Forty-five years ago, Chicago prepared to welcome a visitor unlike any other.

Pope John Paul II (formerly known as Karol Wojtyla) was the first non-Italian leader of the Catholic Church in almost half a century. Born in Poland in 1920 but not ordained a priest until after World War II, the master of at least a dozen languages was elected Oct. 16, 1978 — making him among the youngest popes in history — amid much jubilation from Chicago’s Polish American community, which was the largest outside Warsaw.

“My parishioners are in seventh heaven,” Bishop Alfred L. Abramowicz told the Tribune at the time. “Pope John Paul II will be as lovable as John Paul I. He is an extremely holy man and is well-beloved by his people. He is a scholar, but he also has a great touch with the laboring man. During the war years he was a worker in a chemical factory in Krakow.”

There were three leaders of the Roman Catholic Church in 1978. Cardinal Albino Luciani of Venice was elected Aug. 26, 1978, following the death of Pope Paul VI. Yet the pontificate of Pope John Paul I (Luciani’s chosen name) would become among the shortest in the church’s history. He died of a heart attack in his sleep just 33 days after his election. Pope John Paul I’s successor would become among the church’s longest-serving pontiffs.

Rumors began to circulate in June 1979 that Pope John Paul II might travel to Chicago, which was then home to 2.4 million Catholics making it the largest archdiocese in North America. After his office confirmed the pontiff would speak before the United Nations General Assembly in New York City, word spread that he would return to Chicago in October 1979.

That’s right — it wasn’t the former Polish cardinal’s first time in the city. He led a group of bishops on a tour of the United States — that stopped in Chicago — in 1976.

Chicago history headlines

- The sweaty masks, the weird graphics: For generations of kids, Ben Cooper costumes meant Halloween

- The secret lives of Maurie and Flaurie, the Superdawg rooftop icons in Chicago

- Picketers shut down construction sites in 1969 in push for more Black union jobs

- The 2024 Chicago White Sox lost often — and in every fashion. Here’s a loss-by-loss look at their 41-121 season.

- Boodlers, bandits and notorious politicians: In Chicago, corruption is a source of both shame and perverse pride

Oct. 4, 1979: City rejoices — and so does Pope

On a cold, windy autumn night at 7 p.m., Pope John Paul II stepped off the Shepherd I jetliner to cheers from the more than 1,000 well-wishers and dignitaries that showed up at O’Hare International Airport to greet him. Escorted by Cardinal John Cody, the pontiff was serenaded by a group of 30 violin players, aged 3 to 15, before departing in a limousine.

When his motorcade made a brief detour from the Kennedy Expressway to travel along stretches of Nagle, Milwaukee and Lawrence avenues, an estimated 750,000 people — many who could barely see him — lined his path. Another 30,000 gathered outside his next stop.

The Pope delivered his first statement to the people of Chicago at Holy Name Cathedral: “How greatly I would like to meet each one of you personally, to visit you in your homes, to walk your streets so that I may better understand the richness of your personalities and the depth of your aspiration. May God uplift humanity in this great city of Chicago.”

Pope John Paul II speaks at Holy Name Cathedral in 1979, during his visit to Chicago. (Chicago Tribune historical photo)

As world-renowned opera singer Luciano Pavarotti sang “Ave Maria,” the pontiff sat in a chair at the center of the sanctuary’s altar. He “appeared slightly weary on his arrival in Chicago, the third city he visited during the day,” the Tribune reported.

He skipped a planned break to continue to St. Peter’s Church in the Loop where he was welcomed by a large assembly of Franciscan brothers and members of other Catholic orders.

Finally arriving at Cardinal Cody’s residence, 1555 N. State Parkway, at 10:15 p.m., Pope John Paul II took to a balcony to give those outside yet another sign — the last act from his first day in the city.

“Cupping (his hands) together, he placed them on his cheek, tilted his head in a sleeping motion, and smiling, reentered the mansion at 10:25 p.m.,” the Tribune reported.

Oct. 5, 1979: Pope, the city rise early

Friday began with shivering 40-degree temperatures “that numbed thousands of pilgrims who wore parkas and scarves and sipped coffee while they waited for a glimpse of the pontiff in the many places he toured,” Tribune reporters Monroe Anderson and William Gaines wrote.

Entering a motorcade shortly before 7:30 a.m., the pontiff was escorted throughout the city’s neighborhoods with tens of thousands greeting him with songs and cheers. He stopped to celebrate Mass in Spanish at Providence of God Church in Pilsen then in Polish at Five Holy Martyrs Church. Estimates of between 70,000 to 200,000 people crowded shoulder-to-shoulder outside each site.

Shortly after 2 p.m. the Pope took to the skies to see the city from a helicopter, cruising above the South Side and the lakefront before landing in Lincoln Park for a quick ride back to the cardinal’s residence.

Also on Oct. 5, 1979: Sermon by the shore

An overview of the crowds and main platform where the open-air Mass was celebrated at Grant Park during Pope John Paul II’s visit to Chicago on Oct. 5, 1979. (Ed Wagner Jr./Chicago Tribune)

For three hours, Grant Park became a church. A huge crowd — estimated at 1 million or more people — its congregation.

“Perhaps what didn’t happen at the Mass was as impressive as what did: The crowd did not, for the most part, become restless and rowdy, even though many — including children — had waited for four hours and longer,” Tribune reporter Michael Hirsley wrote a few days later.

Oct. 6, 1979: Pope departs

When the pontiff departed for Washington, D.C., he had been seen by some 2 million people throughout Chicago.

“If Chicago gushed unabashedly at its visitor from the Vatican, the 59-year-old leader of 600 million Catholics made Chicagoans feel it was a mutual friendship,” Hirsley wrote.

How many people really saw the Pope?

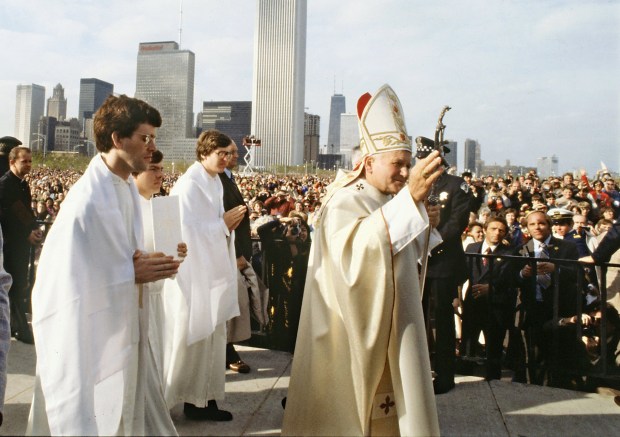

Pope John Paul II waves to the crowd during an open-air Mass at Chicago’s Grant Park on Oct. 5, 1979. (Bob Fila/Chicago Tribune)

Pope John Paul II’s nearly 3-hour Mass in Grant Park supposedly attracted 500,000 to 1.5 million people. One Tribune reporter wondered if the park could host a crowd nearly half as large as the city itself? Bill Currie set out to get answers.

Vintage Chicago Tribune: 5 largest crowd estimates in city history

Currie discovered the only way 1 million people could have attended the Mass was for some to be standing in — or on — Lake Michigan. He remains convinced that most crowd estimates are incorrect.

“I don’t think 1 million people (let alone 2 million) have ever gathered together in any one place in the world since time immemorial,” Currie said. “Prove it, I say.”

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com