It was the most infamous of all gangland slayings in America, and it savagely achieved its purpose — the elimination of the last challenge to Al Capone for the mantle of crime boss in Chicago.

The St. Valentine’s Day massacre shocked a city that had been numbed by Roaring ’20s gang warfare over control of illegal beer and whiskey distribution.

“These murders went out of the comprehension of a civilized city,” the Tribune editorialized. “The butchering of seven men by open daylight raises this question for Chicago: Is it helpless?”

In the following years, Capone and his henchmen were to become the targets of ambitious prosecutors.

Feb. 14, 1929: ‘Seven of Moran’s gang lined up against wall in own headquarters and killed by rivals’ machine guns’

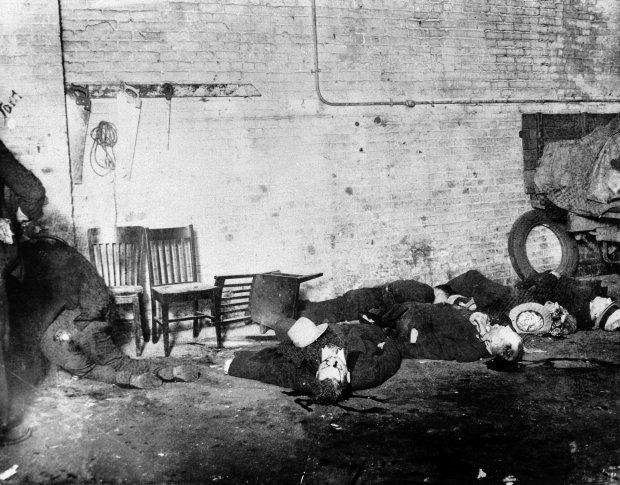

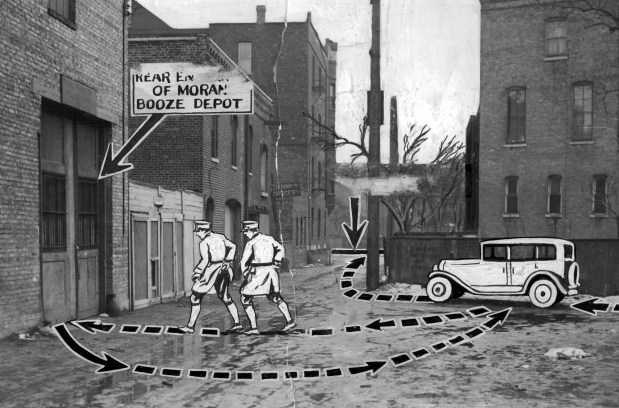

At about 10:30 a.m., four men burst into the SMC Cartage Co. garage at 2122 N. Clark St. Two of the men were dressed as police officers. The quartet presumably announced a raid and ordered the seven men inside the garage to line up against a wall. Then they opened fire — pumping the men with 90 bullets from submachine guns, shotguns and a revolver. Witnesses, alerted by the rat-a-tat staccato, watched as the assailants sped off in a black Cadillac touring car that looked like the kind police used, complete with siren, gong and rifle rack.

Police Capt. Thomas Condon, Sgt. Thomas J. Loftus and Detectives Joseph Connelley and John Devane of the old 36th District, who were assigned to investigate the savage homicides, turned in the following report about the victims:

- Peter “Goosy” Gusenberg, 434 Roscoe St., 40 years, American, no occupation.

- Frank “Hock” Gusenberg, 2130 Lincoln Park West, 36 years, American, no occupation, married.

- John May, 1249 W. Madison St., 35 years, American, mechanic, married.

- Adam Heyer, 2024 Farragut St. (Ave.), 40 years, American, accountant, married.

- Albert Weinshank, 6320 Kenmore Ave., 26 years, American, cleaner and dyer, married.

- Albert Kachellek, alias James Clark, 6036 Gunnison St., 40 years, German, no occupation, married.

- Reinhardt Schwimmer, 2100 Lincoln Park West, 29 years, American, optometrist, single.

Intended target: George ‘Bugs’ Moran

The press of the day described the bloody garage as “headquarters for booze-running operations of George ‘Bugs’ Moran’s crew of prohibition pirates and all-around racketeers.”

By 1929, Capone’s only real threat was Moran, who headed his own gang, and what was left of Dion O’Banion’s band of bootleggers. Moran had long despised Capone, and mockingly referred to him as “The Beast.”

Police investigating the massacre determined that Moran’s crew was set up by Capone’s hoodlums. Six of Moran’s henchmen — and an unfortunate optometrist who cavorted with criminals for thrills — had assembled in the garage to await what they had been led to believe would be a clandestine shipment of high-grade hooch.

Moran should have been the seventh victim, but he was late. He spotted the “police car” in front of his place as he came down the street and took off in the opposite direction.

After the shooting, the assailants dressed in police uniforms marched their two accomplices out at gunpoint, as though they were making an arrest. When they got to their bogus squad car, one of the “prisoners” in civilian clothes got behind the wheel as the other three climbed in, and they drove off.

