In the early 1970s, Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein uncovered the connection between an attempted burglary of the Democratic National Committee headquarters and President Richard M. Nixon’s administration. Their work was aided by “Deep Throat,” their anonymous source nicknamed after a popular pornographic film but later revealed to be W. Mark Felt, Sr.

But, did you know, the Chicago Tribune also played a key role in the demise of Nixon’s presidency?

Fifty years ago this week, a small team of Tribune employees flew to Washington, D.C., and back in order to beat every other American newspaper to the punch — printing the entire transcript of the Watergate tapes, which were conversations recorded by Nixon in the White House.

They succeeded. The 246,000-word record was printed in a 44-page special section in the next day’s Tribune. This was, of course, before the widespread use of computers, and so hundreds of Tribune employees were involved in the effort.

For just 15 cents — the price of the newspaper back then — readers of the May 1, 1974, edition dug into Nixon’s expletive-laden discussions hours before they were sold to the public by the government’s printing office for $12.25.

The Tribune’s second punch to Nixon’s presidency was delivered on May 9, 1974. The Tribune’s Editorial Board, a longtime Republican stalwart, called for his resignation. With articles of impeachment looming, Nixon became the first — and only — U.S. president to resign.

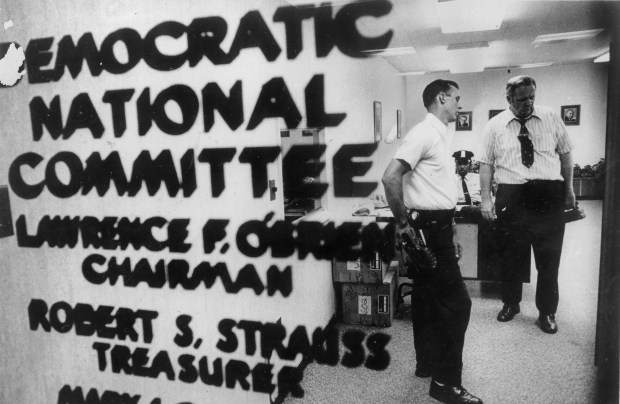

June 17, 1972: Watergate break-in suspect linked to G.O.P.

Early in the morning, Democratic Party offices in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C., were burglarized. Five men who were wiretapping the offices were arrested after a security guard noticed door latches covered with tape and called police. The five were linked to E. Howard Hunt, a former CIA agent who also had worked in the White House, and G. Gordon Liddy, an official at the Committee to Re-elect the President (known as CREEP).

Hunt’s wife, Dorothy, died in the crash of United Airlines Flight 553 near Chicago’s Midway International Airport seven months later. She was carrying $10,000 in cash on the flight, which news accounts reported was rumored to be Watergate hush money.

The Washington Post uncovered the attempted wiretapping and connected the scandal to Nixon’s administration. The White House initially dismissed the significance of the Watergate break-in, with press secretary Ron Ziegler calling it a “third-rate burglary.” But behind the scenes, the Nixon administration was working to obstruct the FBI’s investigation.

July 16, 1973: Bombshell — Nixon bugged his own offices

Alexander P. Butterfield, formerly the deputy assistant to the president, testified before the Senate Watergate Committee that all conversations in the president’s Oval Office and his office in the old Executive Office Building next door to the White House were recorded on tape.

Both the Senate and special Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox subpoenaed the tapes, but the White House refused to release them, citing executive privilege.

Four months later, Nixon denied knowledge of the Watergate break-in and cover-up and told reporters in Orlando, Florida, “I am not a crook.”

