The occasional boom of a bass drum punctuates the Mass at St. Francis Borgia Deaf Center on the Northwest Side, signaling particularly important moments during the liturgical service, which is celebrated each Sunday in American Sign Language and spoken English.

While many Catholic churches ring small bells for auditory cues, the deep vibrations of the drum beat ripple through the wooden pews of this Dunning neighborhood chapel, a tactile prompt for its predominantly deaf and hard of hearing congregation.

“We hit that drum to kind of signify, look at what’s going on, pay attention,” said the Rev. Joseph Mulcrone, director of the Archdiocese of Chicago’s Catholic Office of the Deaf. “It’s a place where they can worship in their language and in their way.”

Across the Chicago area, houses of worship for Deaf communities provide distinctive means of prayer and spiritual formation, with heightened focus on sight and touch as opposed to the various aural elements that lace so many traditional religious rites and ceremonies.

Services at Congregation Bene Shalom-Hebrew Association of the Deaf and Hearing in Skokie — the first synagogue in the United States designed to assist the Deaf community — are trilingual, translated from spoken English and Hebrew to American Sign Language.

Ephphatha Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Deaf “celebrates Jesus by ministering the Word of the Lord through the language of sign,” according to its mission statement. The predominantly Black church on the South Side will commemorate its 60th anniversary in January.

For three decades, an Archdiocese of Chicago-supported Ministry Formation Program has been training Deaf Catholics to become lay leaders in church ministry. The program celebrated its 30th anniversary during Mass at St. Francis Borgia Deaf Center in mid-September. It’s the only training of its kind in the nation and graduates of the three-year certification program go on to lead or create various ministries for the Deaf including Bible studies and youth education, as well as outreach to nursing homes and hospitals.

On a recent Sunday at the chapel at St. Francis Borgia Deaf Center, Mulcrone used his entire body and facial expressions to help explain the Gospel passage while giving a homily in American Sign Language and voice.

The priest closed his eyes and shook his head to convey the sadness of a rich man, who could not part with his many earthly possessions when asked to do so by Christ in order to receive eternal life. Mulcrone’s brow furrowed to illustrate the frustration of attempting to thread a camel through the eye of a needle, which Jesus describes in scripture as an easier task than the wealthy entering the kingdom of heaven.

“Think about this: At the end of our lives, we have to go and stand before God,” Mulcrone said and signed. “Now I know some Deaf have asked me, ‘If I go, is God going to sign?’”

Some in the crowd of 100 to 150 worshippers started to laugh.

“God invented sign language. You can’t fool God saying, ‘Well, you don’t know sign language.’ No way,” the priest continued, shaking his head and wagging his finger, eliciting more laughs from the pews. “So we’re all going to have to stand there in front of God. God isn’t going to look at us and say … how big was your house? How fancy were your clothes? No. God’s going to ask, ‘Did you love one another?’”

After Mass, parishioners gathered in the hall for coffee and often silent though lively conversations, marked by a flurry of hands quickly weaving signs. The church bulletin featured news items about local health services for the Deaf, information about finding sign language interpreters for Catholic funerals, and a class for adults who are deaf and want to learn about the sacrament of confirmation.

In the hall, Antoinette Angel said she often grappled with her faith as the child of hearing parents who attended a regular church. She recalled that her grandmother — who didn’t know sign language but had a hard of hearing sister — made sure she learned the Lord’s Prayer and how to recite the rosary.

“The hearing Mass is so hard,” she said. “I don’t know what they teach. … I was struggling. I felt like something’s wrong with me. Am I missing out? Everyone hears and I don’t.”

She and her husband Francisco Angel traveled to the chapel with their three children from their home in Hammond. The family is quadrilingual: Francisco Angel was born in Mexico and used Mexican Sign Language and Spanish growing up. Their kids, ages 7 to 17, can hear but their first language was American Sign Language because it was taught to them by their parents.

While the drive to services can be an hour or longer with traffic, Antoinette Angel said it’s easier to maintain and grow her faith with a supportive church community that’s accessible, rather than trying to do so alone.

“I feel connected here,” she said.

Joseph Delulio of Schaumburg remarked that if he had to attend a hearing church, he would be lost.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” he said through an interpreter. “I’d be missing everything.”

At St. Francis Borgia Deaf Center, Delulio said he feels fully embraced culturally and spiritually.

“I love sign language. It’s beautiful,” he added. “It’s better than the hearing world. Deaf is better.”

Hands in prayer

The focal point of a Jewish synagogue’s sanctuary is the ark, an often ornate cabinet that enshrines the Torah scrolls, sacred hand-written texts of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

The doors of the ark at Congregation Bene Shalom in Skokie are decorated with a bronze sculpture of two hands in prayer.

“Because we speak with hands,” said Rabbi Charlene Brooks. “We pray with mind, body and soul, is how I feel. But also with our hands.”

The Reform Jewish congregation was founded in 1972 by a handful of deaf families. Today, the majority of members are hearing, but the synagogue continues to have all services interpreted from English and Hebrew into American Sign Language, Brooks said.

