevich returned to Chicago and proclaimed himself a “Trumpocrat.”

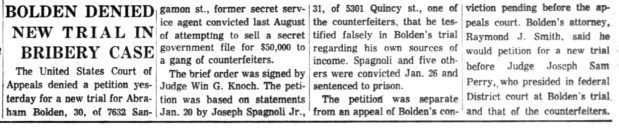

Abraham Bolden

Bolden, who became the first Black Secret Service agent to serve on the security detail for a U.S. president, was among 78 people granted pardons or commutations of their sentences on April 26, 2022, as part of President Joe Biden’s first use of his executive clemency powers.

Bolden, who’d warned about lax security practices around President John F. Kennedy, was charged in 1964 with attempting to sell a copy of a Secret Service file to a ring of counterfeiters.

Bolden, who earned a bachelor’s degree in music, held piano concerts to raise money for his defense. His first trial ended in a hung jury, and after he was convicted on Aug. 12, 1964, in a retrial, key witnesses said they lied at the prosecutor’s request. But Bolden’s request for a new trial was denied.

A longtime resident of Chicago’s South Side, Bolden served about three years in federal prison. He has long maintained his innocence and wrote a book in which he argued he was targeted for speaking out against racist and unprofessional behavior in the Secret Service.

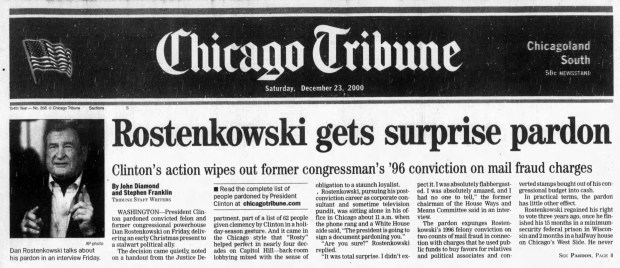

Dan Rostenkowski

The former congressional powerhouse was pardoned Dec. 22, 2000, in the closing weeks of President Bill Clinton’s administration.

The pardon expunged Rostenkowski’s 1996 felony conviction on two counts of mail fraud in connection with charges that he used public funds to buy favors for relatives and political associates and converted stamps bought out of his congressional budget into cash.

Rostenkowski was a U.S. congressman from 1959 to 1995 who was for many years considered one of the most powerful politicians in the U.S. as he headed the House Ways and Means Committee. In 1994, he was indicted on corruption charges for his role in the House Post Office scandal. Rostenkowski faced an array of charges, from ghost payrolling and using congressional funds to buy gifts for friends to trading in officially purchased stamps for cash at the House Post Office.

He lost his seat to an upstart Republican, and in 1996 he pleaded guilty to charges of mail fraud and served about 15 months in prison after treatment for cancer. He maintained his innocence throughout the rest of his life.

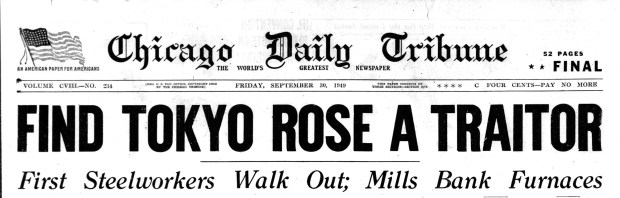

Iva Toguri D’Aquino (‘Tokyo Rose’)

Pardoned by departing President Gerald Ford on Jan. 19, 1979, Toguri had been living in Chicago for decades and quietly working at the mercantile store her father founded near Clark Street and Belmont Avenue.

Toguri’s name had been intertwined with the notorious label “Tokyo Rose” since World War II. Born July 4, 1916, in Los Angeles, the bobby sox and saddle shoe-wearing University of California, Los Angeles graduate enjoyed swing music and wanted to become a doctor.

Life took a precarious turn, however, in early 1941. An aunt in Japan was dying, so the 25-year-old woman went on the hastily planned trip (sans passport) — though she spoke no Japanese, had never been to Japan and had never met this relative. When the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Toguri was trapped with no identification to secure a passage home. She wouldn’t be with her own mother when she died in 1942 nor with her family when they were forced into an internment camp.

Job prospects in Japan were limited. She found work at Radio Tokyo and was quickly put on the air for an English-language show. “Zero Hour” was operated by Australian and U.S. prisoners of war under the direction of the Imperial Japanese government. Toguri was one of several female disc jockeys on the program — who were nicknamed collectively by U.S. forces as “Tokyo Rose” — but the only American citizen. She went by “Orphan Ann” — Ann was short for announcer and orphan to convey her situation.

Toguri was charged with broadcasting propaganda on Tokyo’s airwaves that toyed with the morale of American military personnel. No written or electronic recording of her supposedly subversive shows was presented at her trial. Testimony against her was weak. The Tribune said she was “the victim of the greatest post-war travesty on justice.” When Toguri became the second woman convicted of treason in the U.S., she was also labeled a traitor, stripped of her citizenship and sent to federal prison.

Interest in Toguri’s case was renewed in 1969 when she granted an interview with WBBM-Ch. 2’s Bill Kurtis. Tribune reporter Ronald Yates then revealed in 1976 that two witnesses were forced to tell half-truths and withhold vital information during Toguri’s trial.

Twenty-seven years after her conviction for treason, Toguri was pardoned.

Reynolds Wintersmith

President Obama commuted Wintersmith’s sentence on April 17, 2014.

At age 11, Wintersmith lost his mother to a drug overdose and was sent to Rockford to live with relatives who ran a drug house. Within five years, he joined the illicit trade with the Gangster Disciples, a decision that ended in 1994 in a stunning mandatory life sentence for the first-time, teenage offender. At the time he was sentenced, the federal sentencing guidelines gave judges no real leeway and a 2010 law did not give Wintersmith and other prisons like him retroactive relief.

A year after he received clemency, Wintersmith found a home in Chicago and, perhaps more impressively, a career. He became a counselor at a Chicago high school. He walked the halls in a sharp suit, teasing students with pet names, mediated minor fights and never shied from sharing his story.

“I have 21 years worth of things to talk to them about,” he said with a smile.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, Wintersmith also earned an associate’s degree and became a consultant.

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

Thanks for reading!

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group, stay current with Today in Chicago History and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Kori Rumore and Marianne Mather at krumore@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com