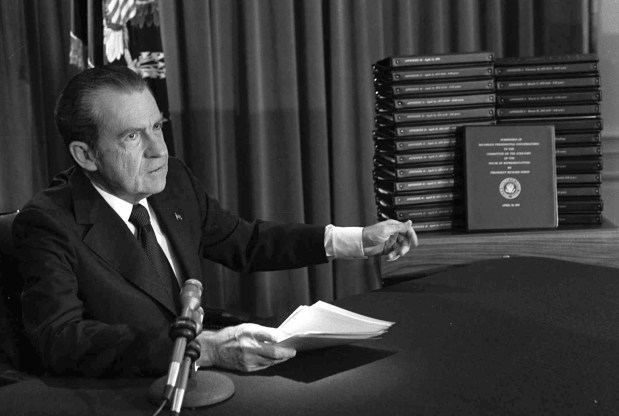

April 29, 1974: Nixon vows to release tape data — ‘They tell it all’

In a 35-minute nationally televised speech, Nixon told the American people he would reluctantly release transcripts of all conversations he had on the Watergate scandal from Sept. 15, 1972, to April 27, 1973 — more than 1,200 estimated pages.

He conceded that the tapes contained “uninhibited conversations” and “brutal candor,” including remarks that would be seized upon by his political opponents to embarrass him and make him the subject of ridicule. Nixon insisted, however, that the tapes showed his innocence in the Watergate cover-up.

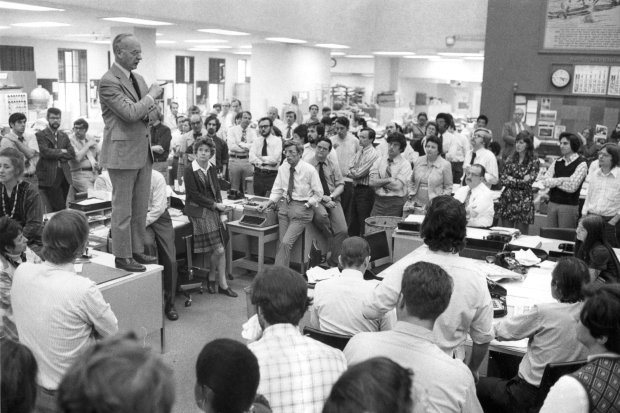

April 30, 1974: How Tribune got the transcripts

Shortly after Nixon’s announcement, the Tribune assembled a team of editorial and production crew members that flew to Washington, D.C., at 5 a.m. on the company’s plane.

Frank Starr, the Tribune’s Washington bureau chief, obtained two copies of the transcripts — each consisting of 50 bound volumes totaling 1,308 pages — and delivered them to the team.

“We spent five minutes looking at the documents on the ground, and then we took off,” Tribune Assistant News Editor Richard Leslie said. “We started working before we were airborne.”

Leslie said the plane returned to Meigs Field instead of Midway to save a few minutes’ driving time and the copies were rushed to Tribune Tower where the volumes were separated, copied and then distributed among the many editors and printers required to handle them.

“We chopped the bindings with a paper cutter and made three more copies,” Leslie said. “Then we went to work on them.”

No changes or edits were made to any of the transcripts.

May 1, 1974: Nixon tape transcript published in 44-page section

The report, one of the largest short-deadline efforts in Tribune history, was published in its entirety just hours after the Tribune obtained it.

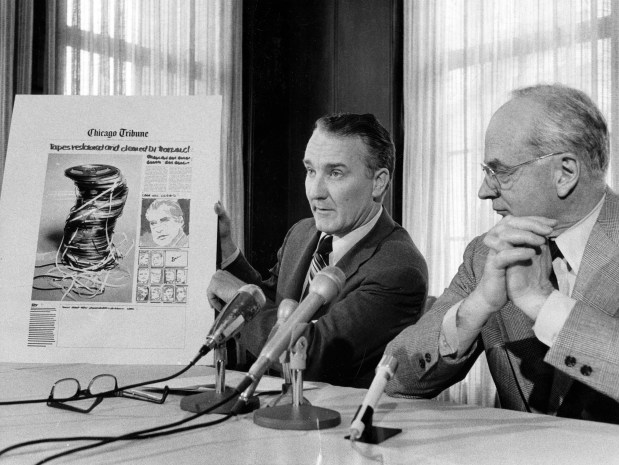

May 9, 1974: ‘Listen, Mr. Nixon’

Nixon visited a supportive Tribune Editorial Board on Sept. 17, 1970 — less than four years later it published a three-part editorial calling for him to either resign or be removed from office.