During a service on the holiday Yom Kippur, known as the Day of Atonement, the Torah scrolls were removed from the ark and held by several members. One was 37-year-old Paul Donets of Gurnee, who is deaf and has been attending the synagogue with his parents since he was 8.

“Attending Congregation Bene Shalom is not like attending another temple,” Donets said in an email. “The charisma of opening the ark hits you with something spiritual, that when you attend another temple you do not feel it. It feels like a safe haven and a place where you are welcomed. Congregation Bene Shalom feels like you are closer to God and you feel you can speak with God one on one.”

The temple was on the precipice of closing due to lack of funding during the height of the COVID pandemic, but was revived by donations. Then in 2022, founding Rabbi Douglas Goldhamer died after 50 years of serving the congregation.

Now Congregation Bene Shalom has only a few members who are deaf, Donets said, adding “we hope to bring back the Deaf population … with a new rabbi now in lead.”

“The current members now are hearing but are friendly and do learn signs,” he said. “They even sign to the songs while saying prayer with assistance of the rabbi and the interpreter. It is really a Deaf-friendly temple.”

Brooks has been a member for about 30 years and was the temple’s longtime cantor before becoming its rabbi in 2022. Although no one in her family was deaf, the temple was only a block from their home and she felt embraced by its warm, close-knit spiritual community.

Brooks said she and her daughter learned sign language over the years and took ASL classes. The rabbi also works with the ASL interpreter to capture the meaning of prayers and readings, as opposed to line-by-line or rote translations.

“ASL is a visual language. It’s like pictures,” Brooks said. “You can’t just speak the words, you actually have to embody them. It has to reflect on your face. It has to reflect in your arms and your body and your hands. It’s quite beautiful.”

For example, the Shema, a central prayer in Judaism, is translated from Hebrew as “Hear, O Israel,” she said.

Brooks said at Congregation Bene Shalom, they sign this as “pay attention Israel.”

“What we’re saying is pay attention. Understand. Intuit. Get the meaning,” she said. “Not to physically hear it. … When you’re using sign language to interpret, you’re all about the deeper meaning.”

Brooks recalled that years ago, her daughter had a difficult time falling asleep for a period during early childhood. Rabbi Goldhamer had recommended the little girl recite the Shema each night at bedtime.

Her daughter would grow too tired to speak the prayer and would instead sign it as she fell asleep, Brooks said.

“And she would just do it instinctively. Because it was the same thing as saying it aloud,” Brooks recounted. “So sometimes things are easier to say in sign language, because you’re not using too many words. You’re just conveying the intention.”

‘Be opened’

About a half-dozen women sipped coffee and snacked on cookies during a recent mid-week Bible study at Ephphatha Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Deaf in the Chatham neighborhood.

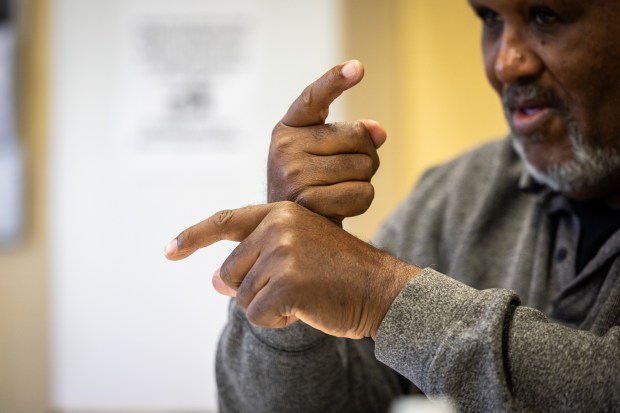

The Rev. Prentice D. Marsh began an oral quiz in spoken English and sign language on their Bible readings, teasing that he didn’t want to catch anyone sneaking answers on their cellphones.

“My phone is clean,” one member insisted, laughing.

They correctly answered a series of questions about Adam and Eve and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Jacob and his sons. Joseph’s multi-colored coat and dream prophecies. Moses and the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt.

The pastor asked the group to name some of the plagues that afflicted Egypt. One woman signed “flies.” Another woman signed “frogs.”

Then Marsh pointed out that all the plagues were still written on a chalkboard behind them after their last session. The Bible study burst into laughter.

“Y’all remember. Y’all are studying. That’s wonderful,” the pastor said and signed, adding that he’s proud of them.

The church’s name Ephphatha comes from the New Testament book of Mark’s account of Jesus healing a deaf man: Then, looking up to heaven, He sighed and said to him “Ephphatha,” that is, “Be opened.” Immediately his ears were opened, and the impediment of his tongue was loosed, and he spoke plainly.”

The first official worship service was conducted at Ephphatha in January 1965. It’s believed to be the only Chicago church built and designed specifically for a deaf congregation, with a floor sloped at a 30-degree angle to promote visibility for all the pews and a glass wall in back so anyone standing in the overflow area can still see.

Marsh said he never turns his back to the congregation; one of his members recently attended another church and found some aspects of the service to be odd.

