Paul Durica, director of exhibitions at the Chicago History Museum, continues his daily reading of the Chicago Tribune from 1924.

Want to follow along? Durica shares what he finds on his website, pocketguidetohell.com.

Here’s a look at five stories he discovered during February:

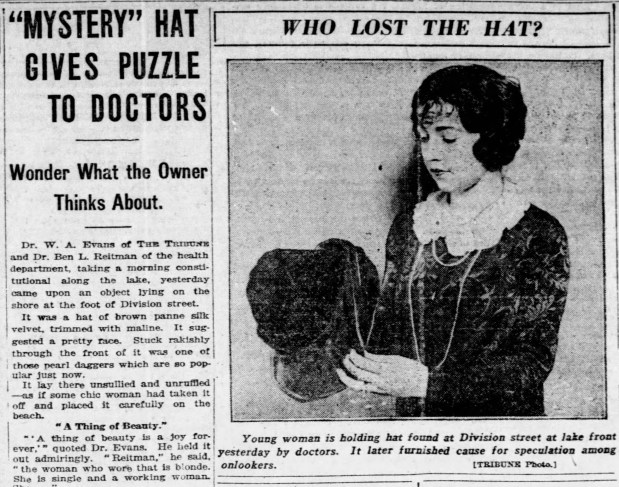

Feb. 2, 1924: ‘Mystery’ hat puzzles doctors

Health columnist W.A. Evans stumbled into a minor mystery while walking along the lakeshore at Division Street with Ben Reitman, physician to the hobos and denizen of the Dill Pickle Club.

Skid Row: A last resort, a place to disappear — or, for many, home

They came across a woman’s brown velvet hat laying “unsullied and unruffled” on the sand. This discovery prompted the men to turn detective and use the qualities of the hat to determine the character of its owner. Noting the pearl dagger pendant “rakishly” pinned to the front, Evans concluded she was a young, blonde, single, working woman. Perhaps not single but married, Reitman suggested, although he gave no reason for this conclusion. Had this woman walked into the lake and ended her life, as Evans deduced, or had the hat blown off her head while she rode on the top level of an open air motorbus, as Reitman maintained?

They brought the hat to the Tribune’s office where more speculations were made by journalists. A label on the lining led them all to the hat’s maker, who in a phone call remembered the owner as being a rather nondescript woman. Within a day, the mystery resolved itself when the owner, Mary Edna Cook, came forward, saying Reitman was correct — she had been on a bus near the lake when the hat blew off her head. She thought it lost forever. Cook worked as a secretary for the Sinclair Oil Co., in the news that week for its connection to the Teapot Dome scandal.

Feb. 3, 1924: ‘The Birth of a Nation’ shut down on opening night at Auditorium Theatre

A judge, who was seated in the audience among an estimated 4,000 people, disrupted the screening after determining the more than three-hour-long Civil War epic violated a state statute passed in 1917 that barred the showing of pictures that tend to engender race or class hatred. Police shut down the showing of the 1915 film.

For a few minutes the spectators believed the film had broken. Then the lights flashed on and the management announced, “The motion picture operators have been arrested. We shall have the chief of police before a judge in the morning for contempt of court,” the Tribune reported.

‘The Birth of a Nation’: A history lesson we cannot afford to miss

Police repeated the effort the next evening and then stood aside and let the film play while an injunction worked its way through the courts. (Yes, there was a time — not so long ago — when the police decided what movies Chicagoans watched.)

Mae Tinée, the pen name of the Tribune’s reviewer, called it “the greatest picture ever made.” But Tribune movie critic Michael Phillips said a century after the film’s release, “It is often painful to watch, even when its techniques and ambitions command attention, even now. The film is as accomplished and sophisticated visually as it is notorious and vicious thematically.”

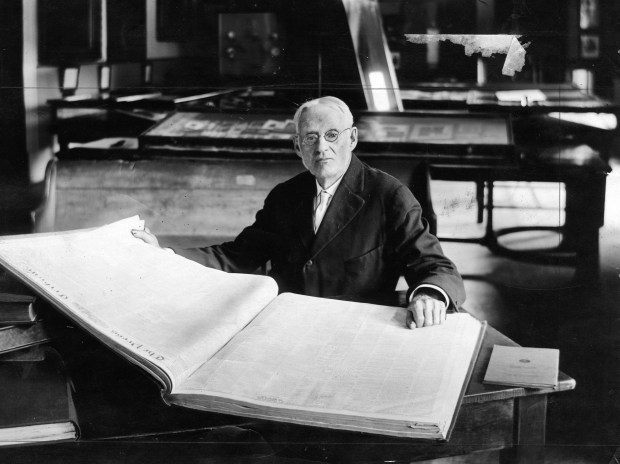

Feb. 10, 1924: Only living delegate of 1860 Republican National Convention recalls his unexpected vote for Abraham Lincoln.

