“Dog Man: The Musical,” which is playing at the Studebaker Theatre on Michigan Avenue though Feb. 25, is a gateway drug for children into musical theater. I learned this personally, studying my daughter, still coming off a “Mean Girls” movie musical high. One minute she’s insisting on more Olivia Rodrigo in the car, the next she wants “Don’t Rain on My Parade.” Again and again. The Barbra Streisand no less, not the Lea Michele.

Not that I should be surprised.

If you have no idea who Dog Man is: Dog Man is the kind of generational line in the sand that appears every few years that, with time, proves again how wrong parents can be. Jazz, Vietnam, Hip Hop, “On the Road,” Dog Man. I remember very clearly my grandfather trying to understand my sensibilities and listening to a Steve Martin album only to decide, with no irony at all, “This guy is a total … jerk.” Dog Man, though, shifts the generational divide from boundary-testing teenage years into early grade school.

I resisted Dog Man for a while.

Not because I had anything against author Dav Pilkey and his earlier “Captain Underpants” book series (a common target for the humorless and misguided who haunt library board meetings). Not because I’m opposed to comic books (and “Dog Man” books, like the “Captain Underpants” books, are undoubtedly comics, winkingly sold as “graphic novels”). Not because I have a problem even with caustic, scatological kiddie nihilism.

But because … because …

“Why?” my daughter would ask.

I couldn’t say, and the dumbest of reasons: I hadn’t read a “Dog Man” book, and hadn’t recognized yet that “Dog Man” books, like “Dog Man: The Musical,” are transcendent kid’s culture, yet on the down low. “Why?” in fact, is a mantra of the books, as well as the musical, which stops for a minute as a young cat (L’il Petey) questions an older cat (Petey), over and over: “Why?” The replies are insufficient, the adult Petey stammers, which just leads to more whys. It’s a solid lesson in refusing to accept a company line.

So, lesson No. 1: Musical theater is weird fun.

Lesson no. 2: Question authority (particularly parents).

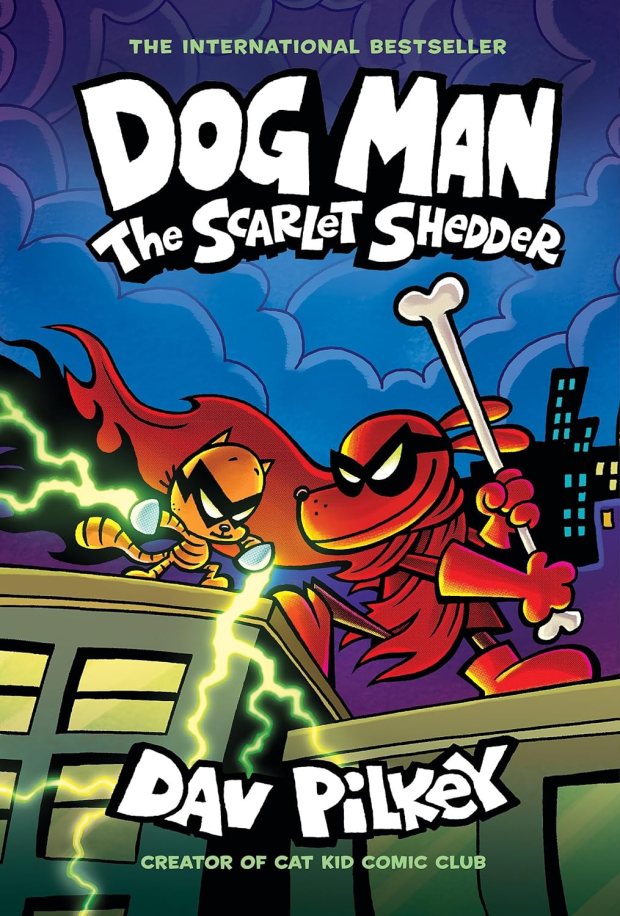

Pilkey’s creation is so alive with off-handed, never-underlined thoughts on how to create and stay curious, I wasn’t surprised to spot this headline in the trade publication School Library Journal: “Is there a looming Dog-Man crisis?” The author — noting the arrival of 12th “Dog Man” book, “Dog Man: The Scarlet Shredder,” on March 19 — feared the rise of school-library-targeted legislation and bureaucratic book-buying committees could result in libraries without the new “Dog Man” book, which is unthinkable if you are of a certain age. But also, the author writes, a civic lessons for kids. (Indeed, there are stories of school libraries holding raffles for the honor of checking out a new “Dog Man” book first.)

Lesson no. 3: Adults are scared of what they don’t understand.

For instance, when I asked my daughter what she thought of “Dog Man: The Musical,” one of the first things she said was that, until now, she hadn’t thought that boy characters could be played by women or vice versa. She had assumed 80-HD (or, slyly, “ADHD”), a “Dog Man” robot character, had to be portrayed by a male. She also assumed L’il Petey had to be played by a male. But in one scene, L’il Petey (played by L.R. Davidson with a chipper joy that makes Kristin Chenoweth look like Darth Vader) climbs into a cockpit of 80-HD — destroying gender assumptions, if you’re in first grade.

Lesson no. 4: Gender-blind casting isn’t so hard.

Moreover, my daughter noted several limitations in adapting a book for stage. Namely, the Flip-o-Ramas, a favorite gag in all of the Dog Man books — basically, flipping the drawings on two pages back and forth quickly, to create an illusion of movement — aren’t doable. The show, though, is irreverent enough to come to a dead stop for a moment and try to recreate the magic of a flip book for an audience of children and their parents, and when the actors slowly realize that experiencing live theater is different from the action of sitting down and reading a printed book, they shrug and move on.

That’s one of the best lessons of Dog Man in general.

“Dog Man: The Scarlet Shedder” by author and illustrator Dav Pilkey (Graphix, March 2024).

Lesson no. 5: Embrace creative limitations.

The main aesthetic of the Dog Man books, and the musical — and presumably, the recently-announced animated feature film, coming next year from DreamWorks — is raw and happy. The art looks lifted from a seven-year old, complete with stray marks and scratched out words. The stage show continues that handmade spirit with its backdrops and props — 80-HD is clearly a large exercise ball fitted with long accordion pipe hoses. Here and there the dialogue is spotted with malaprops, a nice approximation of the book series’ fondness for misspellings so creative that even kids suspect something’s wrong.

If you’re wondering by now what “Dog Man” is about, well, that’s also an approximation, of narrative. It’s also a way of describing a child coming up a coherent story on the spot. Fans of the long-running “That’s Weird, Grandma” shows at the Neo-Futurists Theater in Andersonville — known for squeezing the strange thoughts of its audience of children into inspired lunacy — would get the gist: A cop and his dog are blown up by a bomb, so surgeons fuse the dog’s head to the cop’s body and create Dog Man, who fights an evil cat (Petey) who wants to create evil clones. Also, there is a cyborg fish. Also, buildings that come to life and attack everyone. Also, somewhere in there are notes of empathy, abandonment and acceptance — all evident without once being conveyed as lessons.

The adventures of Dog Man are actually tales told by a pair of fifth-grade boys named George and Harold. Sincere, heartwarming lessons are anathema. No, no: Poops, farts and snots — that’s the true heart of Dog Man stories, bundled into punny titles such as “Fetch-22” and “For Whom the Ball Rolls” and “Twenty Thousand Fleas Under the Sea.” The secret is that the physical books, the musical (adapted from “A Tale of Two Kitties”) — it all looks doable, if you’re unrestrained by things like good taste and common sense.

My point is, I’ve made my peace with Dog Man.

He’s a good boy.

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com