“She said ‘pastor, it was so strange. In the hearing church the pastor turned his back to us. He faces the altar,’” he recalled her saying.

Marsh also doesn’t use a microphone.

“If I want to talk louder, I just sign bigger,” he said.

The church features a Gospel choir where members sign and sing. Marsh said they play the music extremely loud so the choir can feel the sound’s reverberations to learn their songs and hymns.

“You hear these kids driving around the city and they’ve got the music really loud and your house windows vibrate? That’s how loud it is,” Marsh, who is not deaf or hard of hearing, said with a laugh. “It used to drive me nuts when it was really loud. But now I’m used to it.”

Marsh has served at Ephphatha for 40 years. While attending seminary, he was directed toward Deaf ministry because he spoke with a stammer.

“Because I stuttered, the president of the school thought I wouldn’t work well in a hearing church,” the pastor recalled, laughing again. “He was full of stuff.”

But Marsh soon found a calling to serve the Deaf. While attending a clergy training program in the late 1970s at Gallaudet University, a Washington, D.C., school for deaf and hard of hearing students, Marsh met his future wife, who was studying to be an ASL interpreter.

“My wife, she signs circles around me. She signs more on the college level,” he said. “But I never wanted to be an interpreter. I’m a pastor. And I’m going to talk (and sign) like you talk.”

After Bible study, a few of the members lingered to chat or pour one last cup of coffee, including Debra Diggs of Chicago, who explained that it would be much more difficult to try to understand a Bible class or worship at a hearing church.

A nearby sign decorating the wall behind her displayed a Bible verse from the Book of Psalms: Your word is like a lamp that guides my steps, a light that shows the path I should take.

“This is a Deaf church and everything is very clear for us to understand God’s word,” Diggs said. “I don’t miss my class for nobody. I don’t miss coming to church unless it’s an emergency. It’s a blessing to be here. It’s a blessing to walk into God’s house.”

Sense of home

In American Sign Language, folks are often given a “name sign” or nickname to identify them quickly, without having to spell out each letter of a full name.

Sometimes the name sign describes a striking physical characteristic or personality trait.

The parishioners at St. Francis Borgia Deaf Center have a sign for Mulcrone, whom they call Father Joe: First they sign “priest,” swiping a forefinger and thumb across their neck, signifying a clerical collar; then they sign J, the first letter of his name.

Three decades ago, Mulcrone started the Ministry Formation Program to teach Deaf Catholics to serve lay ministry roles in their native language. It began as a largely local project but now sessions are held online — with an annual in-person retreat — so participants come from all over the country.

Since its inception, 65 to 70 people have completed the program, which is supported by the Archdiocese of Chicago, National Catholic Office of the Deaf and the International Catholic Deaf Association.

“What we’re doing is really planting seeds for the future, so … even if there’s no formal ministry in their diocese, deaf people themselves are educated and empowered,” said Ian Robertson, director of the program. “What it does is provide hope for the future in terms of the involvement of deaf people in the church.”

Sometimes graduates go on to lead Bible studies or care ministries for nursing home and hospital patients; some serve as extraordinary ministers of the Eucharist, lay people who distribute Holy Communion to the faithful who are often hospitalized or homebound.

They might go into a nursing home or retirement community where there’s only one or two residents who are deaf, which can be lonely when others don’t understand the same language, Robertson noted. While these ministries might only reach a handful of individuals, those people — and their spiritual lives — are important, he added.

For the first two years of the program, courses cover topics such as pastoral skills in the Deaf community, moral decision making, sacraments and evangelization. Several classes focus heavily on scripture, so participants can understand sacred texts well enough to translate them into ASL, Robertson said.

“It takes some work and skill to take the written word — or what we call the frozen text — and put that into the visual language of American Sign Language,” he said. “You’re communicating not just the word itself but the emotions. I’ve seen some days where there will be a parable in the Gospel where Jesus heals somebody and you can see the physical, emotional response that this person is healed. … You’re actually healed, you’re communicating the joy of that, the surprise of that. It can be much more expressive.”

During the third year, participants create a pastoral project and present it at an in-person gathering.

Minette Sternke of Champaign completed the program in 2008 and now coordinates a deaf and hard of hearing ministry at her parish, St. Patrick Catholic Church in Urbana.

Sternke also sometimes interprets Mass.

“This allows the local Deaf to feel more included in parish celebrations,” she said in an email.

When Sternke was still a student in the program, she began taking Holy Communion to homebound Deaf Catholics, including one man who was deaf and blind.

“It was a great privilege to be able to take the Holy Sacrament to him and to also share some stories about what was happening in the Deaf world,” she recalled.

Sternke added that the program has helped “connect me with my Deaf faith roots.”

“Wherever I go, if I can find a Catholic church, I feel as if I’m home. Ministry Formation Program taught me that many Deaf people do not have that particular feeling when they go to Mass,” she said. “It’s hard to feel at home when you have no idea why people are kneeling, standing, sitting, etc., and what is going on during the service. One of my main goals then became helping other Deaf people feel that sense of ‘home.’”

eleventis@chicagotribune.com