Days before Chicago and the nation observed the 115th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s birth, 86-year-old Addison Procter — the sole surviving delegate to the 1860 Republican convention — told the “true story of Lincoln’s nomination for the presidency” at the city’s historical society. Procter had come to the Chicago convention from Kansas intending to support New York’s William Seward.

Vintage Chicago Tribune: How Chicago became the go-to city for political conventions

“Gradually it became apparent that the border states — between the North and the South — held the balance of power,” Procter told the crowd of 250 people. “They kept telling everyone they wanted a nominee born among them — one who understood them.”

That led to the nomination of the Kentucky-born Lincoln. After the talk, visitors had the opportunity to view the gray shawl Lincoln wore in New York when he made his famous Cooper Union speech, a whittling knife, a lock of hair and other artifacts.

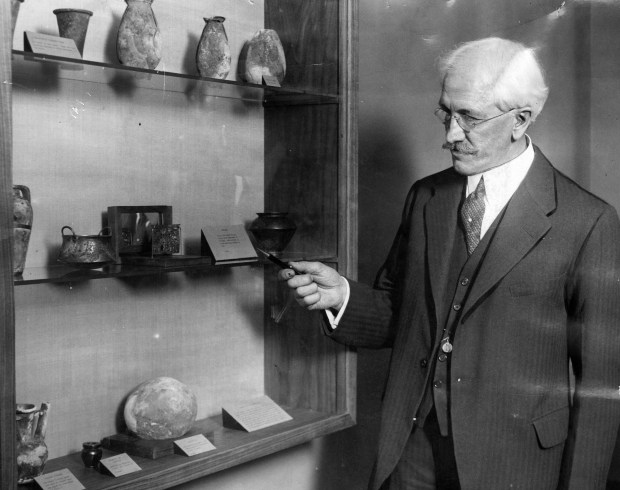

Feb. 12, 1924: A ‘gleaming, golden man’ uncovered in Egypt

The University of Chicago’s James H. Breasted was among those who witnessed the truth of a much deeper past revealed. Outside Luxor, in the Valley of the Kings of Egypt, within pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb, a story millennia in the the making neared its end when a system of pulleys lifted up the heavy pink sandstone lid of the inner sarcophagus holding the mummy case containing the ancient ruler’s body. The first to look inside was archaeologist Howard Carter, who had rediscovered the tomb in 1922.

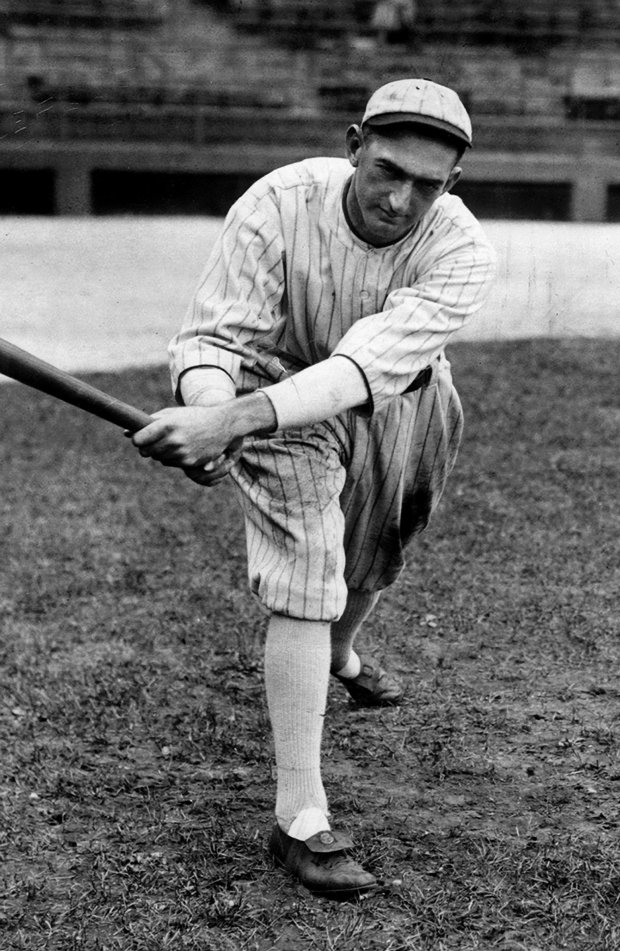

Feb. 15, 1924: ‘Shoeless Joe’ Jackson awarded back pay

A part of the past many Chicagoans preferred to forget resurfaced when a Milwaukee jury awarded Joseph Jefferson “Shoeless Joe” Jackson — a former White Sox baseball player disgraced by his believed involvement in the crooked 1919 World Series and banned from the sport for life — the pay that was owed to him for the 1920 season.

Flashback: How 8 White Sox players fell from grace and were forever marked the Black Sox

Outraged by the verdict and citing perceived perjury in some of the testimony, the trial judge set it aside and dismissed the case. Jackson’s attorney planned to appeal, citing the verdict as the first step in the player’s “ultimate return to organized baseball.”

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

- And, catch me Monday mornings on WLS-AM’s “The Steve Cochran Show” for a look at “This week in Chicago history”

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com