“We saw the public man in his first administration, and we were impressed. Now in about 300,000 words we have seen the private man, and we are appalled,” the editorial began.

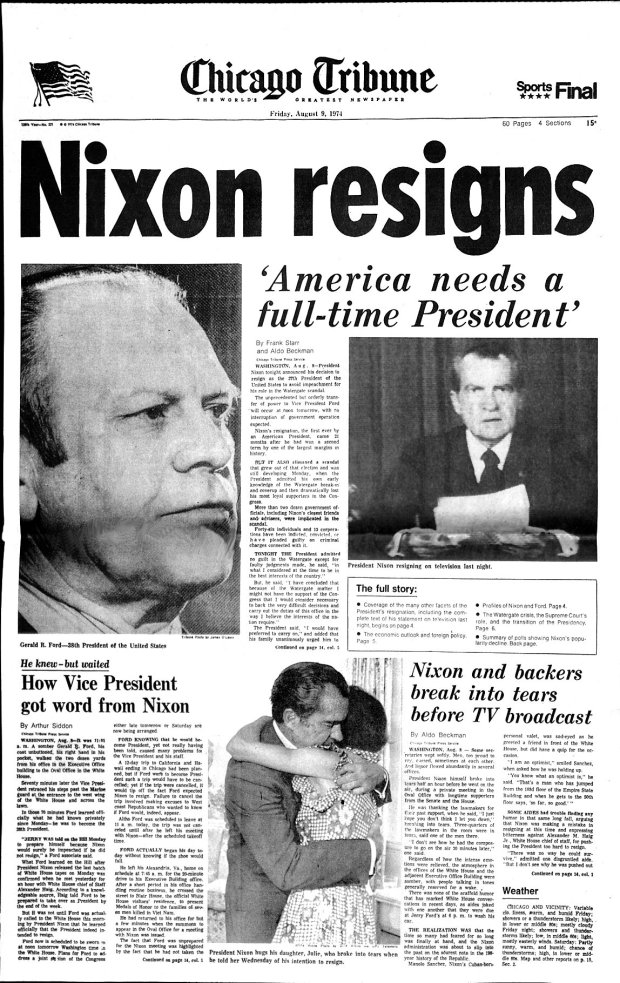

Aug. 8, 1974: ‘I shall resign’

Nixon became the first-ever U.S. president to announce his resignation and also admitted his own early knowledge of the Watergate break-in and cover-up during a nationally televised broadcast. His admission came 21 months after Nixon won a second term by one of the largest margins in history.

The Tribune Editorial Board wrote of the occasion: “Our feelings toward Mr. Nixon must be of sorrow rather than anger, and of mercy rather than vengeance. His weaknesses are more of blind ambition and poor judgment than deliberate contempt for the law. He has paid the heaviest price a man in public office can pay.”

Aug. 9, 1974: ‘Our long national nightmare is over’

Precisely two hours before Nixon’s resignation became effective, his green and white helicopter lifted off the south lawn of the White House and disappeared over the Jefferson Memorial.

Gerald Ford was sworn in as the 38th president at 11:05 a.m. CST, although he legally became president 40 minutes earlier when Nixon’s one-line letter of resignation was delivered to the office of Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

More than 30 government and Republican officials were convicted in the scandal. Nixon was pardoned by Ford on Sept. 8, 1974.

Want more vintage Chicago?

- Become a Tribune subscriber: It’s just $12 for a 1-year digital subscription

- Follow us on Instagram: @vintagetribune

- And, catch me Monday mornings on WLS-AM’s “The Steve Cochran Show” for a look at “This week in Chicago history”

Thanks for reading!

Join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Have an idea for Vintage Chicago Tribune? Share it with Ron Grossman and Marianne Mather at rgrossman@chicagotribune.com and mmather@chicagotribune.com