Dr. Herman Bundesen, the city’s public health czar who was said to crave mentions in the press, offered photo ops at the scene. One of the most famous photos was captured by Jun Fujita, a Japanese American photojournalist who also captured heartbreaking images of those killed in the 1915 SS Eastland disaster and the 1919 race riots.

The mass murder all but wiped out Moran’s North Side gang, leaving the territory wide open for Capone. Moran died Feb. 25, 1957, of lung cancer while imprisoned at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Where was Capone?

Capone missed the excitement. Vacationing at his retreat at Palm Island, Florida, he had an alibi for his whereabouts and claimed to know nothing about the coldblooded killings. Few believed him, but no one ever went to jail for pulling a trigger in the Clark Street garage.

The Chicago Crime Commission named Capone “chief of gangland,” and the Tribune first referred to him as “public enemy No. 1″ in 1930. But by 1931, Capone had been arrested, convicted of five counts of tax evasion and sentenced to prison. He was released from Alcatraz in 1939 and died at his Florida home on Jan. 25, 1947.

Vaults inside a decrepit Chicago hotel were found embarrassingly empty in 1986, but the real riches of the legendary boss of the city’s organized crime syndicate were located more than 2,000 miles west in northern California, quietly occupying the homes of Capone’s four granddaughters — Veronica, Diane, Barbara and Theresa.

They decided to part with these pieces during a 2021 auction — nearly 75 years after the death of their grandfather.

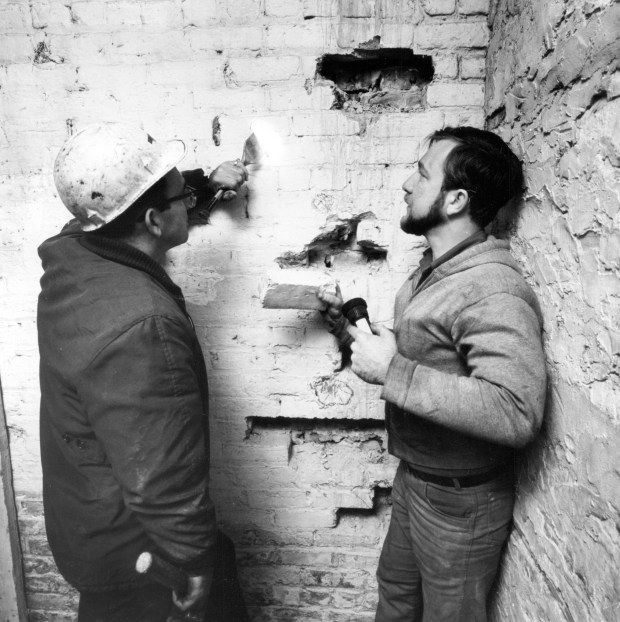

Nov. 1, 1967: ‘City wreckers to raze symbol of a dark era’

The old garage was ordered demolished shortly after it was used for the filming of a few scenes for the movie “The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre,” starring Jason Robards and George Segal.

“Known to tourists and local residents for the last 18 years only as Werner Storage, the obscure little garage at 2122 N. Clark St. has been a monument to the darkest days of Chicago’s gangland past,” the Tribune wrote.

The urban renewal department acquired the property after Werner moved out and lost no time in arranging to have it leveled.

“Generally we try to preserve buildings which are of historical significance to the city,” said George Stone, director of the Lincoln Park project. “But this is something we’d rather not remember.”

The fenced plot of land has a small parking lot and some trees.

A few artifacts from the Feb. 14, 1929, crime still exist — just not in Chicago

Up in Vancouver, British Columbia, an entrepreneur named George Patey read about the demolition of the garage and decided he would try to buy a piece, actually many pieces, of Chicago’s bloody past. Patey purchased a 7.5-foot-wide by 11-foot-high section of the bullet-riddled north wall. The price has never been disclosed, but the bricks, 417 of them, were numbered, packed in barrels and shipped to Canada. (Seven bricks were missing.)

The wall became a traveling exhibit, but the public decried it. A museum wouldn’t take it off Patey’s hands and eventually it was installed in the men’s room of the Banjo Palace, a Roaring ’20s-style saloon Patey owned. That place closed in the early 1990s and in 1996, Patey and his associate, E.W. “Bill” Eliason, tried to auction off the wall. The bidding, they said, would start at $200,000. They got a few offers but none serious. In 1998, they hooked up with an internet site that put individual bricks up for sale for $1,000. In five days, 68 were ordered, but the company went bust before any bricks were delivered.

Today, about 300 of the bricks are on permanent display at the Mob Museum in Las Vegas.

Two Thompson submachine guns linked to the crime will also be displayed at the Mob Museum on the 95th anniversary of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre. The firearms were discovered after a raid of Fred “Killer” Burke’s home in St. Joseph, Michigan, and forensics testing linked Burke and the guns to the crime. The guns are permanently housed at the sheriff’s office in Berrien County, Michigan

Want more vintage Chicago?

Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

And, catch me Monday mornings on WLS-AM’s “The Steve Cochran Show” for a look at “This week in Chicago history.”

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com.